In Michigan, cities, townships, villages, and other municipalities cannot levy their own sales taxes. Only the state government collects and levies sales taxes. In fact Detroit asked permission to levy a 1% sales tax as it descended into bankruptcy—the State Legislature said, “no.” The rationale for this centralized system of sales tax is that having lots of different sales tax rates is confusing to consumers, imposes a burden on businesses, and can lead to unhealthy competition among municipalities. There are other states that permit municipalities to create their own sales taxes (e.g., Missouri), and this leads to situations in which the same product is taxed at a different level depending on whether it is purchased in City “A” or an adjoining Township “B” a few blocks away.

The argument that has prevailed in Michigan is that it makes sense for the State to establish one sales tax rate, collect the tax revenue, and then “share” it with municipalities and other units of government in the state. But this system relies on the premise that the State of Michigan will be an honest broker and share the revenue equitably, responsibly, and reliably. This assumption has been challenged in recent years.

There are two categories of revenue sharing in Michigan—constitutionally mandated and statutory revenue sharing. The latter is based on laws that the legislature can alter; the former is more securely enshrined in the state constitution. But even constitutional revenue sharing can decrease when overall revenue declines, as it tends to during recessions, or when the population of a municipality declines. As we see below, in recent years the State of Michigan has stopped sharing as much revenue as it had historically. Some observers argue that in recent years the State of Michigan balanced its budget on the backs of municipalities throughout the state by taking the lion’s share of the revenue raised from the sales taxes. Additionally, components of the revenue sharing formula change as different political parties seek to provide more revenue to districts represented by legislators from that political party as they try to protect the interests of their constituents.

