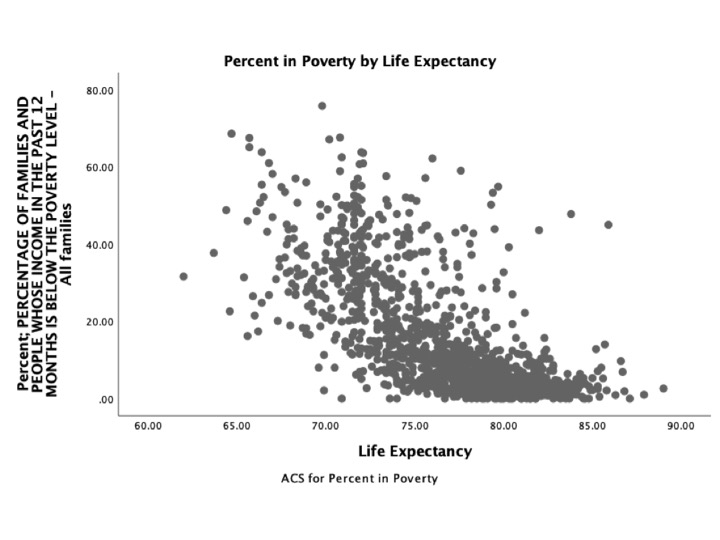

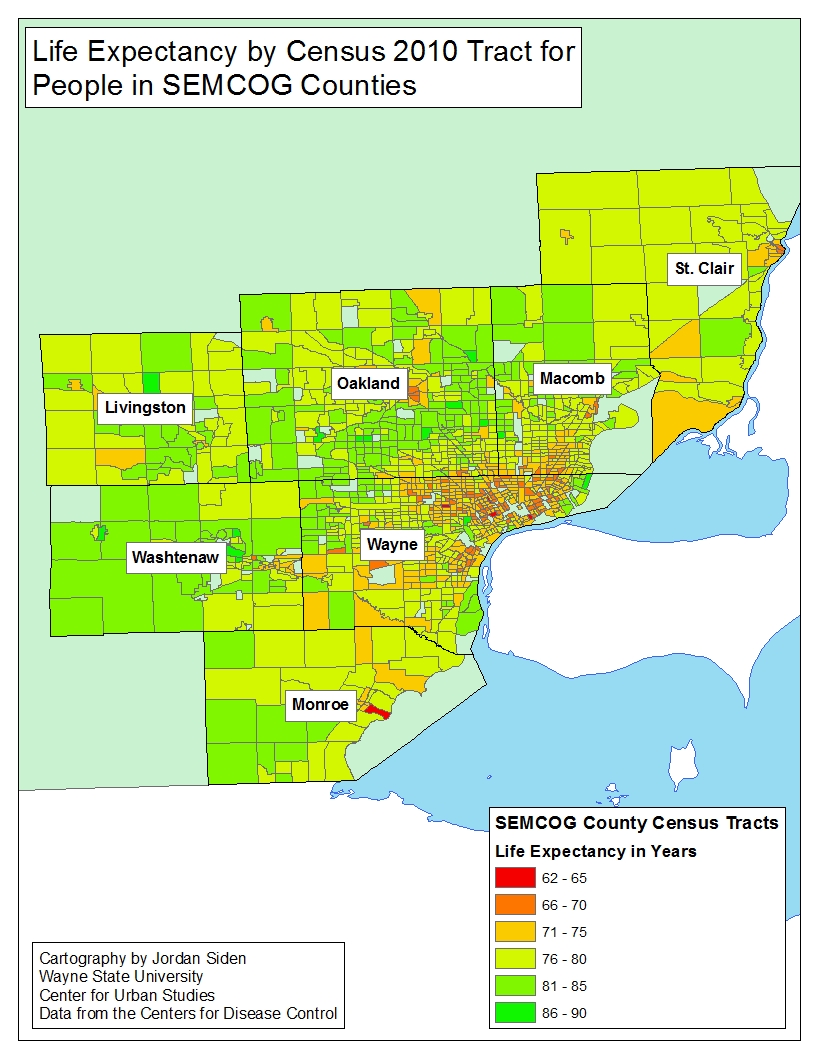

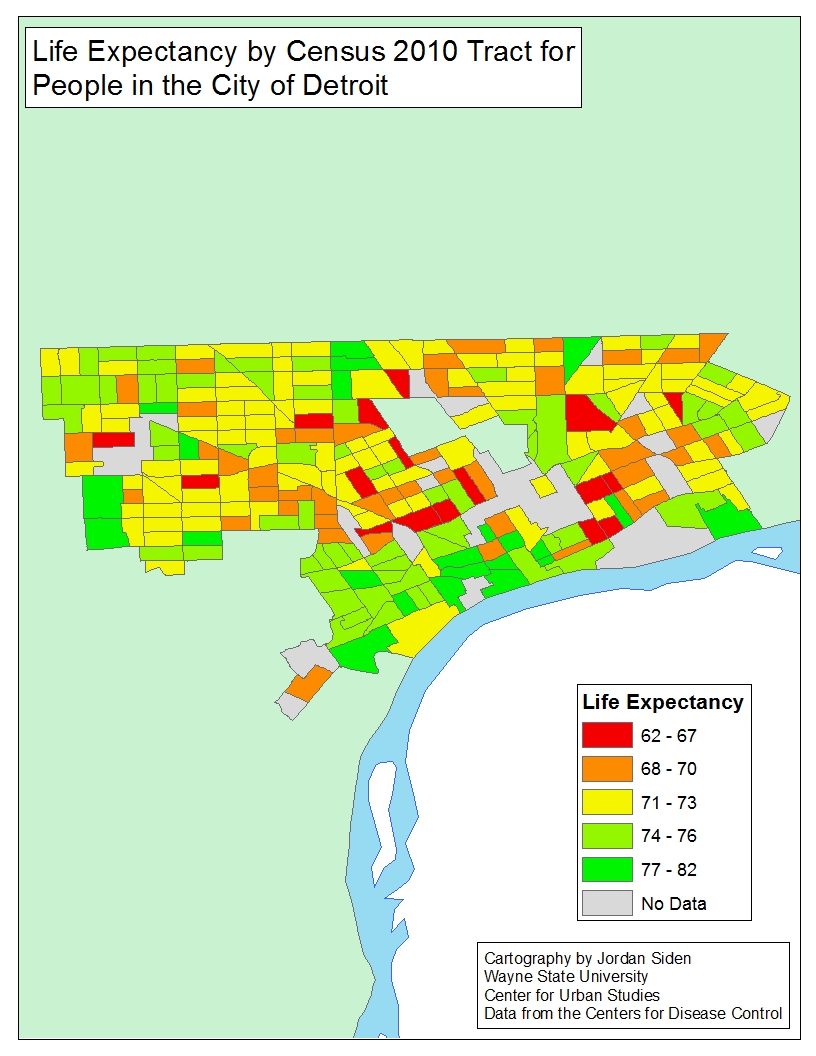

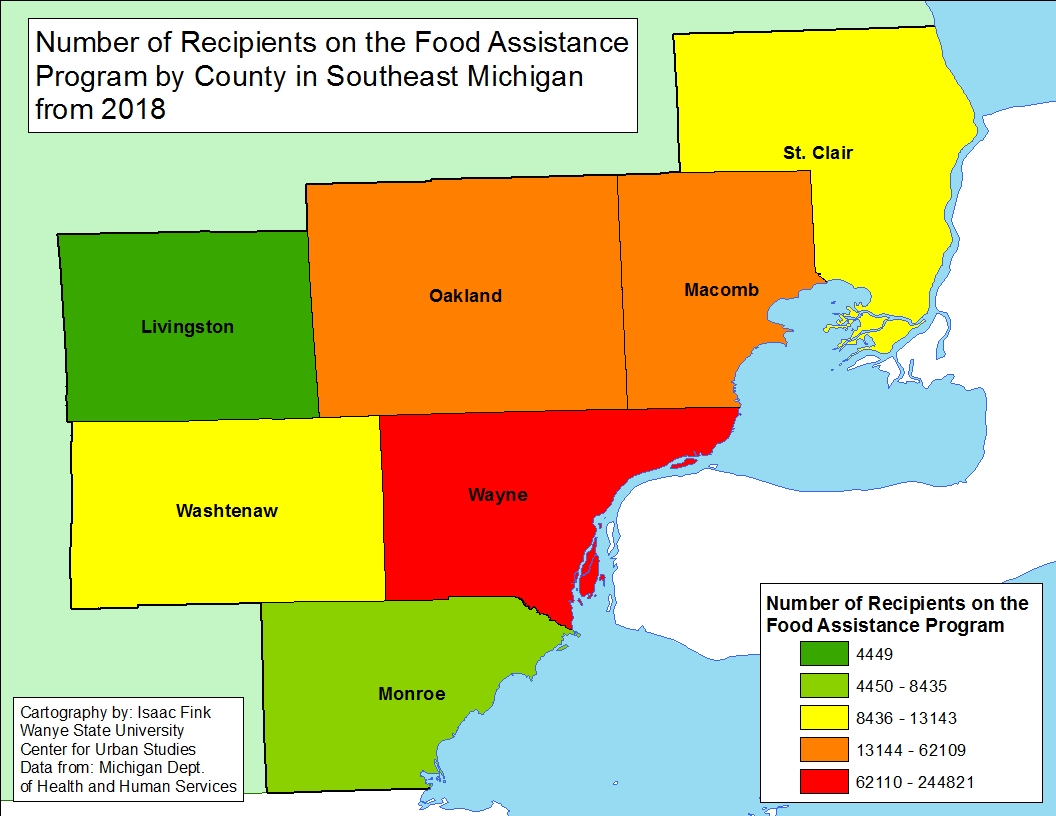

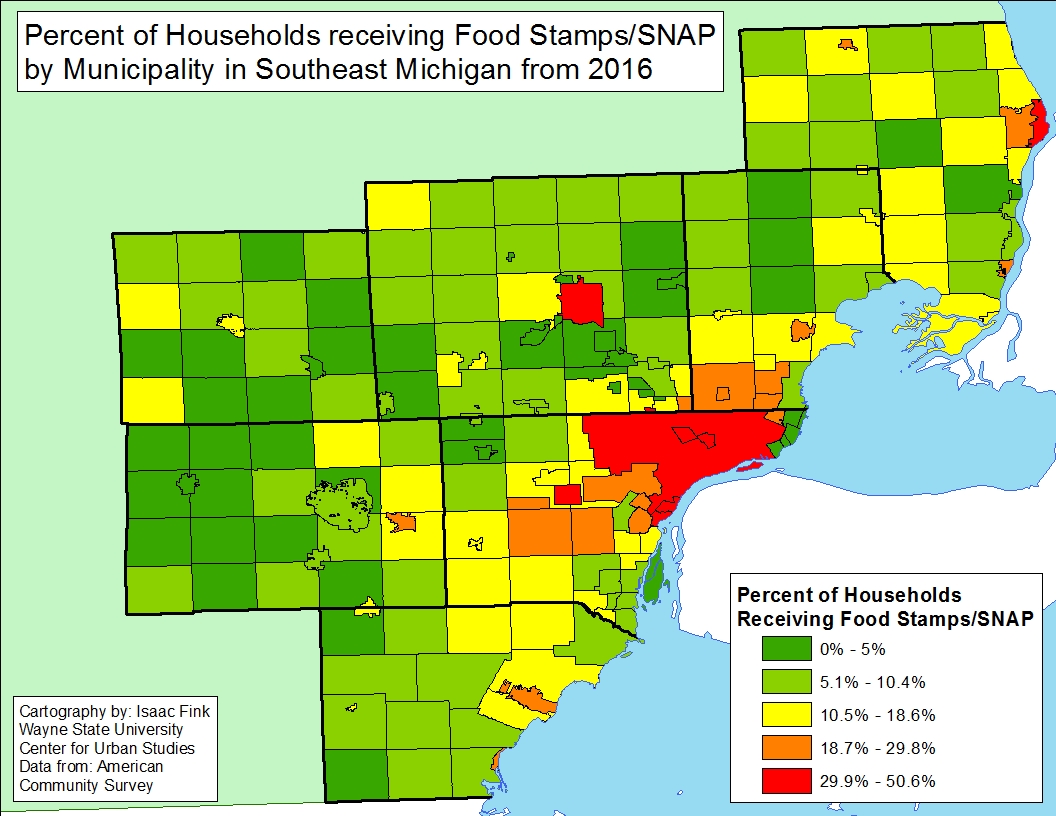

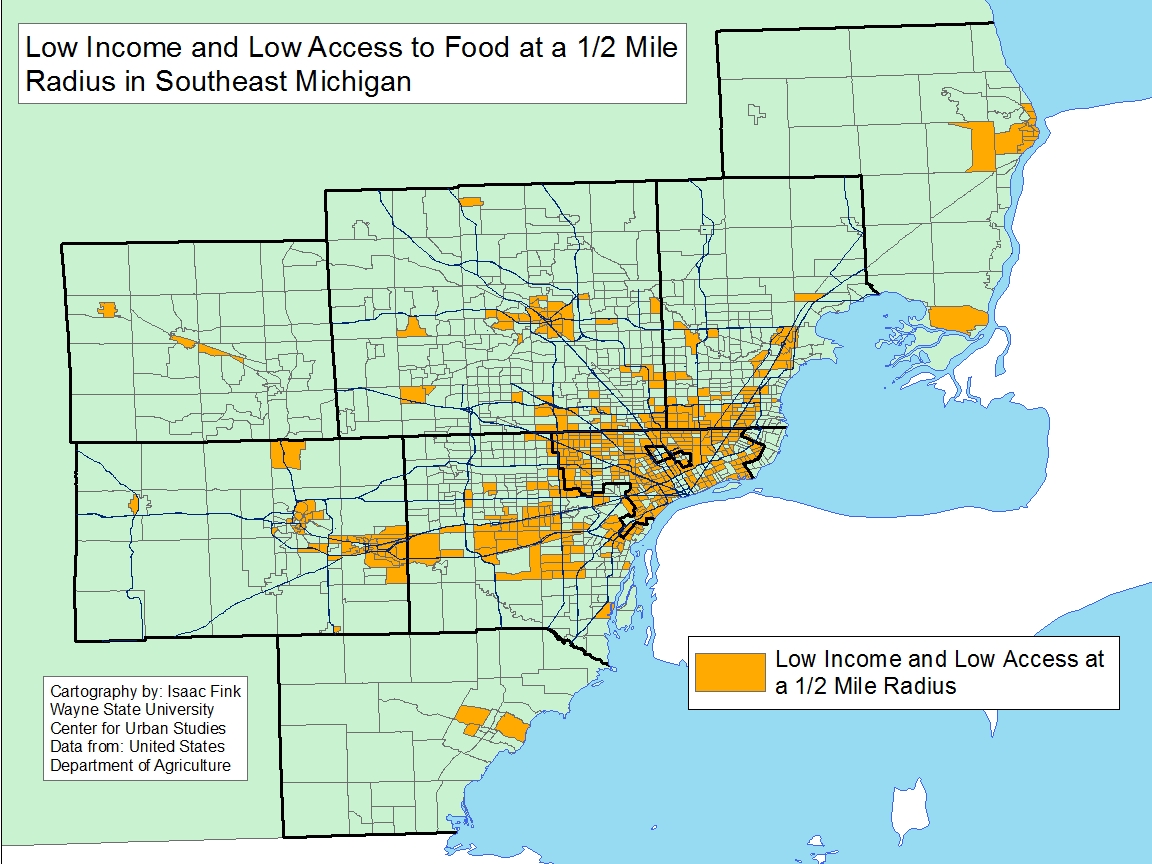

There is a huge variation in life expectancies in Southeastern Michigan, from an average of 62 years in the lowest Census Tract to a high in 85.9 in the highest tract. Moreover life expectancy is closely and negatively related to poverty. The correlation