The majority of families in Detroit face the risk of death, injury, illness and loss of their children’s mental capacity every day because of hazards in their homes. Based upon highly detailed analyses of homes, it is clear that homes are causing burns, falls, asthma, allergies and lead poisoning.

A detailed survey of Detroit homes, conducted by the Center for Urban Studies at Wayne State University, found that over 62 percent of nearly 500 randomly selected homes have at least one high risk hazard that is likely to lead to poor health outcomes. [1] Of these, 4.2 percent of the homes have three or more hazards in these high risk categories. These dangerous housing conditions, combined with high unemployment and continued crime, are driving people to leave the city in droves.

Recent estimates show Detroit is continuing to lose residents at fast clip, about 1,155 residents[2] a month.

The City is working hard on unemployment (and the improvement of the economy as a whole is helping) and on increased and smarter policing. But on housing for existing residents, far more needs to be done, not just by the City, but by the State and the Federal Government.

To stop this decline and avoid the health consequences of dangerous homes, Detroit and policy makers need to focus far more efforts on providing safe and healthy homes.

As of July 2014, Detroit had a total of 252,173 occupied housing units.[3] However, our best estimates—very generous–are that only around 500 a year are being substantially improved to make them healthy and safe places to live, while just over 800 new housing units were built last year.[4] This is an estimated total of 1,300 homes being produced per year. At this pace, it will be many decades before vast majority of Detroit’s residents can live in safe and healthy homes.

What is a reasonable goal for creating healthy homes for Detroit’s children? A modest goal would be to house all of Detroit’s 193,150 children[5] in safe housing within 10 years. Approximately 3 percent of households (or around 6,000 children) already reside in housing built later than 1980[6] and, in most cases, this is relatively safe housing.[7] A total of about 79,400 households with children live in pre-1980 housing, and we estimate 38 percent are in houses that have only minor hazards[8]. That means 49,259 households are living in homes where one or more major hazard puts them at risk every day. Having nearly 50,000 households plagued with one or more hazards is unacceptable, which is why the families residing in these homes need either new or rehabilitated housing, and they need it soon.

Within 10 years—a short time in the policy world—policy makers should be able to address these needs. To avoid deaths, injuries, illness and loss of mental capacity caused by home environments, Detroit needs at least 4,900 new or rehabilitated homes a year. That is 3.8 times the number we estimate that is being produced now. And this is only the number necessary to protect families with children, not other vulnerable populations such as the elderly.

We need to massively expand renovation and construction, specifically, in these ways:

- First, concentrate on housing with children, the most vulnerable among us, for rehabilitation;

- Let’s give families with children a priority to relocate to subsidized housing that has been built after 1980 or that has been re-built and remediated, including lead abatement.

- Make homes healthy through small investments. Some homes can be made healthy for an investment of substantially less than $5,000. The Green & Healthy Homes Initiative Detroit-Wayne County has shown this can be done. We need to do more of this.

- Work to improve and remove hazards from current houses, rather than new construction. In cases where the abatement of lead hazards is necessary, the work can cost an average of $20,000,[9] still a fraction of the cost of a new construction.

- Use code enforcement to force rental owners to substantially improve homes. Progress is being made here, but the number of code inspectors, cut sharply in the midst of Detroit’s fiscal difficulties, needs to be expanded substantially.

- Ensure all new construction in Detroit includes affordable units.

- Increasingly the private sector is rehabilitating homes in Detroit. These rehabilitations should pass all standards, especially including the removal of asbestos and lead-based paint. Currently, private sector rehabilitations do not have to pass all standards among governmental and lending organizations that control the sale and rehabilitation of many of these homes.

- Leverage local and state resources, ranging from public entities to non-profit and for-profit organizations, to develop a robust rehabilitation program. Mayor Duggan has made a good start here with his zero interest loan program, but many families cannot meet the income and other requirements required by this program. We need grant programs to assist these low income homeowners.

- Many thousands of families are living in homes that have black mold and other major damage from the August, 2014 floods across Detroit and other communities in Southeast Michigan. FEMA and other agencies need to invest in these homes to protect people from major health problems.

