Rising inflation is hitting people all over the metropolitan area. For example, food banks are experiencing increased use, according to local media outlets. In the Metro-Detroit area major food banks include Gleaners Community Bank and Forgotten Harvest; these organizations not only supply food to those in need via their mobile food pantries and sponsored distribution events; they also provide food to soup kitchens, other organizations’ food pantries and other programs. According to MichiganRadio.org, in March of 2022 Gleaners Community Food Bank had about 13,000 visits to its mobile food pantries; the average number of visits in the six months prior to that was about 9,000. Feeding America West Michigan experienced a 34 percent increase in visits between February and March of 2022, according to the April 2022 Michigan Radio. A recent Model D article states that the Capuchin Soup Kitchen experienced a 25 percent increase in visits in the last year. Additionally, the same Model D Media article reports that Forgotten Harvest recorded a 30 percent increase month-to-month between April, May and June of this year. According to the article, Forgotten Harvest served 16,000 individuals in the month of June— 10,400 more than in the same month last year.

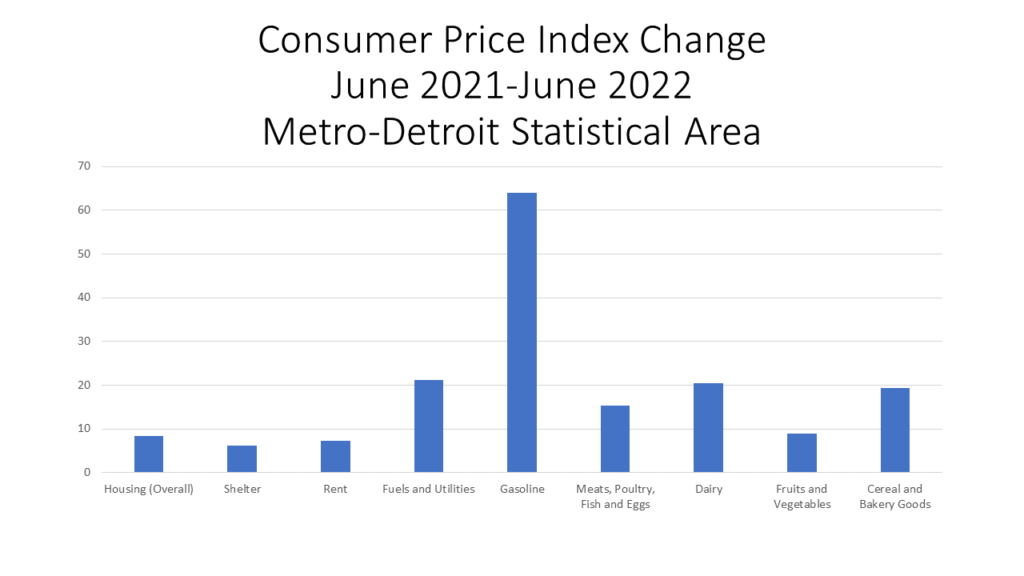

The charts below show just what inflation means to the average person. For example, in the first chart below, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of meat, poultry, fish and eggs has increased by 8.4 percent in the Metro-Detroit area between July of 2021 and July of 2022. Dairy has increased by about 20 percent in that time frame and cereal and bakery goods have increased by about 19.3 percent. As we know, not only are food prices increasing but so is the cost of housing, utilities and gas. Gasoline has experienced the largest consumer price index increase in the last year at 63.9 percent.

