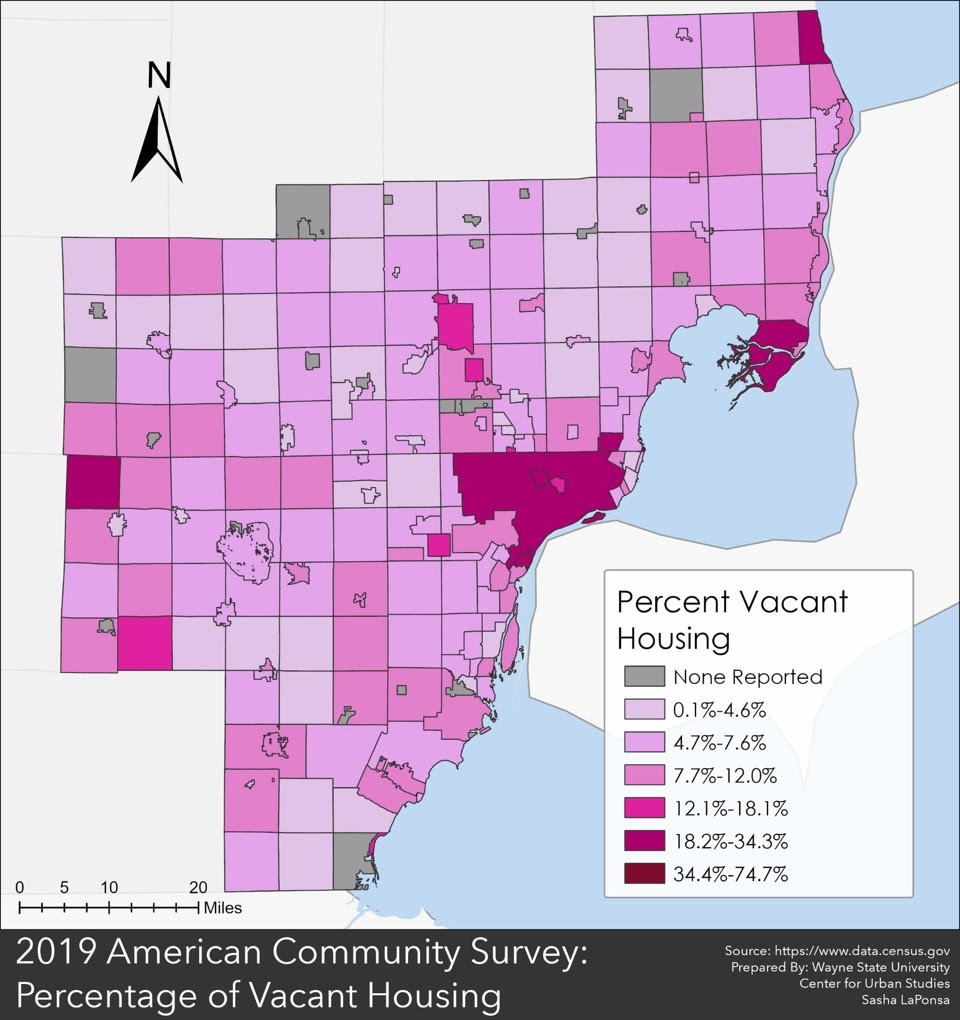

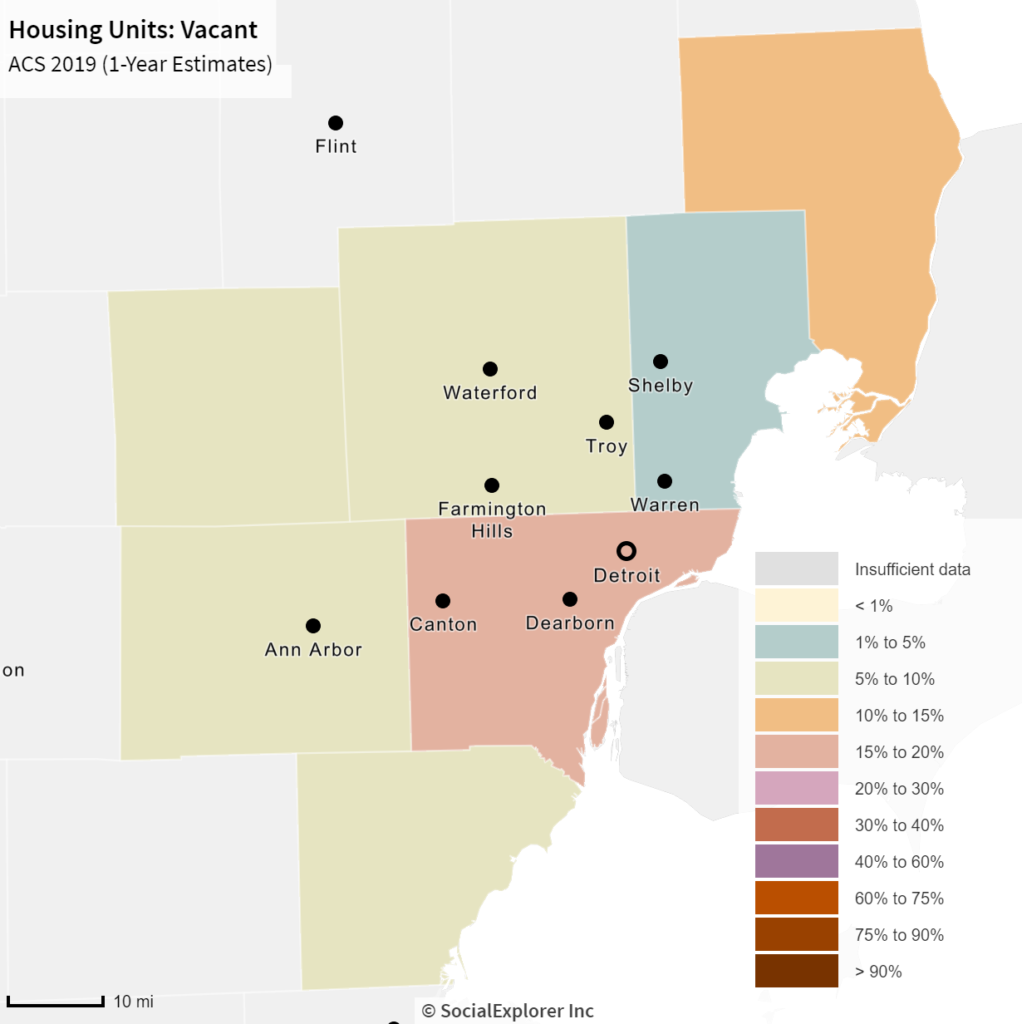

In 2019, Highland Park had the highest vacancy rate in Southeastern Michigan at 34 percent, according to the American Community Survey; the vacancy rate is the percentage of all available units in a rental property, such as a hotel or apartment complex, that are vacant or unoccupied. Clay Township (St. Clair County) had the second highest vacancy rate at 30 percent and Detroit had the third highest rate at 27percent. There were only seven communities in the region with vacancy rates at or above 20 percent; of those communities four were Detroit or an inner-ring suburb (Highland Park, River Rouge and Eastpointe) and the remaining three were outer-ring suburbs (Clay, Burtchville and Lyndon townships). While there were a handful of outer-ring suburbs with high vacancy rates, those with the lowest vacancy rates were all outer-ring suburbs. Orchard Lake Village had the lowest vacancy rate in 2019 at 1.4 percent, followed by Clarkston at 1.6 percent and Plymouth and Augusta townships at 1.8 percent. The inner-ring suburb with the lowest vacancy rate was Southfield Township at 4.1 percent, followed by Allen Park at 4.9 percent.