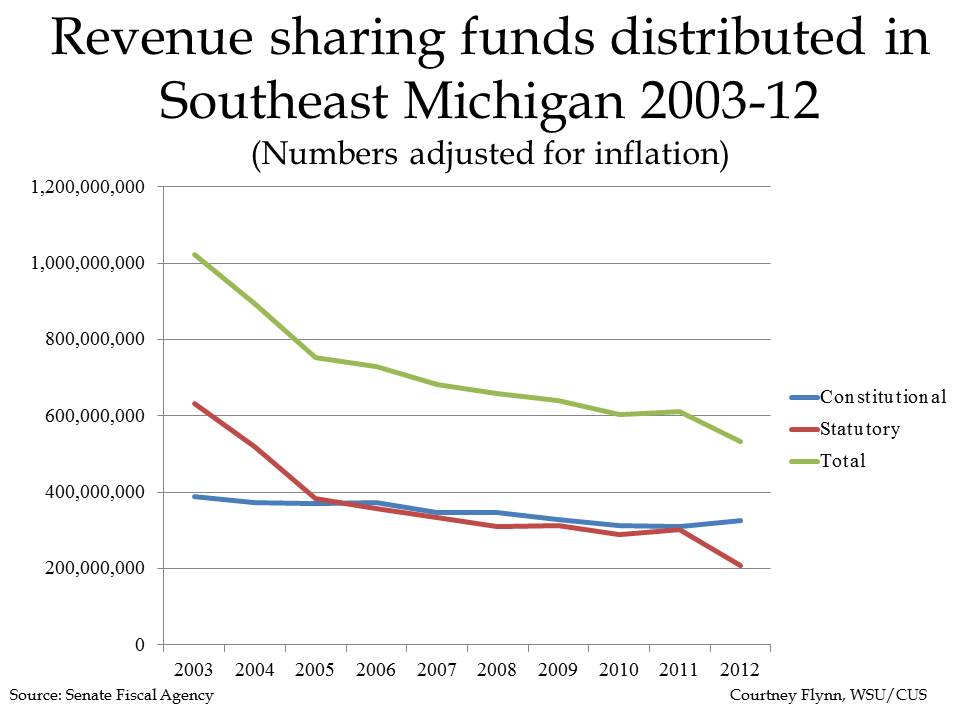

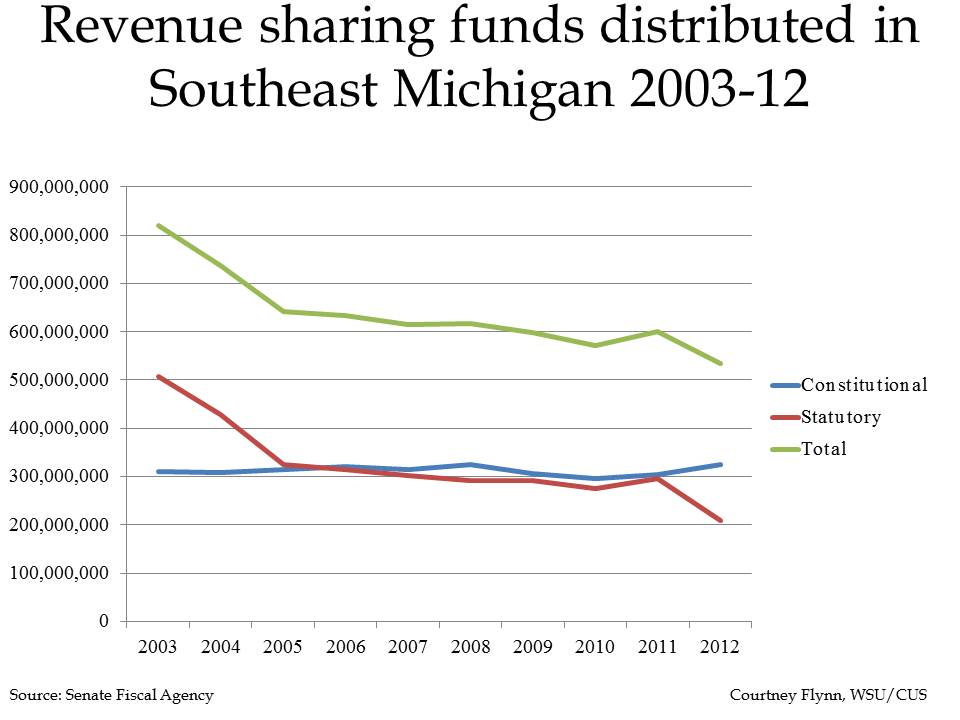

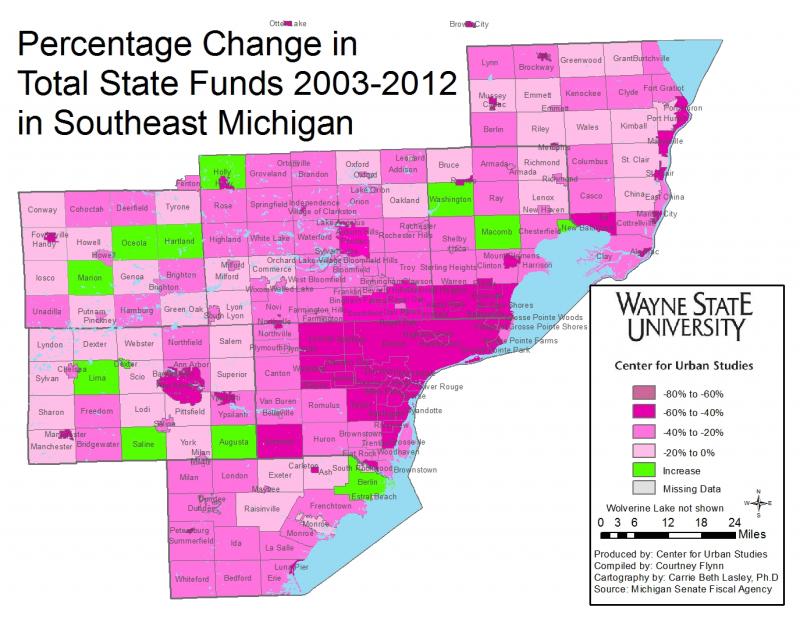

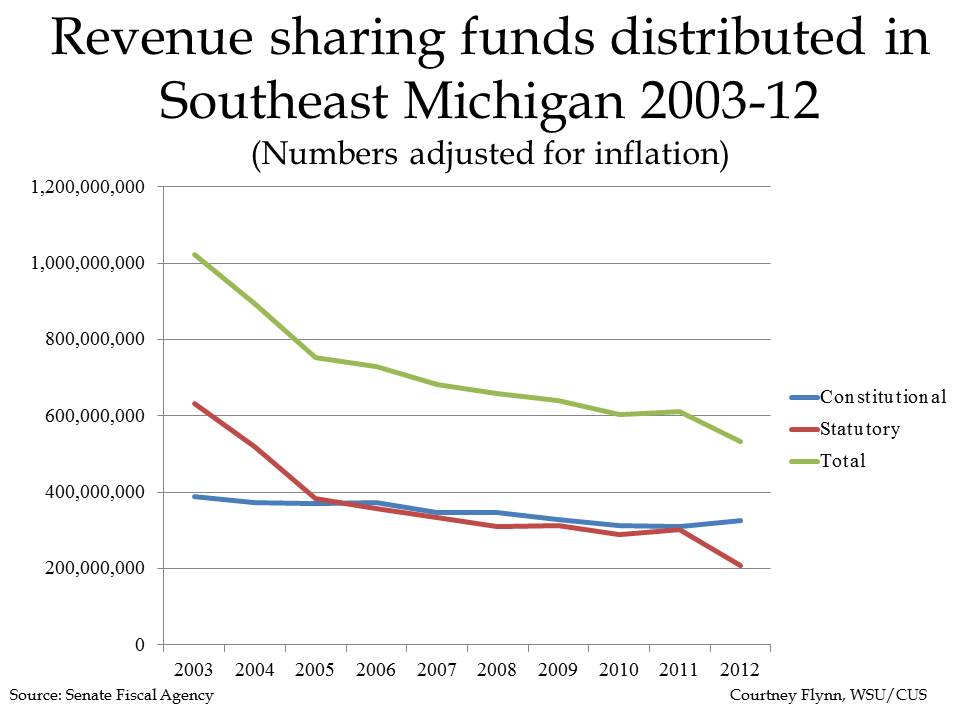

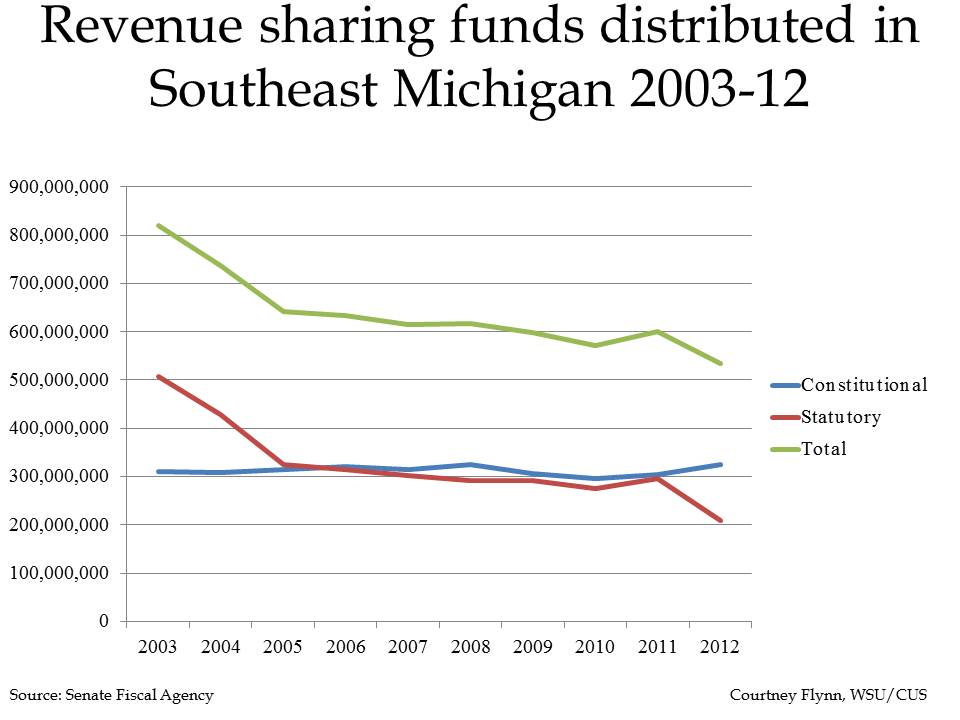

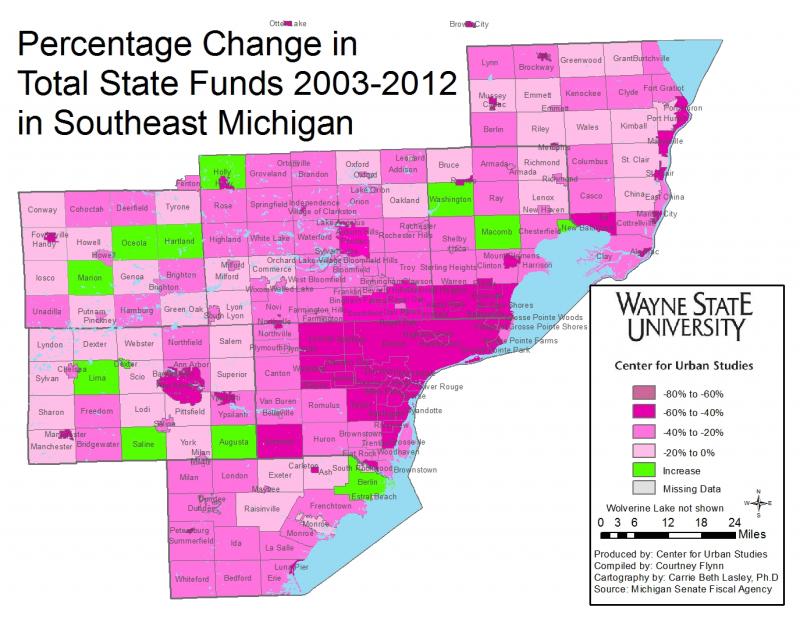

In the past decade the Southeastern Michigan has been on the losing end of the “revenue sharing” arrangements. Since 2003 the region has experienced a 47.8 percent decrease in combined revenue sharing- constitutional and non-constitutional-, according to the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency.

