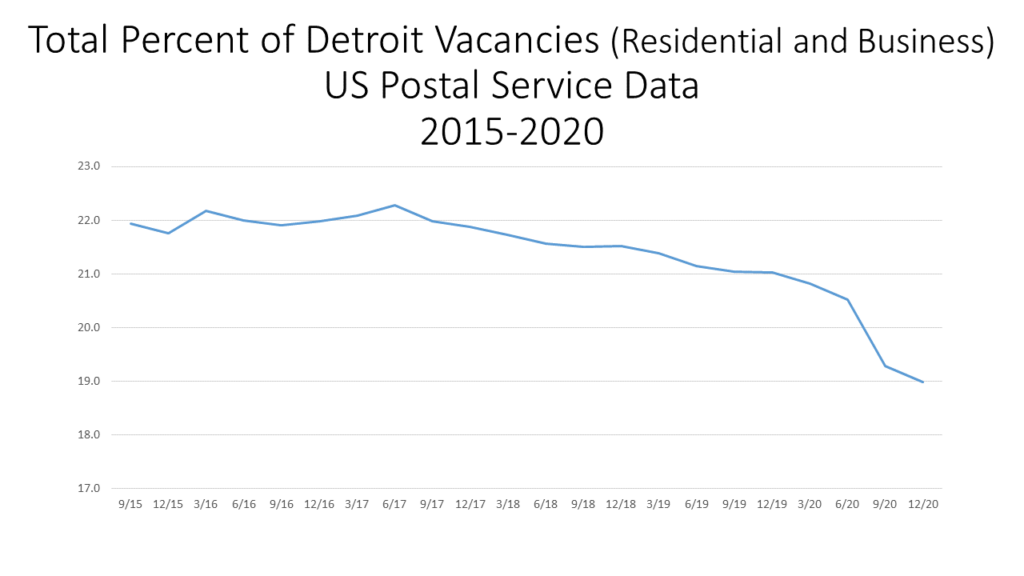

In December of 2020 the US Postal Service reported 74,313 total vacant properties in the City of Detroit, equivalent to a 19 percent vacancy rate. This rate is the lowest report rated since 2015, as can be seen in the first chart below. Additionally in 2020 the Postal Service reported 317,272 occupied addresses.

