Water rates have grown for most ratepayers across Southeastern Michigan for years, whether it be from the increases passed down to wholesale customers by the Great Lakes Water Authority and/or the increases passed down from the municipalities to their citizens. These increases, in short, are based on the servicing of debt and the cost of delivering clean and safe drinking to residents across the region. As Michigan’s infrastructure continues to age, ratepayers and government entities will have to foot the bill to ensure that the necessary replacement and improvements continue.

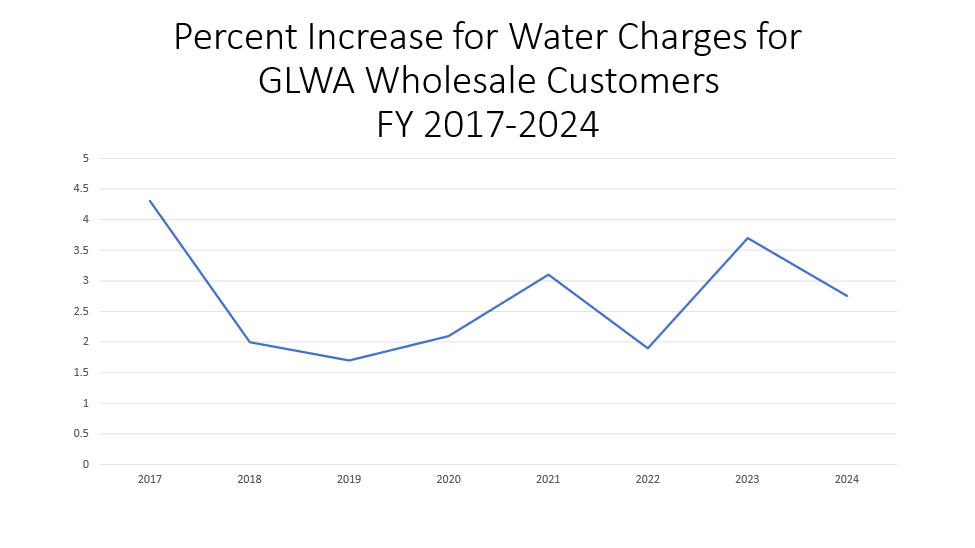

In Southeastern Michigan there are 86 communities that are part of the Great Lakes Water Authority (GLWA) system. This system officially went online in 2016 after approval by Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties in 2014 with the promise to provide improved services to the former Detroit Water and Sewer Department (DWSD) customers. The approval of the GLWA meant that all former DWSD wholesale customers (who are local government entities) became customers of the GLWA. The exception was the City of Detroit, which continued to own and operate its own system. At the time of the creation of this regional authority there was a promise that annual overall budget increases would be 4 percent or less. As the GLWA passes on more water and sewer (we are not exploring sewer system charges in this post) increases for one local city or townships could go above 4 percent. However, according to the annual budgets produced by the GLWA, water system increases for suburban wholesale customers have not exceeded 4 percent, except in Fiscal Year 2017.

As the chart below shows, Fiscal Year 2017 had an overall increase of 4.3 percent. Fiscal Year 2018 had an increase of 2 percent. Fiscal Year 2019 had the lowest increase for water charges for suburban wholesale member partners at 1.7 percent. For Fiscal Year 2024 the increase is 2.75 percent.

These percentage increases are passed down to the communities who purchase wholesale water from the GLWA, but water rate increases for these communities’ ratepayers are not always in line with the increases passed down by the GLWA. Rather, municipalities typically add their own operating costs on top of GLWA’s charges, according to the GLWA’s explanation of charges. These rates are known as the retail rates and are ultimately what customers pay.

At the same time, the GLWA may pass down standard rate increases to their wholesale customers as costs per million cubic feet (mcf) based on who the customer is. These rates vary according to whether the wholesale customer has the ability to store water, how many ratepayers there are in a community and the distance and elevation of the community from where the water is being transported from. There is no standard commodity rate for individual communities. It is important to note that the GLWA charges at an mcf rate while local communities charge at centrum cubic feet (ccf) rate[1]. While this does not allow for a simple comparison between the two rates (wholesale v ratepayer), there is an even deeper explanation on why there is not an apples-to-apples comparison between wholesale and ratepayer rates.