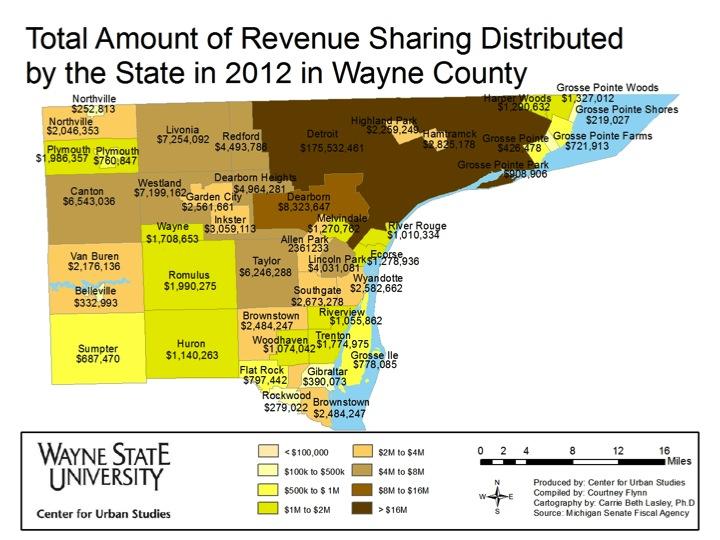

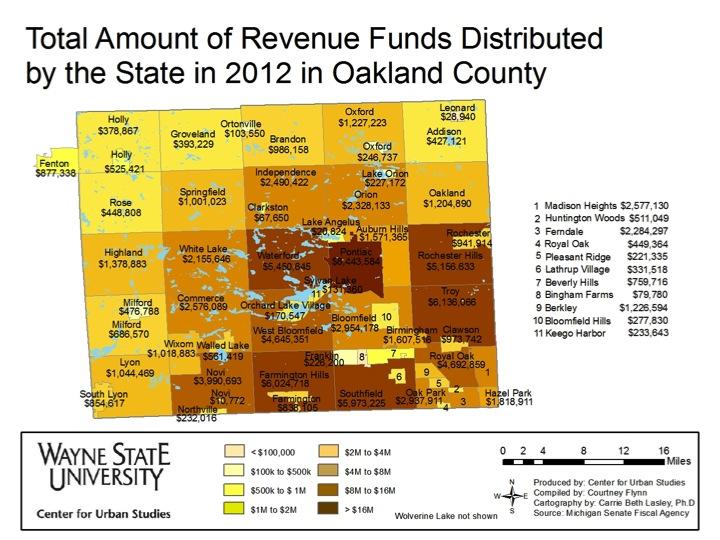

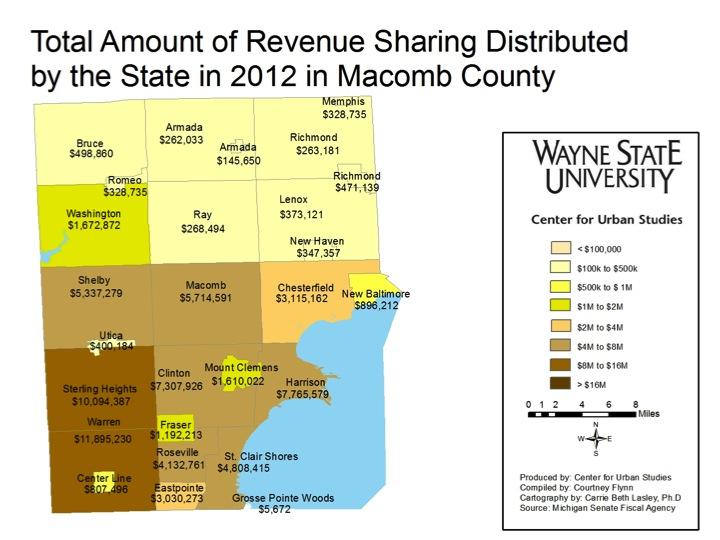

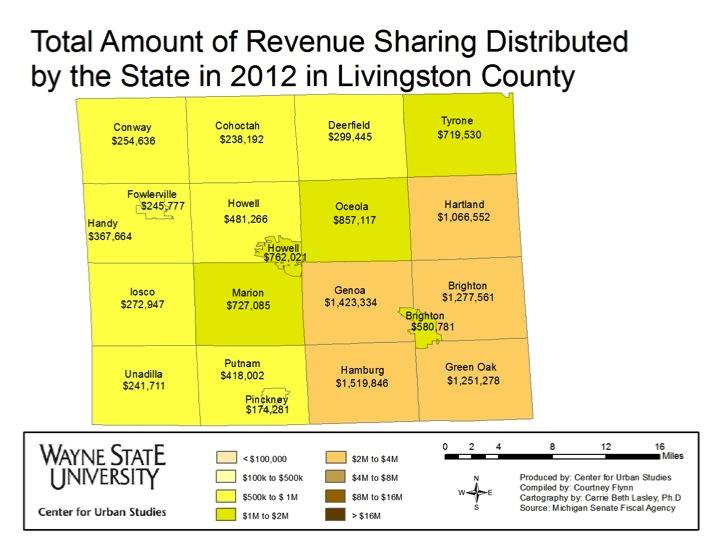

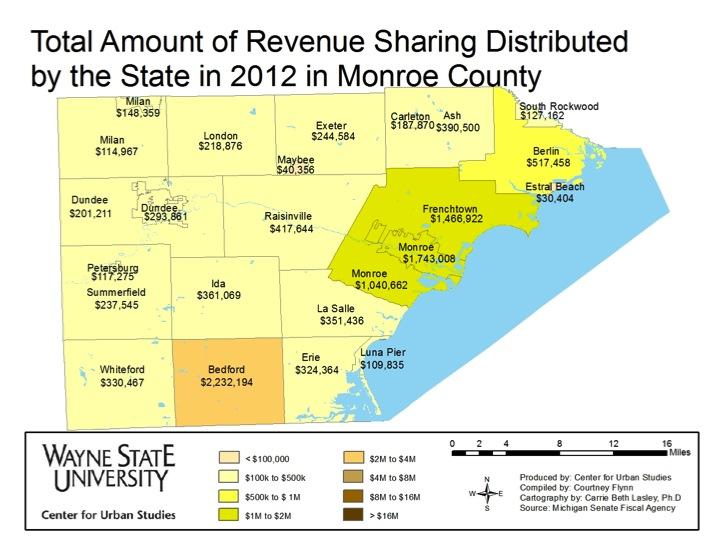

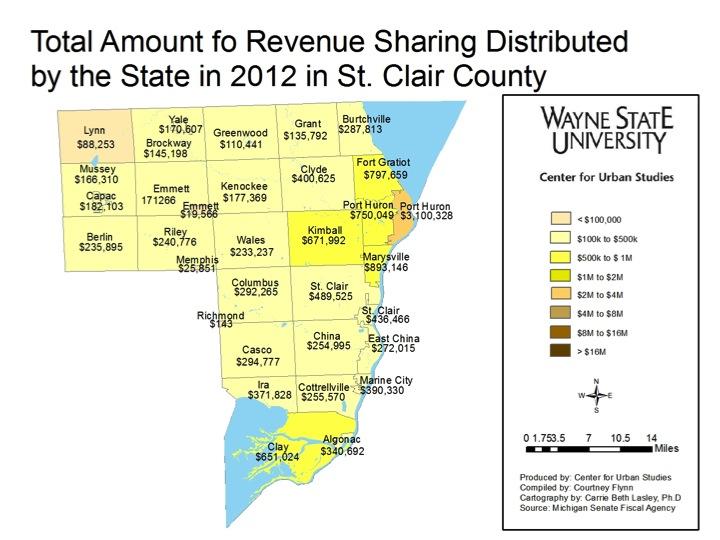

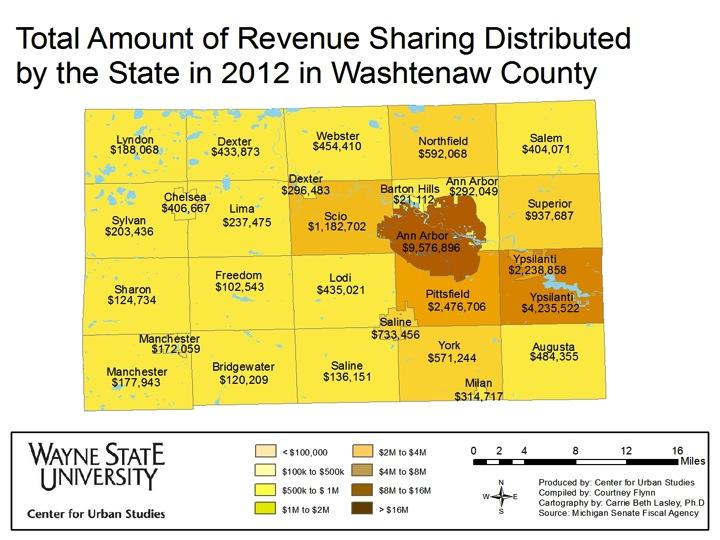

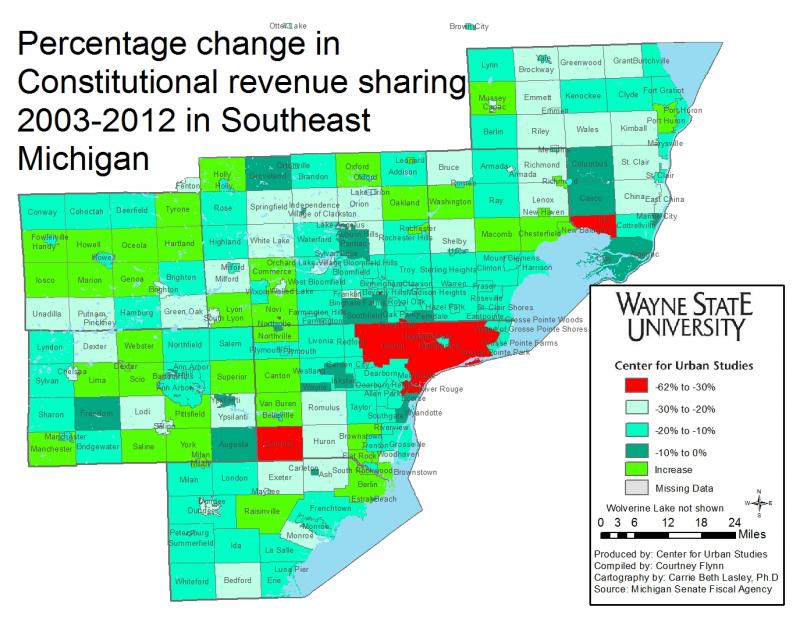

There are 231 municipalities that make up the seven-county Southeast Michigan region (Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, St. Clair, Monroe, Livingston and Washtenaw), and of those only 13 did not experience a loss in revenue sharing. These communities are: Macomb Township, Washington Township, New Baltimore, Berlin Township, Holy Township, Augusta Township, Lima Township, Saline Township, the Village of Dexter, Conway Township, Hartland Township, Oceola Township, and Marion Township. In contrast, 147 of the 231 municipalities in the region experienced a decrease in revenue sharing of 25 percent or more between fiscal years 2003 and 2012. Highland Park experienced the largest decrease in revenue sharing, at 57.17 percent. The City of Detroit was close behind, losing 56.76 percent of its total revenue sharing funding from the state between 2003 and 2012.

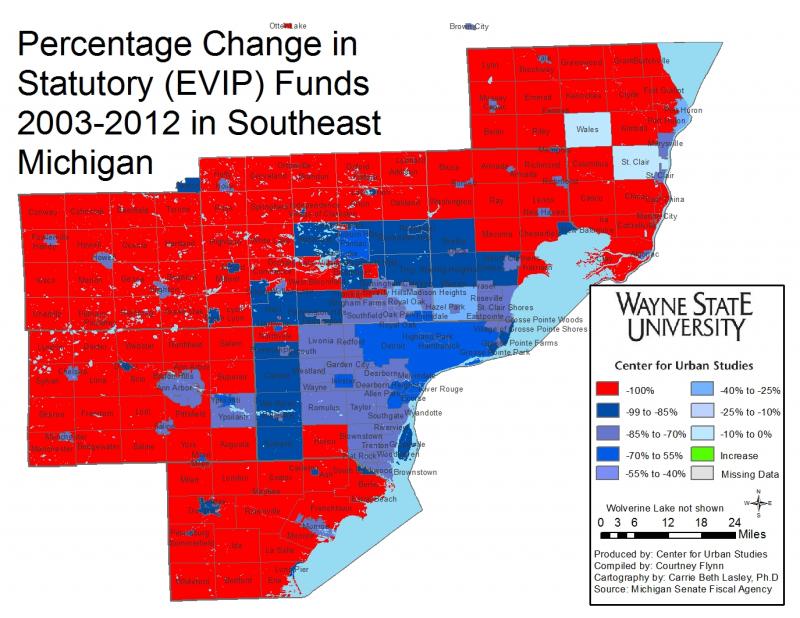

Since the 1930s municipalities in the State of Michigan have received revenue sharing payments from the state government (See attached “A Little Bit of History” at the end of this post.). The distribution of these funds has changed, however, over the years, most recently during the 2011-12 fiscal year and especially for non-constitutional funding, formerly called “statutory revenue sharing.” In 2007, a formula was created that included an annual budget bill boilerplate, according to Michigan in Brief. “Statutory revenue sharing” was renamed the Economic Vitality Incentive Program (EVIP) in the 2011-12 fiscal year. In order to earn EVIP funds, municipalities must meet requirements set forth by the state related to transparency, coordination of services, and employment compensation, according to the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency.

While the EVIP funding now depends on a community’s willingness, and ability, to comply with those requirements, there are no such stipulations for the constitutional funding provided to such communities. Michigan’s sales tax rate is 6% and of, that two percent goes to the school aid fund. Fifteen percent of the remaining 4 percent in sales tax revenue is “shared” with the municipalities on a per capita basis. The U.S. Census population figure used by the state is adjusted so that 50% of the institutional population (e.g., prisoners) is removed from the population count, according to the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency. After the release of Census data, each municipality’s constitutional revenue sharing percentage is adjusted based on its new population figure. For example, following the release of 2010 Census data, Macomb Township, which had an increase in population, also experienced an increase in revenue sharing funding. The City of Detroit which experienced population loss, then also had a decrease in revenue sharing.

