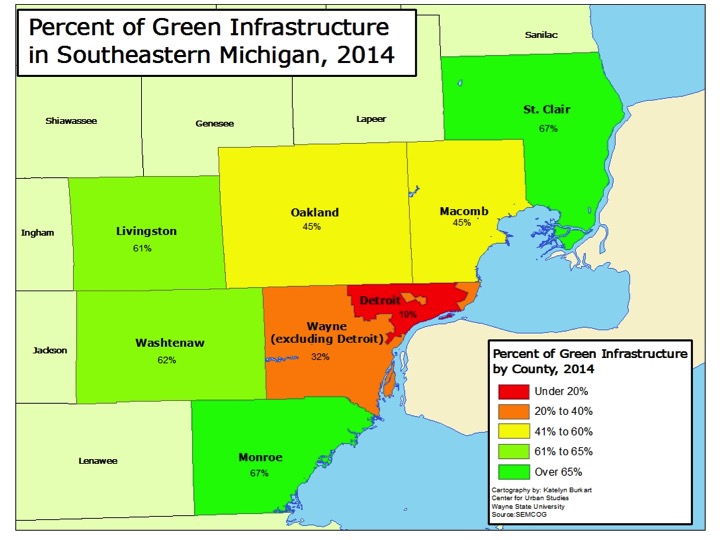

In Southeastern Michigan there was about 180,000 acres of green infrastructure in 2014, according to the Southeastern Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG), and the regional planning agency is looking to improve and grow that number. This green infrastructure represents both natural ecosystems (wetlands, forests and parks), agricultural land and constructed versions, such as community gardens and bioswales. Both Monroe and St. Clair counties had the highest percentage of total green infrastructure in 2014 at 67 percent. Wayne County, both including and excluding Detroit, had the lowest percentage of green infrastructure. Excluding Detroit, Wayne County was made up of 32 percent of green infrastructure; including Detroit Wayne County was made up of 30 percent green infrastructure. In general, one can think of green infrastructure as the inverse of developed land, where houses, businesses, roads and other infrastructure exists.

Of this overall green infrastructure it is important to identify what it is comprised of. Below we will see how the tree canopy varies from county to county and how these variations are affected by the presence of parks and agricultural land.

The data provided for this post was found in SEMCOG’s 2014 Green Infrastructure Vision document.