Healthy Homes Risk Assessments

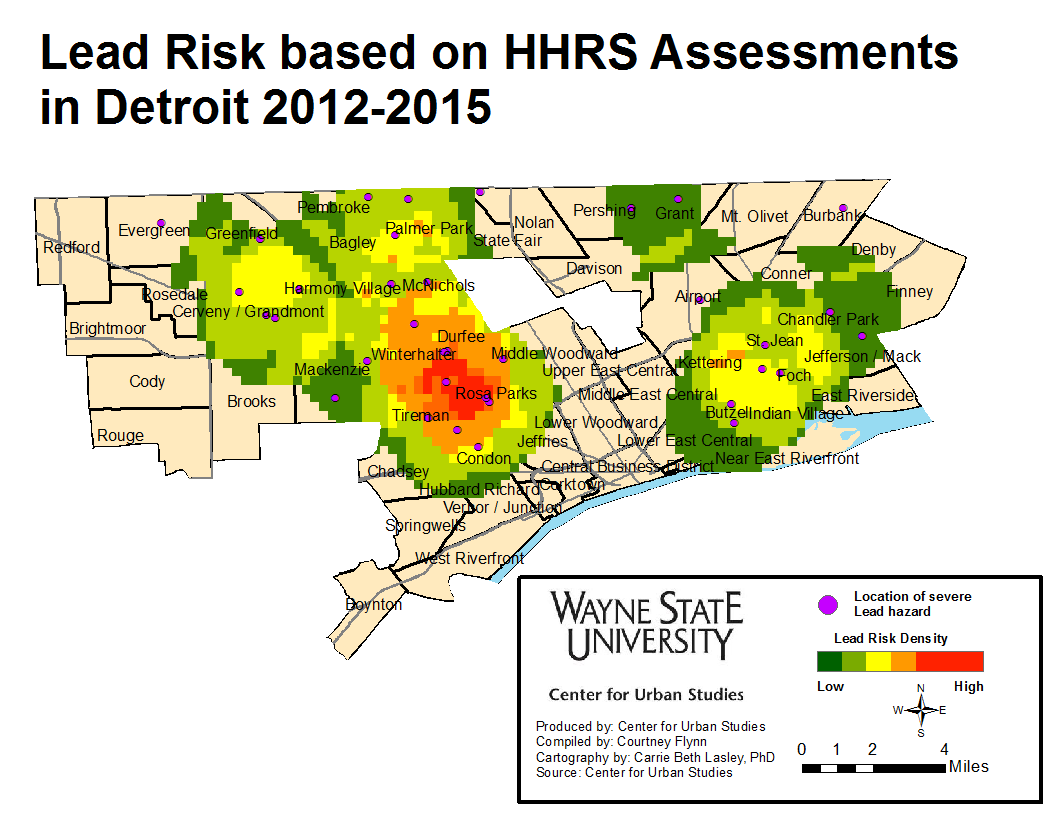

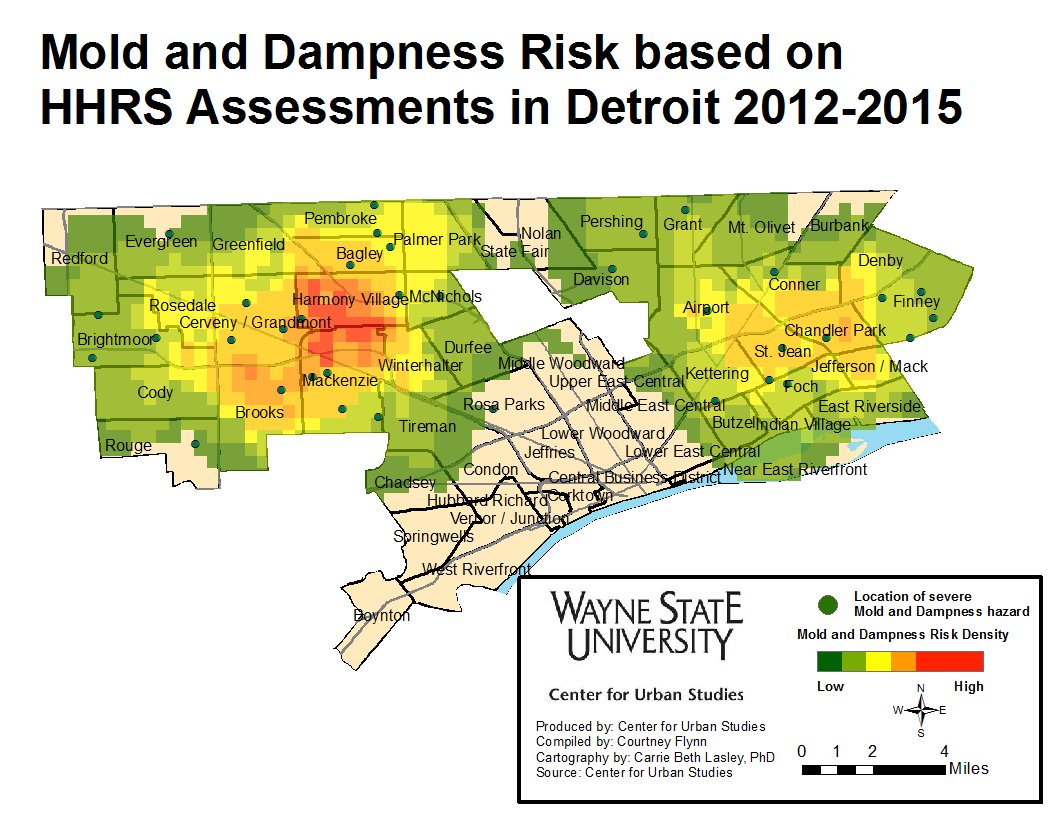

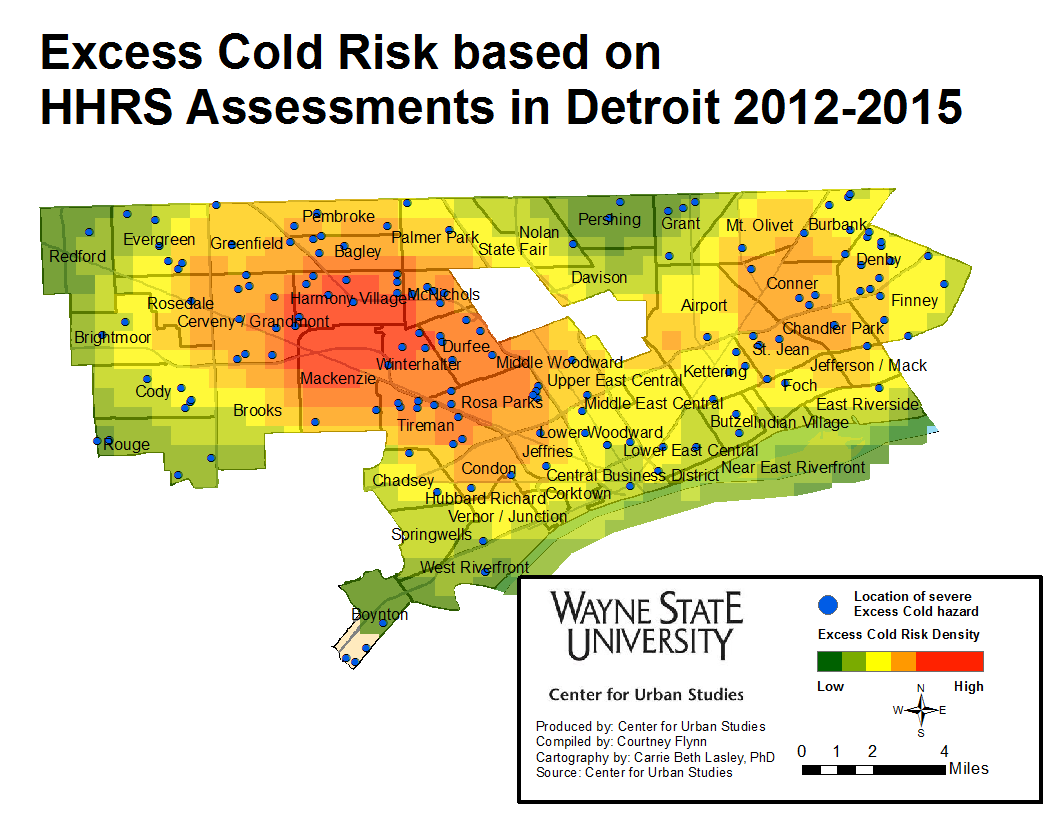

These maps below are based on a random sample of 500 homes spread broadly across Detroit. At each house assessors completed a Healthy Homes Rating System assessment that examined 29 potential hazards. This rating system is a HUD-endorsed rating instrument that assesses both the probability of injury and extent of injury from a hazard. Three of the most frequently occurring and severe hazards were excess cold, mold and dampness and lead paint. The following three maps portray of the areas of Detroit that had the highest levels of hazards.

[1] This data is collected using the Healthy Homes Rating System (http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/healthy_homes/hhrs). According to this system, a “high-risk” hazard is identified by a rating of A, B or C on a scale of A-J, A being highest likelihood of serious injury or death and J being minimal risk.

[2] This calculation is based on the April 1, 2010 estimate based on the Census and a 2014 estimate from SEMCOG, broken down into a monthly estimate by simple division across the months.

[3] SEMCOG Community Profile, City of Detroit (http://www.semcog.org/Data/Apps/comprof/people.cfm?cpid=5)

[4] At best only several hundred houses a year are being improved to systematically reduce health hazards. It is important to note, however, that about 806 new housing units were constructed in Detroit last year.

[5]U.S. Census Bureau, Demographic and Housing Estimates, 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Detroit city, Michigan (http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_11_5YR_DP04)

[6] U.S. Census Bureau, Households and Families, 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Detroit city, Michigan (http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_13_1YR_S1101&prodType=table), U.S. Census Bureau, Households and Families, 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Detroit city, Michigan (http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_13_1YR_DP04&prodType=table) This is probably an underestimate as we were unable to obtain of precise occupancy data for post-1980 housing.

[7] It is also important to know that lead paint was banned for use in residences in 1978 and taken off the shelves in 1980.

[8] This estimate is based on the results from the Healthy Homes Rating System being conducted in Detroit.

[9] This cost may include the replacement of all windows within the home as this is a major source of lead.