In knowing that the Detroit inner-ring suburbs had among the highest vacancy rates in the region, it is not surprising that Wayne County had the highest vacancy rate at the county-level at 15.5 percent. However, St. Clair County had the second highest vacancy rate at 12 percent; St. Clair County is home to the community with the highest vacancy rate (Clay Township). When breaking down the type of vacancies that makeup each county’s overall percentage though Wayne County did not rank the highest amongst any of the categories. The breakdown of vacancy types-housings units for sale, housings units for rent and “other” (described below)-is only available at the county level. So, while we cannot fully understand the specifics of vacancy rates at the municipal level, the county data does give us some insight.

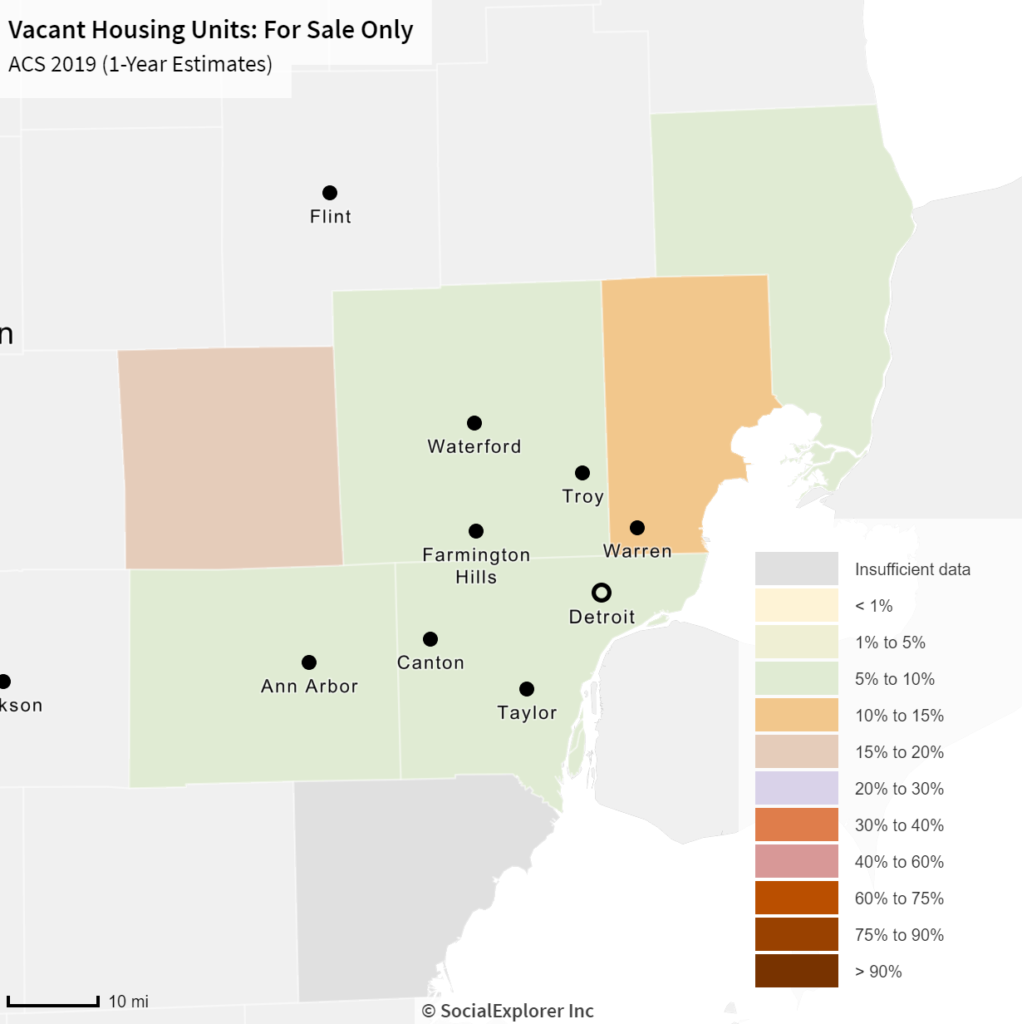

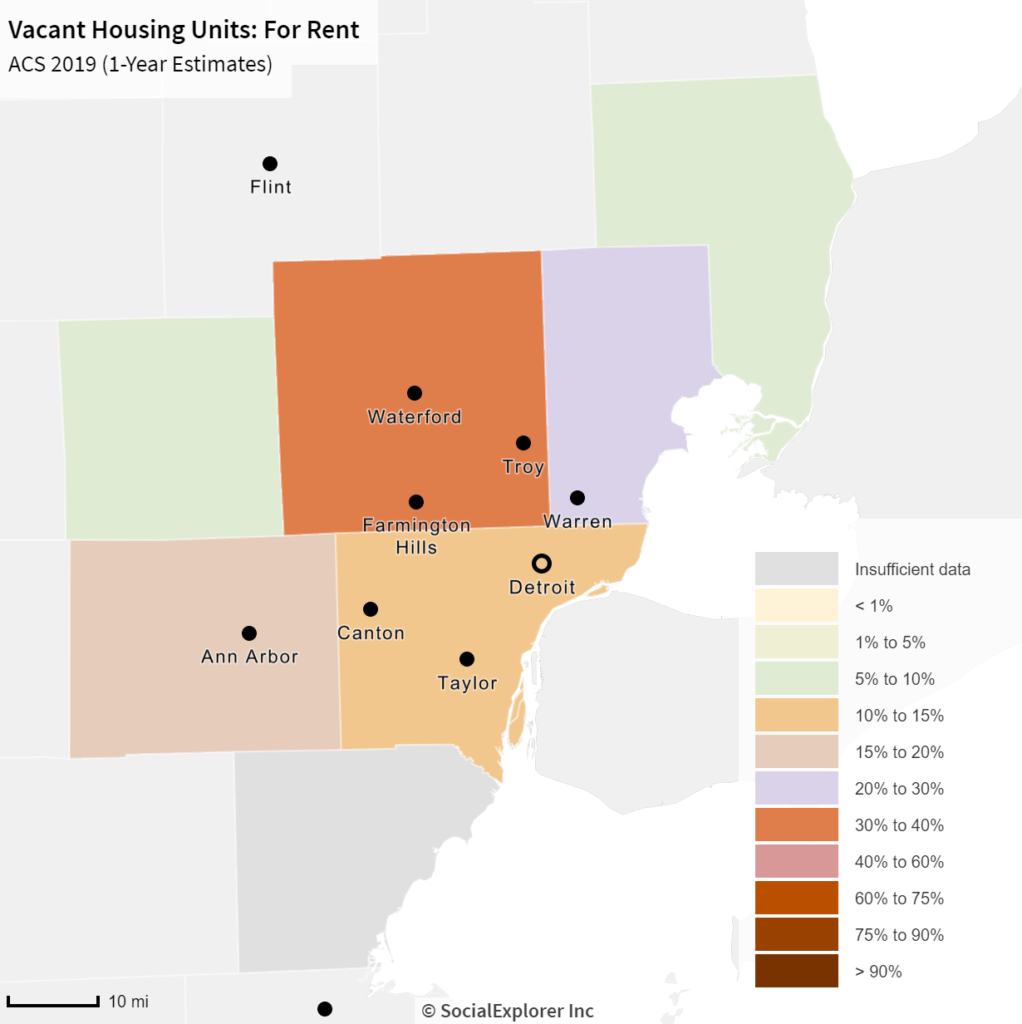

According to the data, Livingston County had the highest percentage of vacant homes for sale at 18 percent, followed by Macomb County at 14 percent and then Wayne County at 10 percent. For rental vacancies, Oakland County had the highest percentage at 31 percent and Macomb County at 26 percent; Wayne County had an 11 percent vacancy rate for rentals. Overall we see that rental units tend to have higher vacancy rates than homes for sale; the rental vacancy rate may grow even higher in areas such as Detroit where demand for rentals is down just as new apartment buildings are opening, according to the Detroit Free Press.