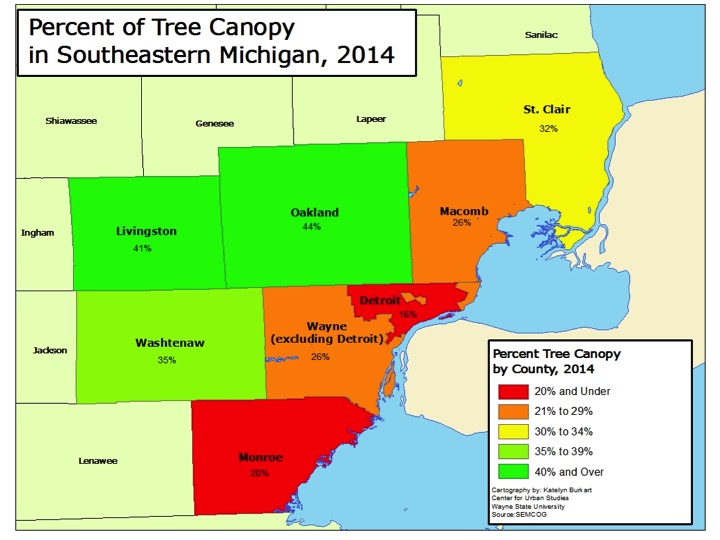

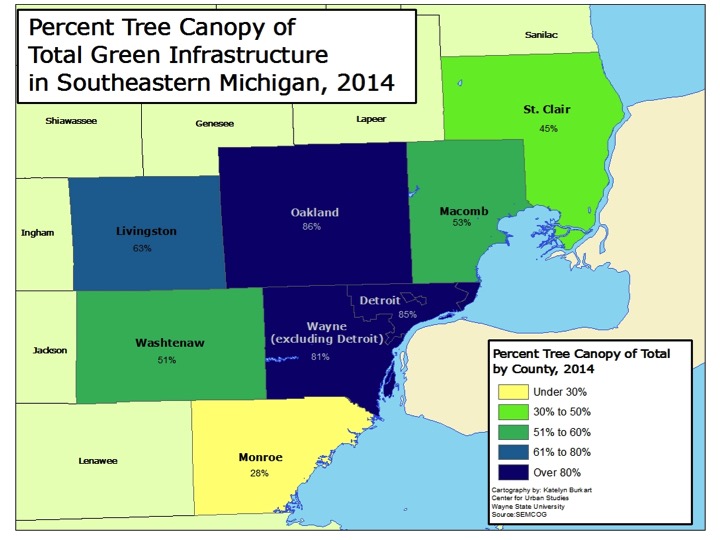

In total, Oakland County had the highest percentage of overall tree canopy at 44 percent; the county’s tree canopy made up 86 percent of its total green infrastructure. Oakland and Livingston counties were the only two in the region that had a tree canopy above the American Forest’s overall standard of 40 percent. The American Forest is the country’s oldest conservation non-profit, and SEMCOG bases its green infrastructure goals on their standards.

The county with the lowest overall tree canopy was Monroe; it had a tree canopy of 20 percent. This 20 percent of total tree canopy made up 28 percent of its total green infrastructure. This is largely because of the greater portion of land devoted to agriculture, as discussed below.

The city of Detroit had a total tree canopy of 16 percent, which is below American Forest’s standard for tree coverage in an urban area. Nevertheless this represents 85 percent of Detroit’s green infrastructure. American Forest calls for a 25 percent tree canopy coverage in an urban area. In a suburban residential the organization’s standard is 50 percent, and in a central business district that standard is 15 percent.

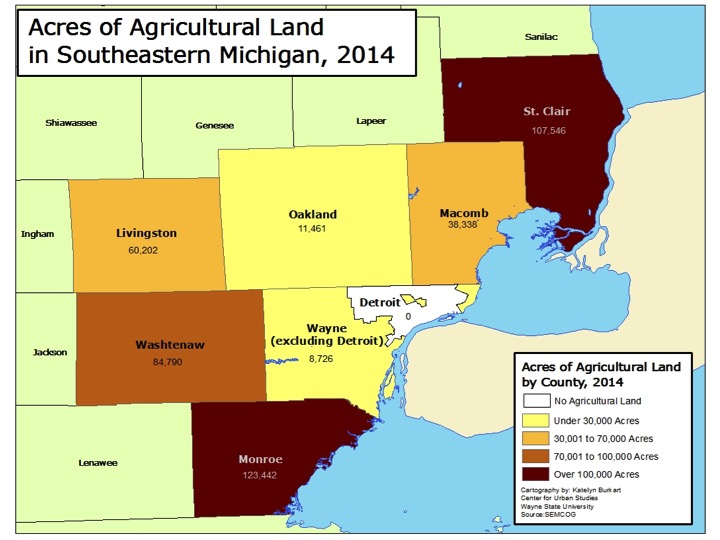

While tree coverage is an important aspect of green infrastructure, it is not the only thing that can make a community “more green.” As discussed above, Monroe County had the highest percentage of overall green infrastructure yet the lowest percentage of tree canopy coverage. As shown below, this is, in part, because there was more than 123,000 acres of agricultural land in Monroe County in 2014. Monroe County had the highest amount of agricultural land in 2014 in the region followed by St. Clair County, which had about 107,000 acres of agricultural land. St. Clair County, like Monroe County, was made up of 67 percent green infrastructure. According to SEMCOG, Monroe County ranks seventh in the state in the total number of acres of vegetables (6,707) and corn, soy and wheat (169,792). St. Clair County ranked sixth in the state in the number of farms producing organic products and eighth in state for the total number of acres of soybeans it produced in 2014 (64,224).

According to SEMCOG, agricultural land is defined as “rural land used with the growing of food as the primary function, but can also provide ecological benefits.” SEMCOG classified Detroit as having 0 acres of agriculture, but this does not include the number of community gardens, which have been growing in the city through individual and organizational efforts.

While Detroit had 0 acres of agriculture land, Wayne County had 8,726 acres of agricultural land, which was the smallest amount in the region.