between life expectancy and poverty is -0.713 (sig. 0.01), meaning that there is moderately strong tendency for the length of life to decline as poverty increases in a tract. Or, put simply, poor people die sooner, a lot sooner. Both the maps and chart below present the relationship between shorter life expectancy and poverty or conversely lower levels of poverty in a tract and higher average life expectancy. At the same time, the majority of the areas in Southeastern Michigan have 20 percent or fewer of families living below the poverty line, along with average life expectancies between about 75 and 85 years of age. For reference, the average life expectancy in the United States is about 79 years of age and the federal poverty level for a family of four is $24,300. In 2017 12.7 percent of the U.S. population was living in poverty.

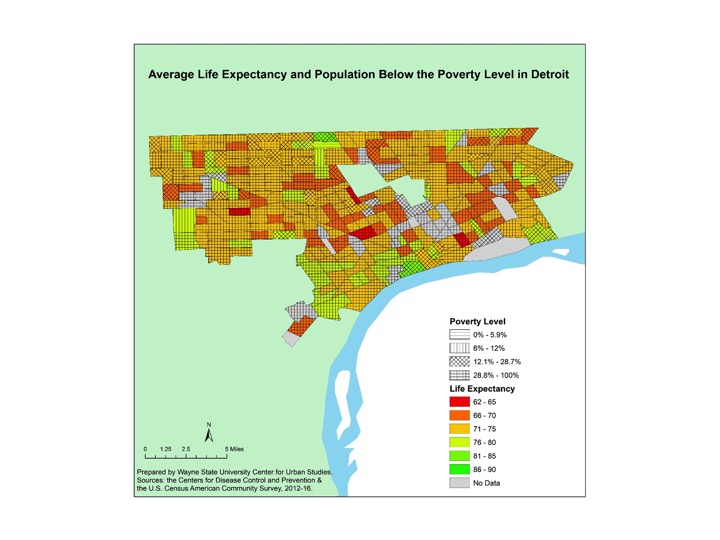

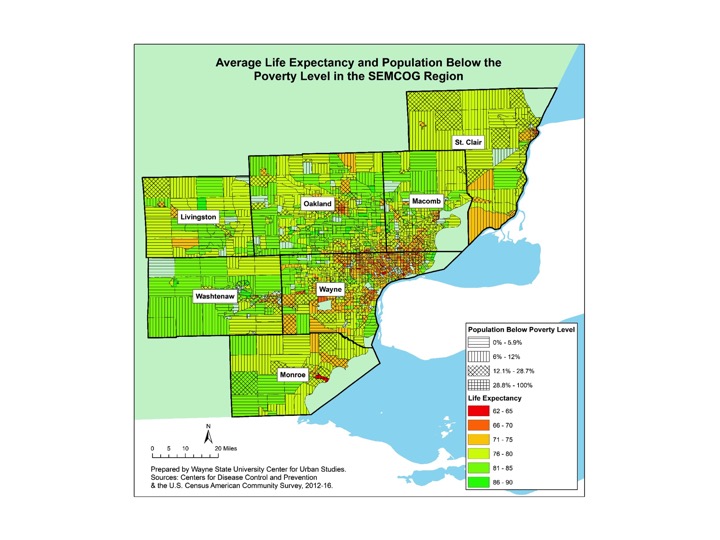

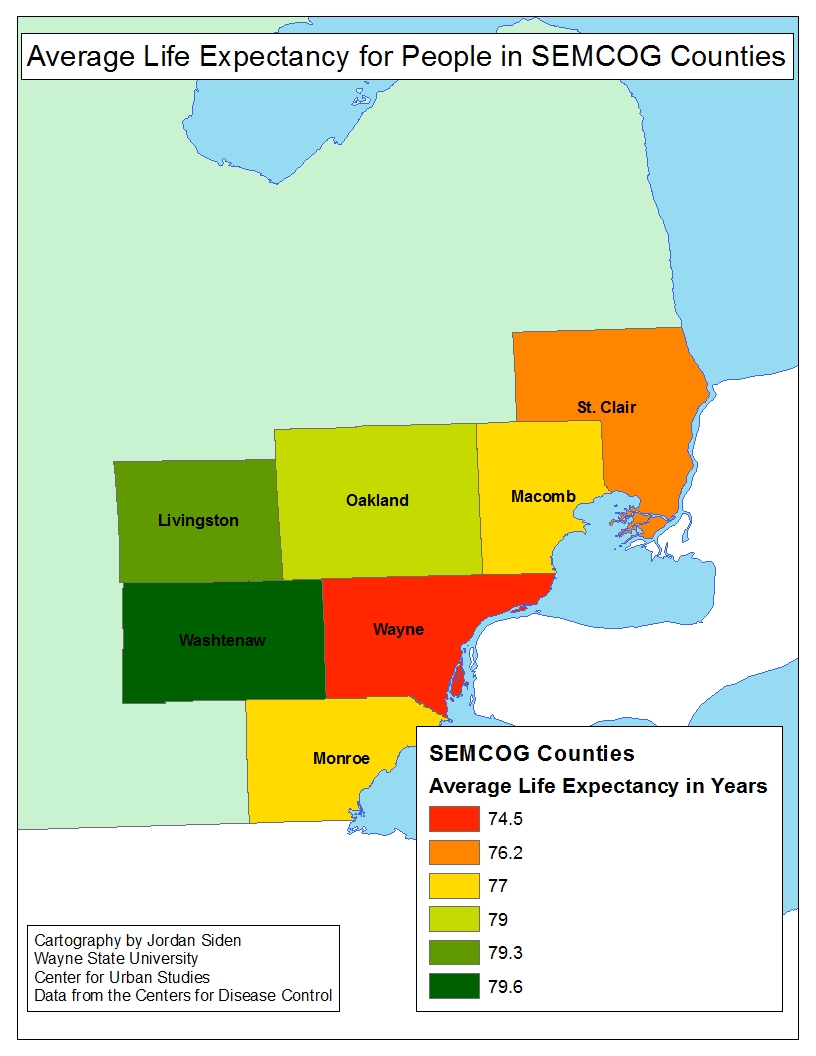

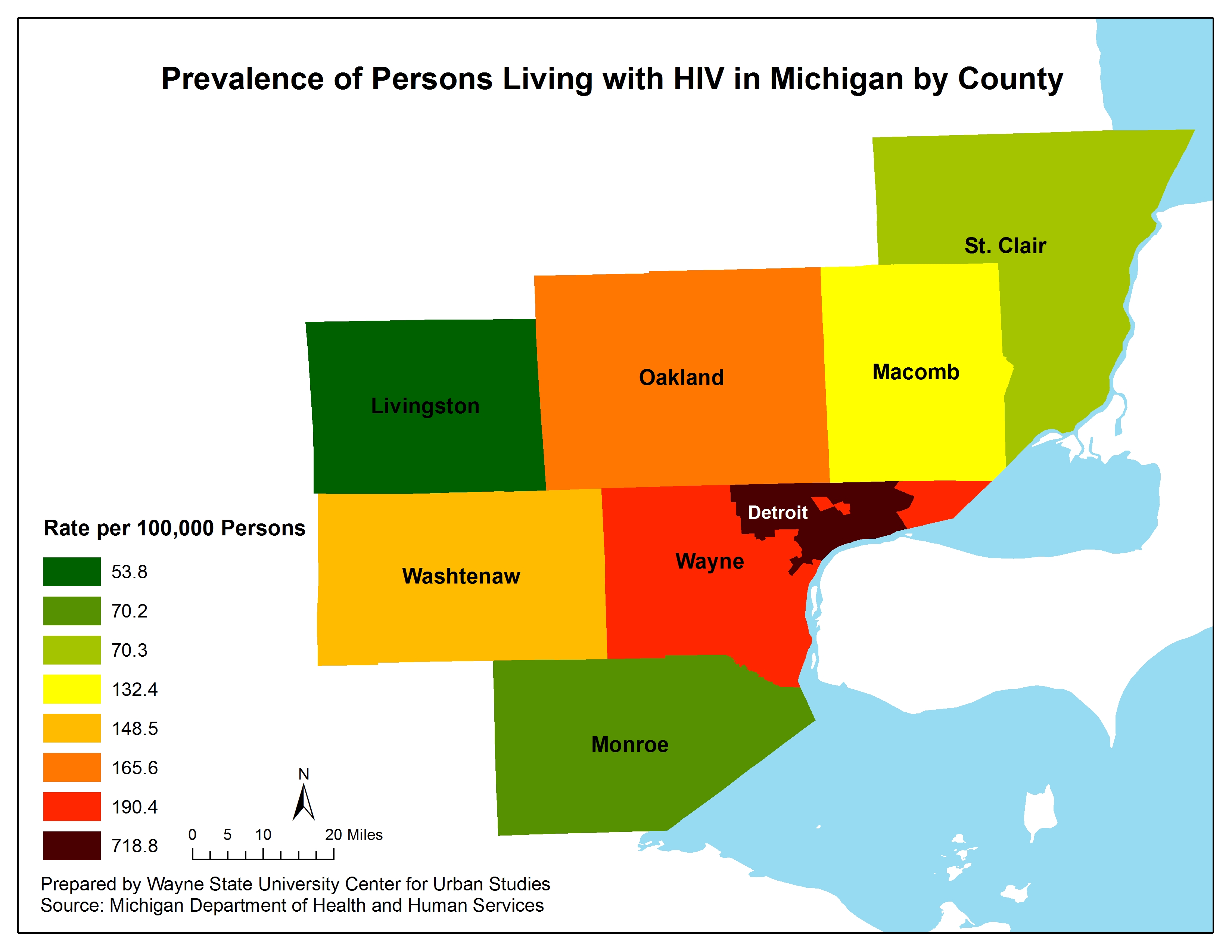