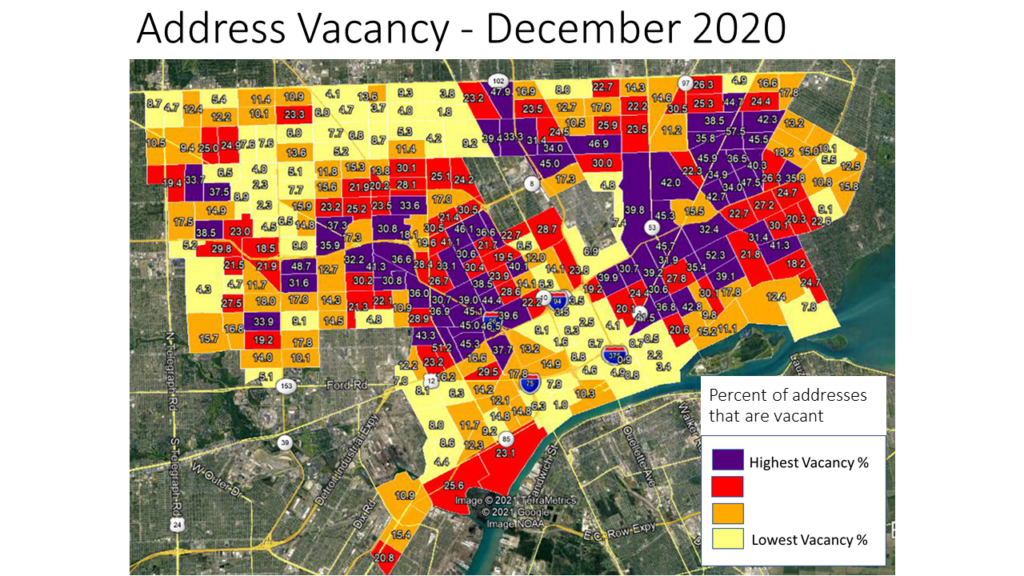

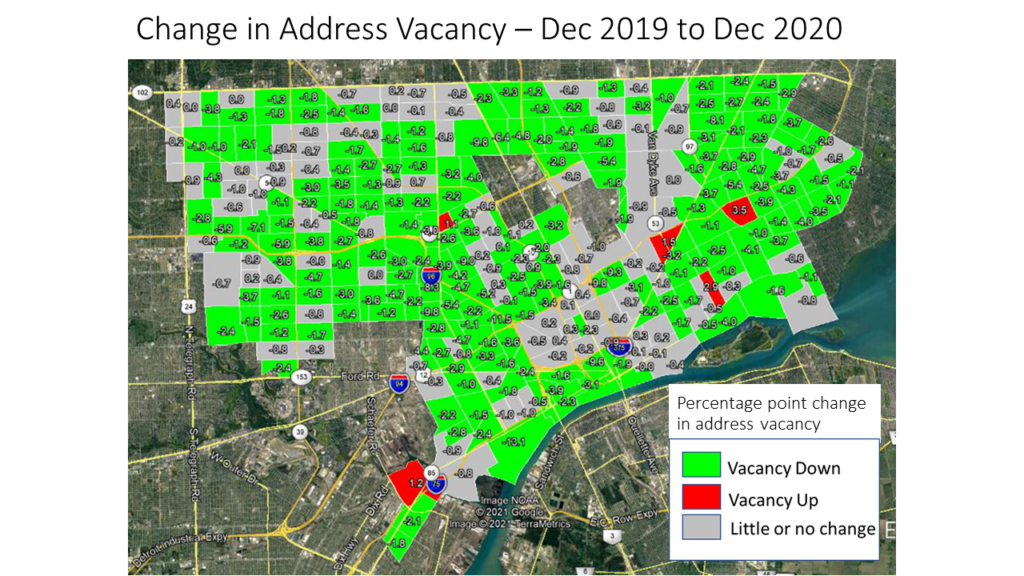

According to the first map below, while the overall vacancy rate in December of 2020 was 19 percent, there were several areas in the City with much higher rates. The highest rates were near I-96 and Gratiot Avenue in the City of Detroit, with the highest overall rate for a Census Tract being 52.3 percent in the Morningside/Chandler Park area. Conversely, vacancies remained the lowest in the Downtown Detroit area and Green Acres/Pembroke/Bagley areas. High vacancy rates in the City ranged from 31-52.3 percent and low vacancy rates ranged from 1.9 to 9.3 percent. Between September and December of 2020 the vacancy rate decreased by 0.3 percent. Additionally, the vacancy rate had an annual 2 percent decrease plus a 2.8 percent decrease over a five-year time period. The second map below shows the long-term trends; all but seven Census Tracts experienced a decrease in vacancy or little to no change between 2019 and 2020. The Chandler Park area had the highest increase in vacancy rates between December 2019 and 2020 at 3.5 percent.

The USPS provides aggregate vacancy and no-stat counts (see explanation below) of residential and business addresses that are collected by postal workers and submitted to on a quarterly basis the Department of Housing and Urban Development. While occupancy status is recorded, USPS does not capture any information about the nature of the vacancy or the address itself, other than whether it is a residential or business address. To the USPS, the address is either occupied and requires mail service or is vacant and does not. An address is deemed vacant if it did not collect mail for 90 days or longer. In addition to occupied and vacant addresses there are also “no stat” addresses. A “no stat” address is called that if it is under construction and not yet occupied or is in an urban area and identified by a carrier as not likely to be active for some time.