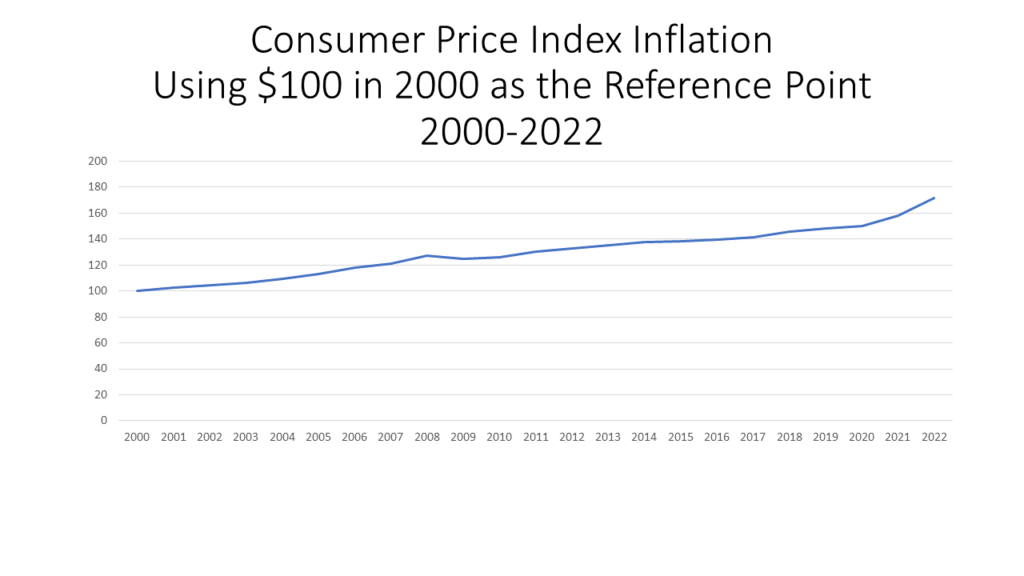

Another way to view inflation is to understand how the value of a dollar, or $100, has changed. The chart below uses $100 in June of 2000 as a reference point to show inflation over the last 22 years. So, for example, $171.46 today would be the same as $100 in June of 2000. In other words, the purchasing power of the dollar has continually decreased, except between 2008 and 2009. Between 2020 and 2022 the purchasing power of the dollar has had the largest decrease since 2000. Between 2020 and 2022 there was a $21.52 difference in the power of the dollar. What you could buy for $149.74 in 2020 increased to $171.46. And again, these dollar figures are comparable to what $100 would be worth in 2000.

Additional allocations to food banks will certainly help with the increased use in food pantries, but the State Budget funding was a one-time allocation and the duration of the increased use in food pantries is unknown. The state, and federal government, though are working toward food security through other avenues as well. For example, about 1.3 million people from about 700,000 households in Michigan receive federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits through the state’s Food Assistance Program. Since the COVID pandemic began, all household have received the maximum benefits allowed for their size, and this practice continues. Following the May 2021 SNAP benefit amount increase, households of the following sizes are receiving the corresponding max benefit amount:

•

·One Person: $250

·Two Persons: $459

·Three Persons: $658

·Four Persons: $835

·Five Persons: $992

·Six Persons: $1,190

·Seven Persons: $1,316

·Eight Persons: $1,504

In August, households receiving SNAP benefits had an additional $95 added to their Bridge card to help further combat the affect inflation is having on food costs. How long this will last is unknown as federal approval of the increased SNAP benefits is necessary every month.

Schools are also working to create greater food security for students but either adopting a universal free lunch policy for all students, or at least sending free and reduced lunch applications to all households in the district. According to the Kids Count Data Center, 715,000 of Michigan public K-12 students qualified for free or reduced lunches’ income bracket in 2021. During that time though, all students—nationwide—received free lunches as part of a federal program implemented in the height of the COVID pandemic. This school year though, that policy does not exist and Michigan does not have a universal school lunch policy. Detroit Public Schools implemented one though, as have some others throughout the story. For the many districts that do not have such a policy, free and reduced lunch applications are being sent to all homes so eligible students can receive the service. For reduced meals, breakfast is $0.30 and lunch is $0.40. Income eligibility information can be found here.

We know that food banks are meeting, and serving, just some of the thousands upon thousands of individuals being impacted by the affects of inflation. However, long-term assistance to such food banks remains unknown, as direct long-term funding from state entities isn’t certain, and with economic concerns growing, donations may decrease. Food pantries serve a vital role in our community, as do programs such as SNAP and the Free and Reduced School Lunch Program. Food insecurity is an issue hundreds of thousands Americans face daily and long-term strategies to create food security need stronger framework and better funding.

To find a food bank in Michigan click here.