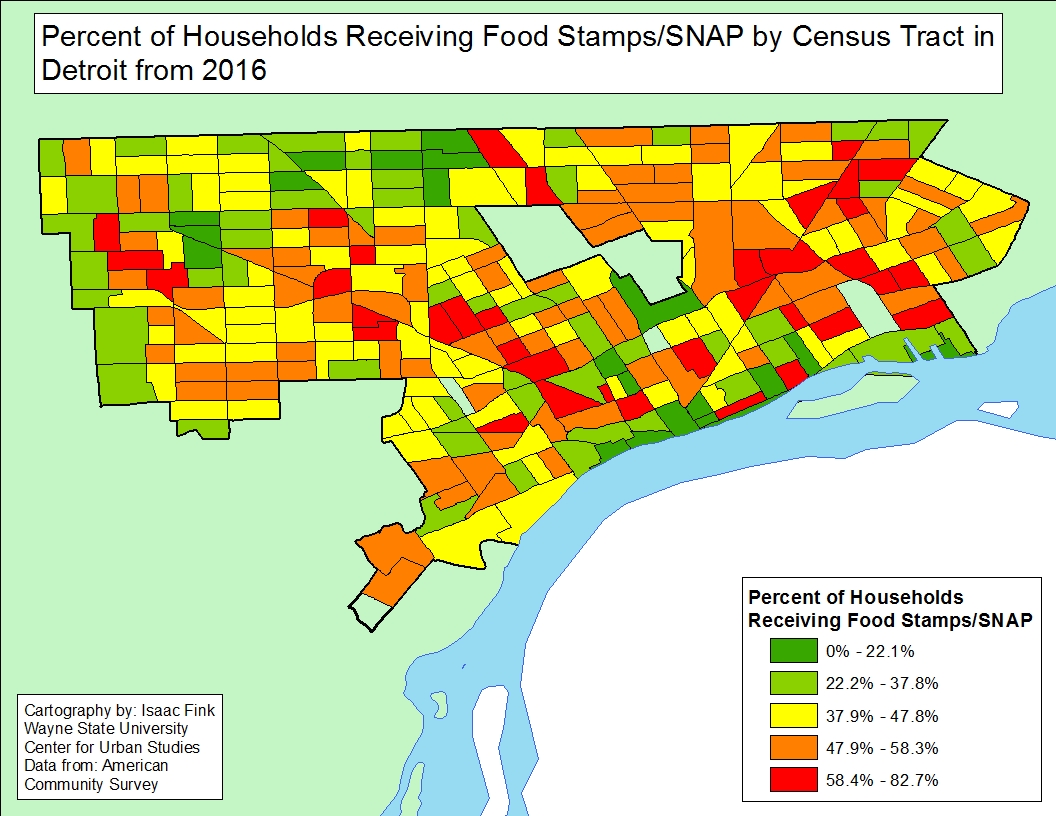

For the City of Detroit there is an average life expectancy across tracts is 71 to 75 years of age, although there are several Census Tracts where the average life expectancy is well below 70. Most of the Census Tracts in Detroit, especially those with lower life expectancies, have more than 28 percent of the population living at or below the poverty line. Specifically, there are three Census Tracts in Detroit where the average life expectancy is between 62 