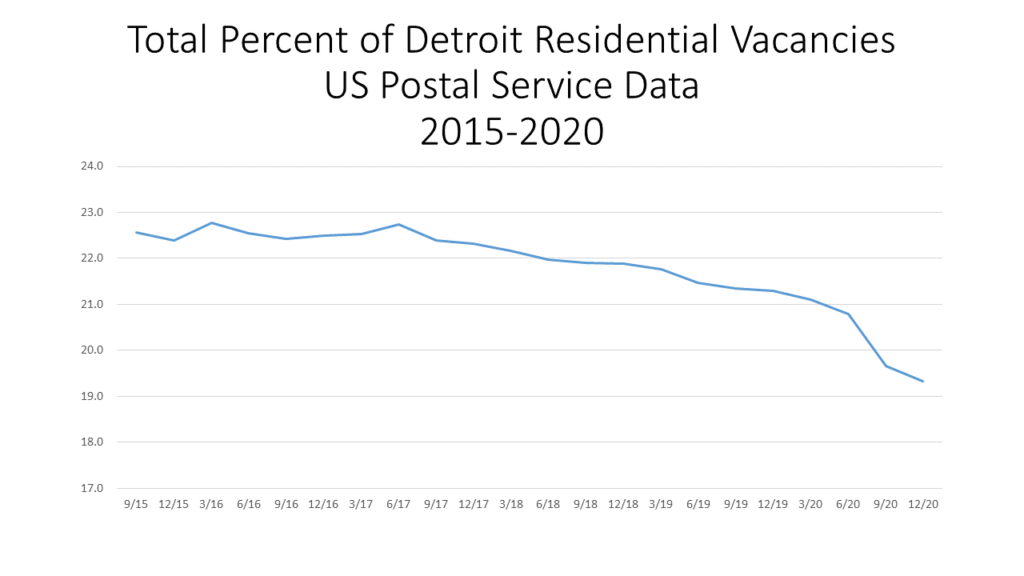

As noted, overall vacancy rates in the City of Detroit have been declining, and this also true at both the residential and business levels. Residential vacancy rates in September of 2015 were 22.6 percent, which was equivalent to 81,666 residential vacancies. By December of 2020 that number of vacancies decreased to 19.3 percent, or 67,442 total vacancies.

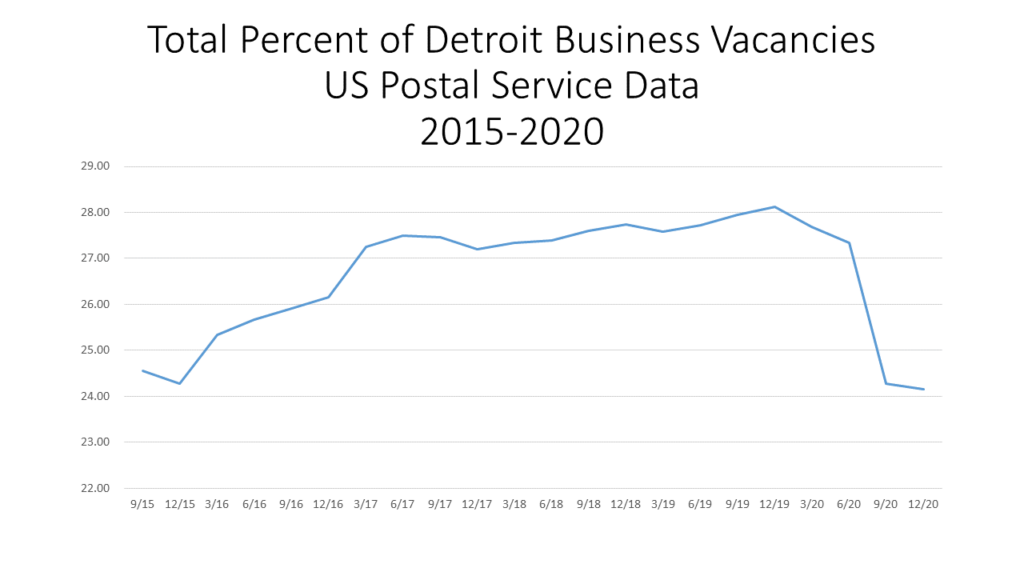

For business vacancies in December 2020 there was a total of 6,871 vacant businesses out of 28,438 total businesses in the City. This was equivalent to 24.2 percent. In September of 2015 the vacancy rate was 24.6 percent for a total of 7,337 vacant businesses out of 29,885.

Examining both charts below we see that there has been a steadier decline in residential vacancy rates than business vacancy rates. Between 2015 and 2019 business vacancies were actually climbing, and reached a high of 28 percent in December of 2018. Then, through the pandemic declined substantially, though it is not clear why.

According to the USPS there was 27,878 “no stat” addresses reported in Detroit in December of 2020, an increase of 3,884 from the year prior.