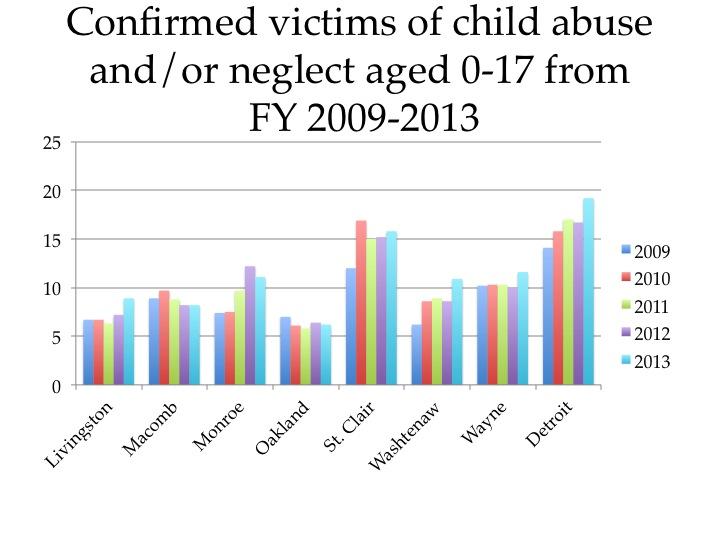

From 2009 to 2013, St. Clair County consistently had the highest rate of confirmed victims of child abuse and/or neglect in the seven county region, according to the Michigan League for Public Policy and Kids Count (these organizations obtained their data from the Michigan Department of Human Services). However, for four of those five years, Detroit’s rate of confirmed child abuse/neglect victims far exceeded that of St. Clair County.

All rates discussed in this post are per 1,000 children ages 0-17, unless otherwise noted. These numbers reflect an unduplicated count of children in a given fiscal year where the alleged abuse or neglect was confirmed after an investigation, according to the Michigan Department of Human Services.

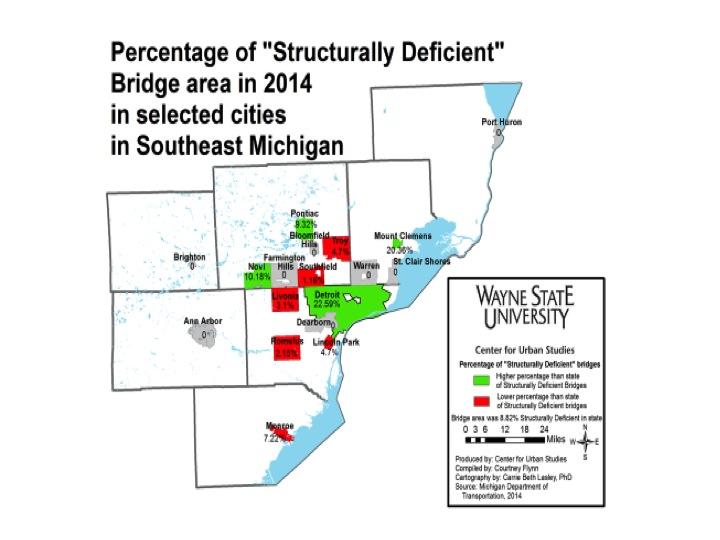

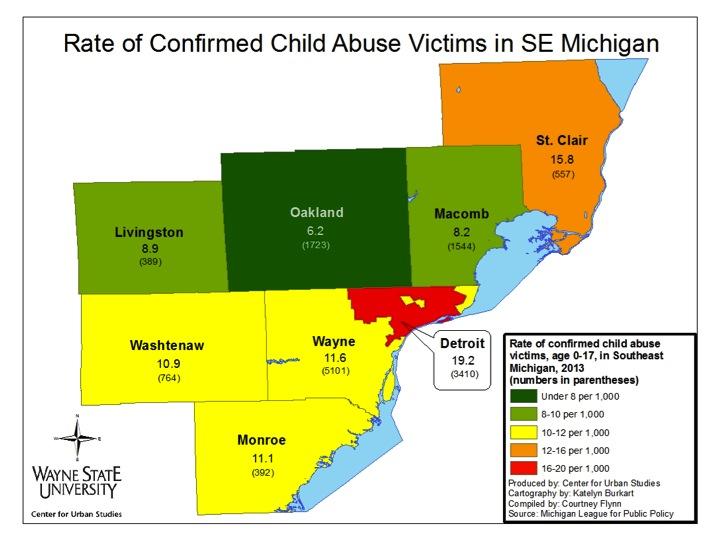

The map above shows the rate and number of confirmed victims of child abuse/neglect for the region in fiscal year 2013. Detroit, which is the only Michigan city with such information available through the data source, had a higher rate than the counties (19.2) in 2013. This rate of 19.2 confirmed victims of abuse and/or neglect per 1,000 children ages 0-17 was equivalent to 3,410 total cases.