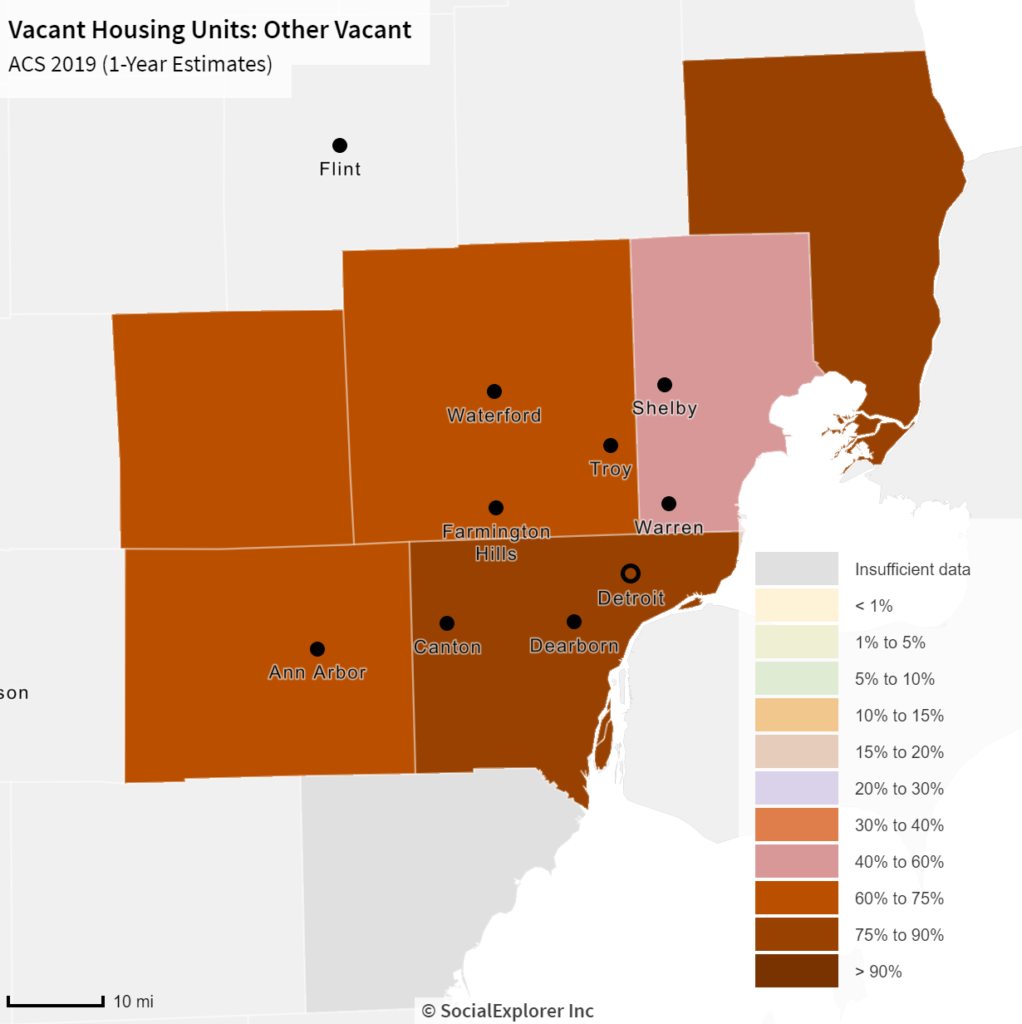

A property is labeled as “other” vacant by the U.S. Census Bureau when it does not fit into one of the categories discussed above. According to the U.S. Census Bureau “other” properties are typically vacant because the owner does not want to rent or sell it; it is being used for storage; the elderly homeowners are living in a nursing home; it’s in an estate settlement; it is being repaired or renovated or it is in foreclosure. According to the data at the County level, St. Clair County had the highest percentage of “other” vacant properties (as described above) at 88 percent, followed by Wayne County at 79 percent. Macomb County had the lowest percentage at 60 percent. This data was only available at the county level.