As noted, retail water rates are set by elected boards, often at the recommendation of their finance and public works departments. These recommended rates are based on the wholesale prices communities pay to GLWA, the investment needed to maintain and update the city or township’s infrastructure, debt service and their staffing levels. Water rates can also be lower but fees such as a “water meter fee,” which is a fixed cost on the bill, can account for a “lower” water rate (in appearance only). Also, the elected bodies may choose not to pass on increased costs from the GLWA or for infrastructure investment.

Because of how retail water rates are set, which vary from how wholesale rates are set, there is not an easy comparison between these either. GLWA’s wholesale rates are based on the fixed monthly charge and the wholesale commodity rate charged to communities. These charges are determined by the amount of water usage by each community as well as the distance and elevation of that community from the water source (it takes more energy to pump water uphill or long distances than it does to pump it to areas near the source). The local water storage capacity of each member community can affect the rates they pay because when a community can store water they don’t need to purchase it at higher, or “peak,” rates.

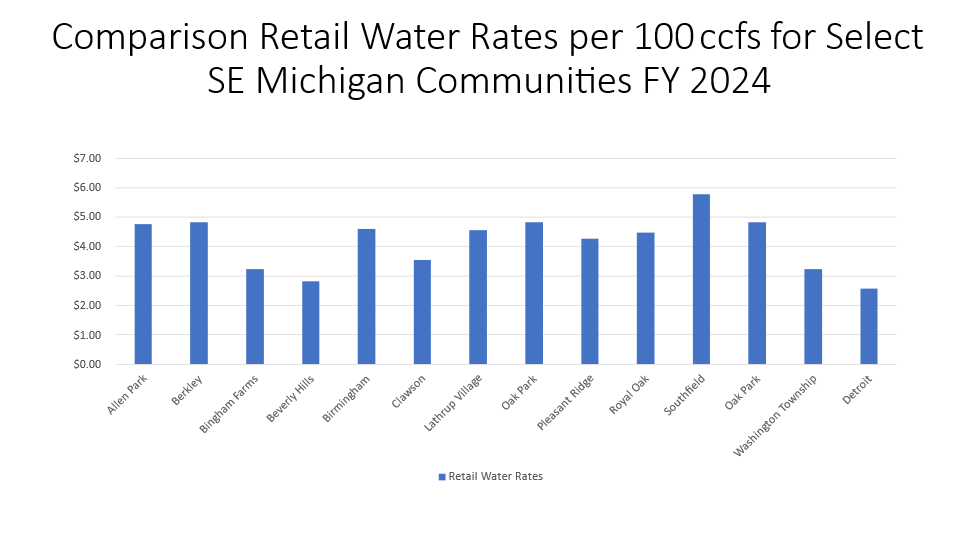

The GLWA adopted wholesale rates for communities can be found here. While a comprehensive of list of retail rates does not exist, the above chart shows a comparison of retail water rates amongst several communities in South Oakland County (data provided by the South Oakland County Water Association), along with the rates for Allen Park, Washington Township and Detroit. The chart shows that Detroit, which sets its own rate, has the lowest water rate of the communities. Detroit purchases its water from the Detroit Water and Sewer Department, and not GLWA. The City of Southfield has the highest retail water rate at $5.79 per ccf. Washington Township, which is 36 miles from Detroit, has a retail water rate of $3.24 per ccfs.

The elements of water rates are important to understand as the public debates the potential creation of a statewide affordability fund for low-income residents to access. It should also be noted that part of the revenue the GLWA earns from its customers goes into the Water Residential Assistance Program (WRAP). With this program,0.5 percent of the GLWA’s revenues go into an Income Based Plan that provides bill credits to eligible households. This plan makes it so that the water bill does not exceed 3 percent of household income for up to two years (or ongoing for households with senior citizens and persons with permanent disabilities).

This post demonstrates not only how complicated our water system is, but also the way in which rates are determined. The true cost of delivering clean water is only a piece of the equation, and that varies from one community to the next. Even with such fluctuation in what ratepayers/taxpayers pay for their water, one thing is certain, rates are only increasing. Water infrastructure is aging, the cost of electricity (used to help deliver water) is increasing, staffing costs are increasing and clean water remains a necessity for life. With such factors coming into play in determining already complicated retail water rates, a reliable source of assistance for those in need can, and should be, a constant. For this reason we support the proposed State of Michigan plan to add a $2 flat fee on all our monthly bills to help the poor pay for their water. No one should have to go without water.

[1] A centrum cubic feet equals 100 cubic feet or approximately 748 gallons of water.