As already noted, St. Clair County had the highest child abuse/neglect victim rate of the counties in the region in 2013 at 15.8; this was 557 confirmed victims.

In 2013, Oakland County had the lowest child abuse/neglect victim rate in the region. The rate was 6.2, which equaled 1,723 confirmed victims.

The rate of confirmed child abuse/neglect victims for the State of Michigan in 2013 was 14.9 per 1,000 children.

With the exception of 2010, from 2009 to 2013, Detroit had higher rates of confirmed child abuse/neglect victims than the counties in the region. In 2010, St. Clair County had the highest rate at 16.9 per 1,000 children; Detroit’s rate was 15.8 per 1,000 children at that time. Additionally, Detroit experienced its largest rate increase between 2012 and 2013; the rate increased from 16.7 to 19.2 per 1,000 children. Between 2012 and 2013, Macomb, Oakland, and Monroe counties were the only ones that did not experience a rate increase. Between 2012 and 2013, Macomb County’s rate remained the same at 8.2, while Monroe County’s rate decreased from 12.2 to 11.1 and Oakland County’s rate decreased from 6.4 to 6.2.

Macomb and Oakland counties were the only counties in the region that experienced rate decreases between 2009 and 2013.

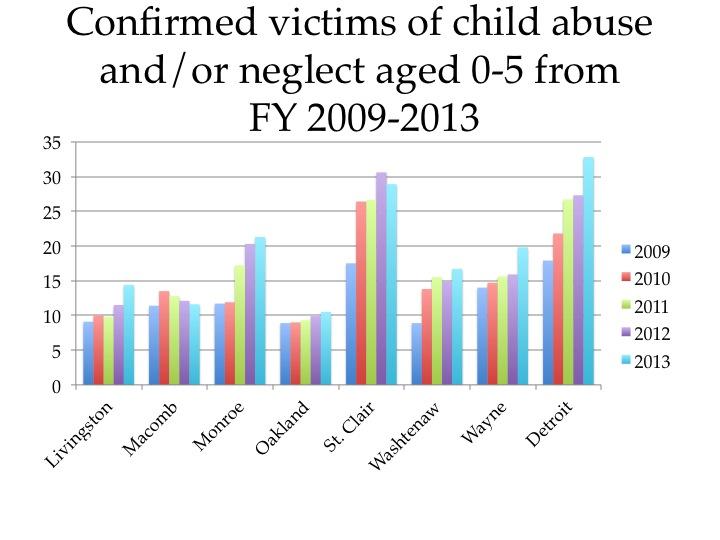

In the above chart, we look at the rate of confirmed child abuse/neglect victims for children between the ages of 0-5 in the region. Again, we see that Detroit and St. Clair County had the highest rates. In 2013, Detroit’s rate was 32.8, while St. Clair County’s was 28.9 per 1,000 children. In 2009, 2010, and 2012, St. Clair’s rates (17.5, 26.4, 30.6, respectively) were higher than Detroit’s (17, 21.8, 27.3, respectively).

For all the years examined, Oakland County had the lowest confirmed child abuse/neglect rates in the region for children ages 0-5. In 2009, its rate was 8.9 and by 2013, its rate had increased to 10.5. Overall, there was a general trend of rate increases across the region. Detroit had the largest rate increase between 2009 and 2013; its rate increased by 15.8 in that five-year time frame.

Although Macomb County’s rate increased by 2.1 between 2009 and 2010, it is the only county in the region that experienced a consistent downward trend in the confirmed child abuse/neglect victim rate between 2010 and 2013, leaving it only .2 points higher than its 2009 rate. Of the counties examined, this was the closest any county in 2013 was to its rate in 2009.per 1,000 children in 2010. But since 2010 the rate has decreased each year.