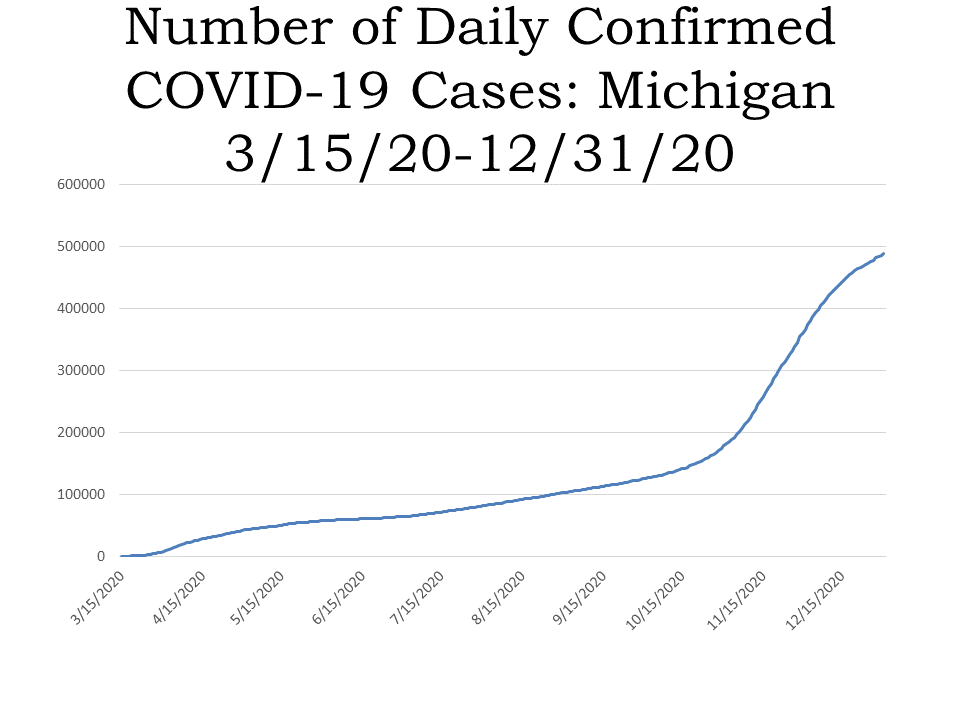

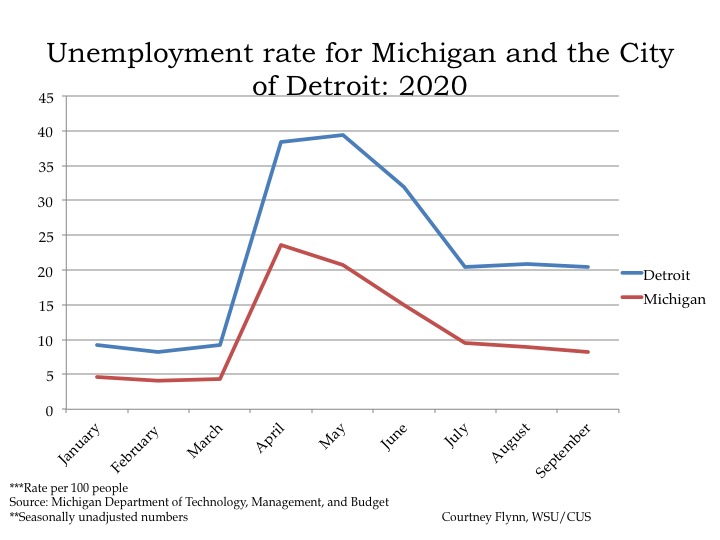

While the breakdown of vacancy rates is only available at the County level it does shed some light on why certain communities may have some of the highest vacancy rates. For example, we know that communities such as Highland Park and Detroit have higher vacancy rates due houses being abandoned and people leaving those cities for outer-ring suburbs. Furthermore, according to Next Gen City, the highest vacancy rates are in areas that have the highest population of black residents; Detroit and Highland Park have the highest black populations in the State of Michigan. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the economy it will interesting to see how vacancy rates change in the future.