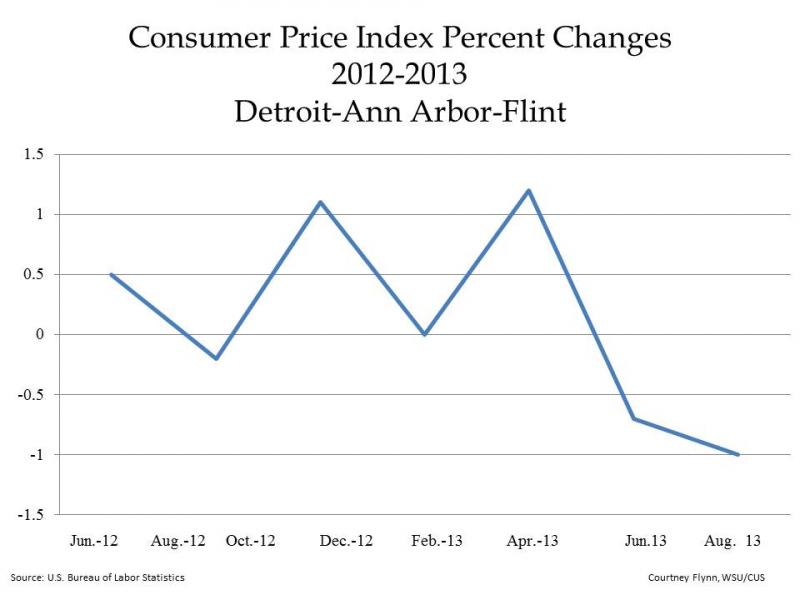

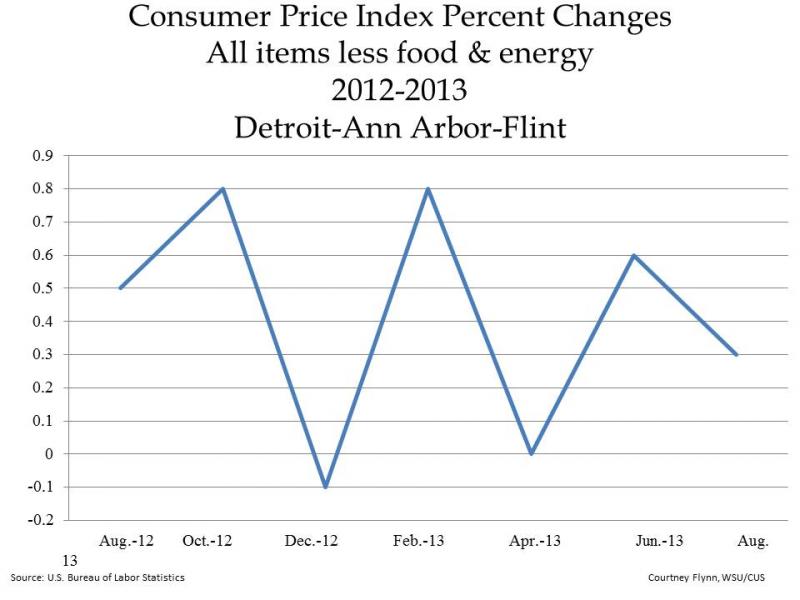

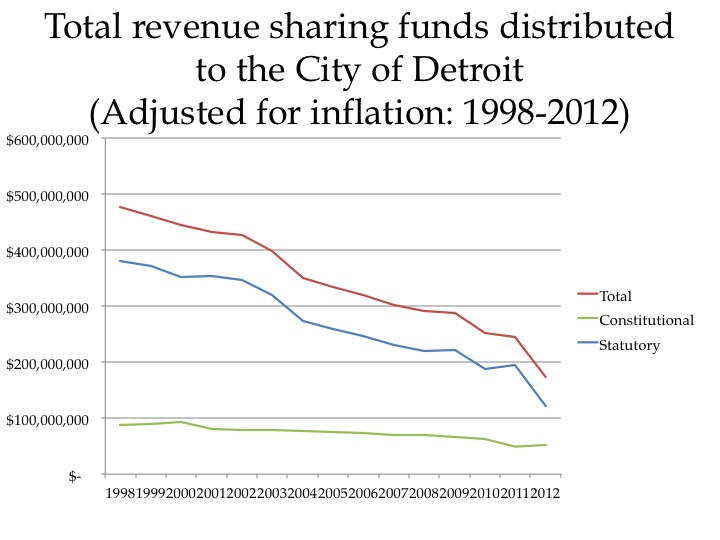

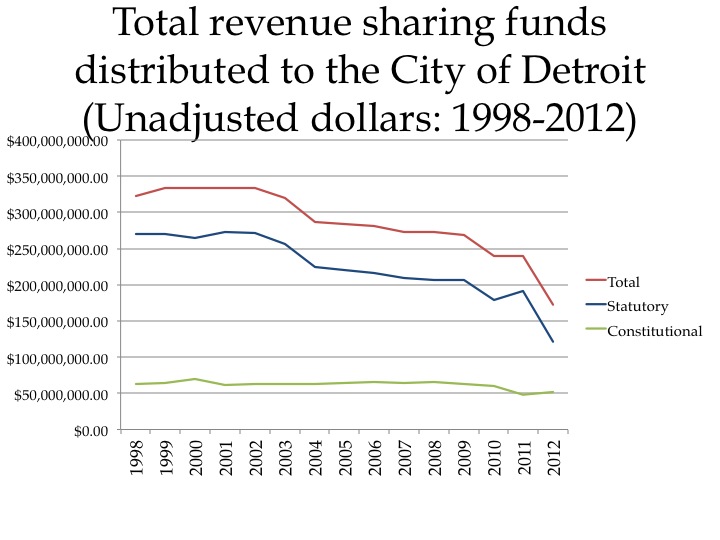

The percent change numbers shown in these posts present both the 2003 and 2012 data adjusted to the 2012 Consumer Price Index (CPI).

The “actual” revenue sharing numbers for 2003-2011 are adjusted for inflation using the 2012 chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) published by the U.S. Department of Labor–the most recent year for which an annual CPI is available. Each year’s revenue sharing allotment is therefore raised to 2012 dollars using standard CPI adjustment formulas such as those used by the Health Economics Resource Center. This approach, verified using the Department of Labor’s inflation calculator, treats all values as 2012 dollars and reveals a more complete picture of revenue sharing changes over time.