and 65 and the percentage of the population living below the poverty line ranges from about 29-100 percent (the highest threshold in the Detroit map below). While Detroit demonstrates the correlation between higher than average poverty rates and lower life expectancy, there are certain parts of the region where the life expectancy is about on par with the national average (78.8 years of age) but the percentage of the population live in poverty is at or below the national poverty rate (12.7 percent). These examples occur in the mainly the rural areas of the region, such as parts of St. Clair, Livingston and Monroe counties. In general though, radiating out beyond Detroit and the inner-ring suburbs, poverty levels decrease, and the average life expectancy increases. For example, in nearly all of western Washtenaw County the average life expectancy ranges from 81-85 with the poverty levels being at or below 12 percent.

As has been attributed in some of the specific examples noted above, there is a moderately high negative correlation between the percentage of the population living at or below the poverty line and the average life expectancy of Census Tracts in Southeastern Michigan. When looking at the median poverty levels of the region with the life expectancies there is a -0.713 P value, which is statistically significant at the .01 level. What this means is that as the percent in poverty increases, there is a tendency for average life expectancy to decrease.

Overall, these maps show that throughout Southeastern Michigan there is a wide range in life expectancy and poverty levels, with outer ring suburbs faring better and more urban areas, such as Detroit, and some rural areas faring worse. While we see here that poverty does relate to average life expectancy rates, other factors that may also affect average life expectancy include access to health care and educational attainment. The correlation between these factors and the average life expectancy will be explored in the next two posts.