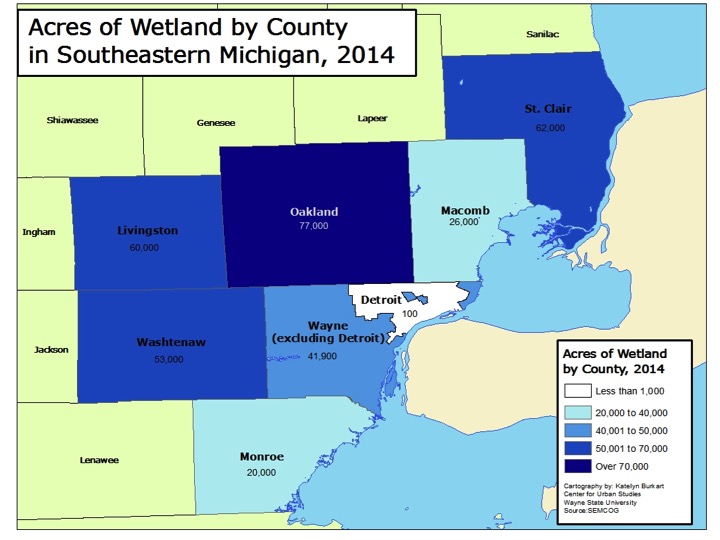

For total acreage of agricultural land in the region, Oakland County had amongst the smallest amount of coverage in the region but for wetland coverage it had the greatest amount. Oakland County had 77,000 acres of wetland in 2014. St. Clair (62,000 acres), Livingston (60,000) and Washtenaw (53,000) counties all had more wetland coverage than Wayne County. However, the 41,900 acres of wetland coverage in Wayne County was nearly five times the amount of agricultural land in the county. Additionally, of those 41,900 acres, 100 were located in Detroit.

Monroe County had the least amount of wetland coverage at 20,000, which is about 100,000 less acreage than it had of agricultural land.

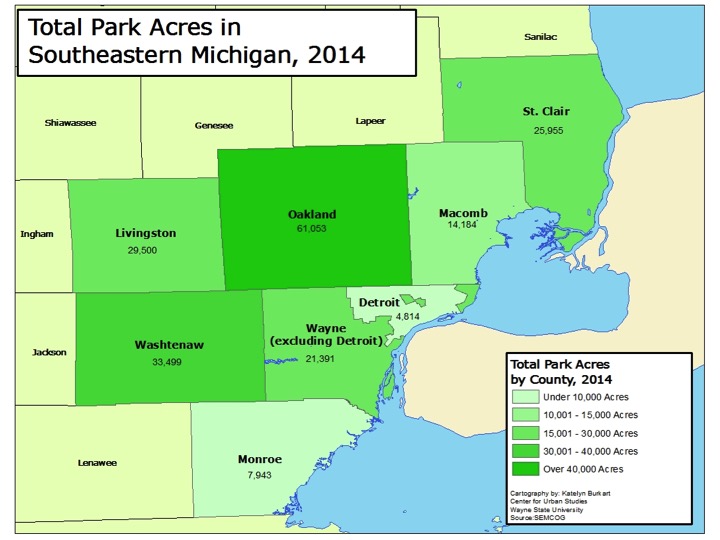

Another factor into the total amount of green infrastructure present in a county is park land, which includes city, country, metro and state parks. Oakland County had the highest amount of park acreage at 61,053. Oakland County is home to five state park/recreation areas, three metroparks, 13 county parks and numerous local parks at the municipal level. Washtenaw County had the second highest acreage of park coverage at 33,499 acres, which was nearly half of Oakland County’s coverage. Like Oakland County, Washtenaw County is home to three metroparks and 13 county parks. Washtenaw County also has 20 nature preserves, numerous parks at the local level and nine state park/recreation areas.

Wayne County had about 26,000 acres of total park acreage, about 5,000 of which was located in Detroit. Belle Isle made up nearly a fifth of Detroit’s park acreage; it is 982 acres.

The amount of green infrastructure established in a community and a region is important because it can not only serve as a catalyst for economic growth but also because it serves as the base for ensuring citizens have access to clean water and air, fresh food and amenities that promote healthy and sustainable lifestyles. There is a recognition that additional green infrastructure is needed in Southeastern Michigan, which is why SEMCOG has created a green infrastructure vision. This vision aims to benchmark the current green infrastructure in the region and then identify policies that will allow for stronger and more connected infrastructure networks, more accessibility and cleaner air and water quality.