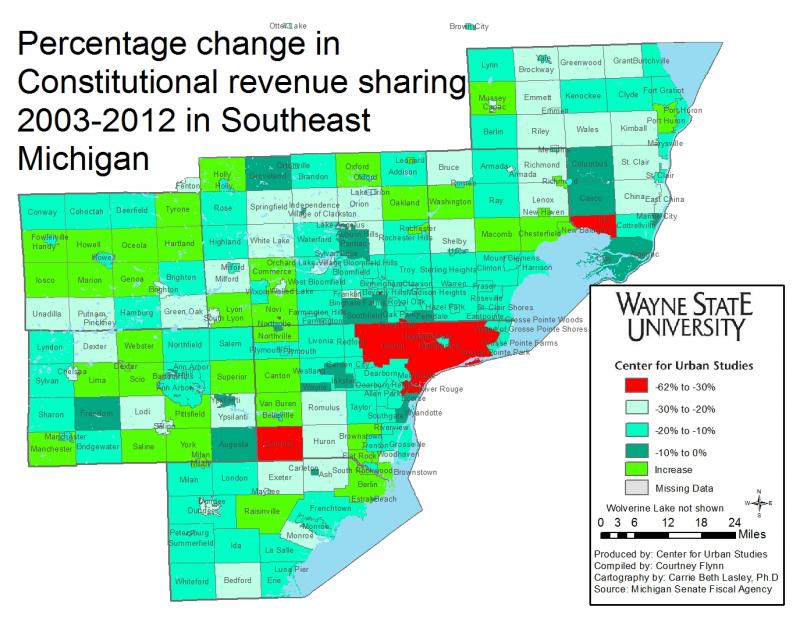

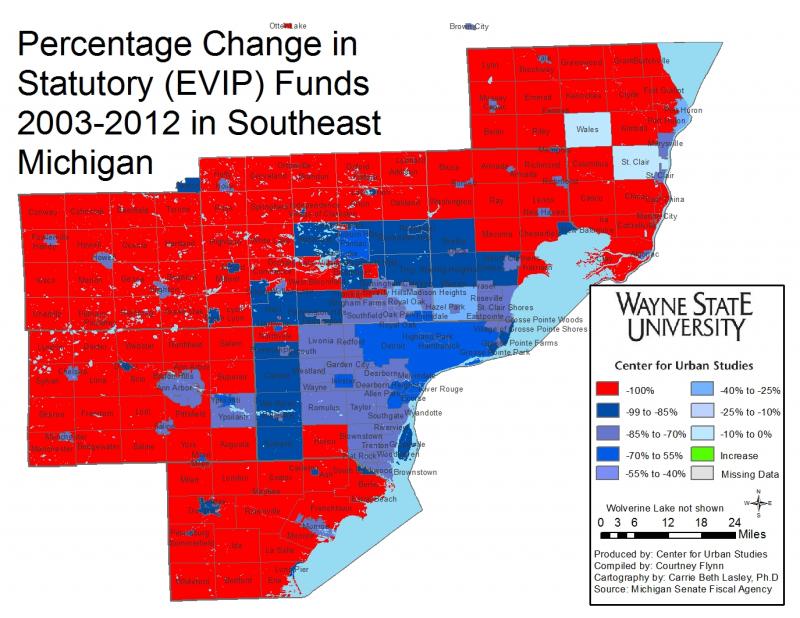

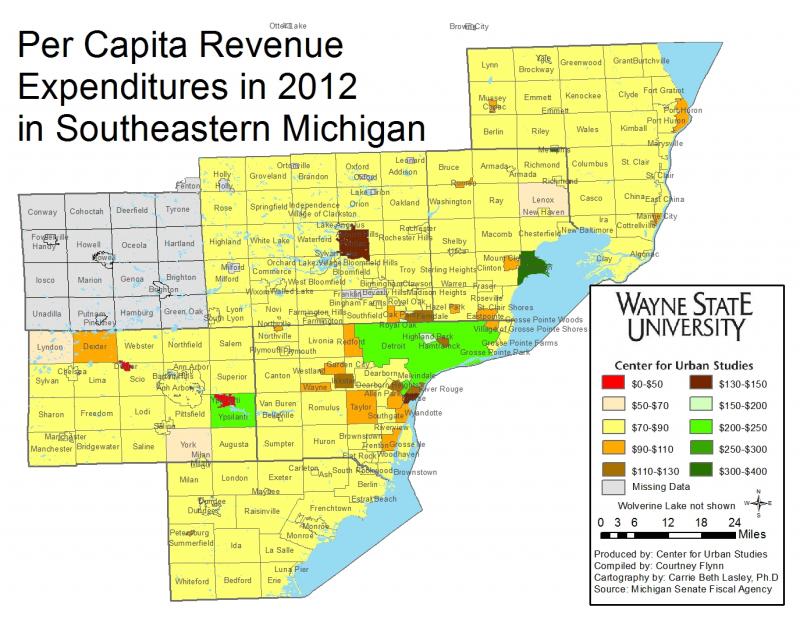

Over the next two weeks, Drawing Detroit is displaying maps showing the following:

- the percent change in total revenue sharing for each municipality in Southeast Michigan between 2003-2012;

- the percent change in statutory funding;

- the percent change in total funding;

- the per capita revenue expenditures for each municipality; and

the amount of total revenue sharing funds provided to each community in 2012.

The above two charts show the total amount of revenue sharing funds distributed to the Southeast Michigan region from 2003 to 2012. The first chart shows the inflation adjusted amount of funds distributed each year and the second chart shows the amount of real dollars distributed. Both charts show that while constitutional revenue sharing has remained fairly steady since 2003 there has been a decrease in the amount of statutory, or non-constitutional, revenue sharing funds distributed.

The above map demonstrates the percent change in constitutional revenue sharing funds from 2003-12 (CPI adjusted). Detroit lost 35.2 percent of its constitutional funding in that time; Royal Oak Township lost 61.5 and Ira Township lost 36 percent. While the map shows that majority of the municipalities that make up Southeast Michigan experienced a decrease in constitutional revenue sharing funds; there were 38 municipalities with a percent increase in constitutional funding. Dexter Township experienced the highest percent increase at 50.2 percent; New Baltimore came in next at 41 percent.

None of the municipalities that make up Southeast Michigan experienced a percent increase in statutory, now known as Economic Vitality Incentive Program, funding from 2003-2012. As noted earlier, there were changes in the way statutory funds were earmarked and distributed in 2007 and 2011. There were 121 municipalities that did not receive in EVIP funding in 2012. A community is not provided their portion of EVIP funding if they do meet requirements related to transparency, coordination of services, and employment compensation set forth by the state.

Highland Park lost 57.17 percent of its total revenue sharing (CPI adjusted) from 2003 to 2012 and the City of Detroit is a close second losing 56.8. In total, the entire region experienced a loss of 47.7 percent of revenue sharing. According to information provided by the Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency, only 11 municipalities experienced a percent increase during that time period.

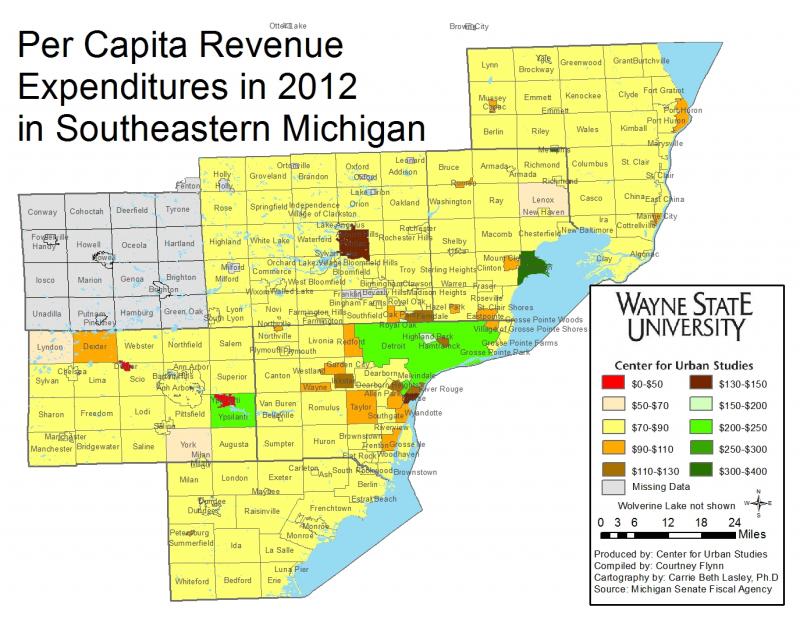

The above map shows per capita revenue expenditures for Southeastern Michigan in 2012. Detroit’s per capita revenue spending was $245.9, which was the second highest in the region. Harrison Township had the highest per capita revenue expenditures in the region at $315.8. The Village of Dexter had the lowest at $49.1 per capita. Data for Livingston County were not available because of the federal government shutdown.

In next week’s post, we will take a more in-depth look at the loss of revenue sharing in Detroit from 1998 to 2012. Also, a map for each county will show the actual amount of total revenue sharing each municipality received in 2012.

A Little Bit of History:

In 1933 the State of Michigan began collecting funds by taxing establishments that served liquor. Of those funds collected, 85 percent of it was returned the municipalities in the state, according to the Michigan Municipal League (MML). Six years later, in 1939, the state shared portions of the new state intangibles tax—formerly a source of local funding—with cities, villages, and townships; the portion that was removed was the intangible property tax. Then, in 1946, portions of Michigan’s sales tax were earmarked for local government funding. Such funding operations continued until 1963, when a change in the state constitution guaranteed one-eighth of the funds garnered from sales taxes would be devoted to local governments, according to the MML.

In 1972, Public Act 212 tied the relative tax efforts (RTEs) of cities, villages, and townships to the portion of state income tax revenues they received, according to Michigan in Brief. The RTE compares a municipality’s property, income, and excise taxes to that average of all municipalities within the state. This change in statutory funding was to put more focus on a municipality’s needs-beyond population-because different municipalities may need different public services but have different revenue-raising abilities beyond those based on population, according to Michigan in Brief. Then, in 1974 the amount of tax revenue earmarked for constitutional revenue sharing increased from one-eighth to one-fifth of the funds brought in each year. This was after citizens in the state voted to have food and drugs exempted from the sales tax. A year later, other changes occurred, again focused toward statutory revenue sharing because whatever the full amount of constitutional revenue sharing calculated by the Michigan Legislature each year must be distributed. Not only was the Small Business Tax enacted, where portions of it were received each year by local governments and included in RTE, but also counties were only given 35 percent of income tax distribution, as opposed to 50 percent previously given to them, and municipalities were given 65 percent.

Aside from some statutory revenue sharing payment reductions in the 1980s and 1990s because of state budget problems, the distribution of revenue sharing funds remained steady. Then, Public Act 342 of 1996 was enacted and the following changes occurred for statutory revenue sharing:

- The amount of funding each community received under the RTE funding was capped at the 1996-97 fiscal year level. If there was a growth in a revenue source it was to be distributed on a per capita basis;

- A bi-partisan task force was created and was charged with recommending various sources and distribution methods for revenue sharing in the future. If the task force stalled before funds were to be distributed, municipalities would receive the same funding from the year before and, if they were to receive additional monies, it would be put into a reserve fund until actions were taken.

- Sales and small business taxes were removed as sources of revenue sharing funds; additional sales tax revenue replaced this.

(According to Michigan in Brief)

Then, in 1998, Public Act 532 was enacted so a new formula could be phased in over a 10 year period. Part of this formula called for 23.1 percent of sales tax revenue to be distributed to municipalities. However, because of budget deficits and funding shortfalls, the 1998 formula has yet to be fully implemented for statutory funding, according the MML. According to the Michigan Department of Treasury though, 21.3% of the 4% gross collections of the state sales is currently distributed to Michigan municipalities for statutory funding.