In 2017 the Protecting Local Government Retirement and Benefits Act was passed, with the goal of identifying the systems that are underfunded. According to the State of Michigan, a retirement fund is underfunded if less than 60 percent of the fund is funded, and there is an annual required contribution that is over 10 percent of governmental fund revenues. While 60 percent is the current threshold, there are discussions that eventually that number will continue to increase to 100 percent to more accurately reflect the funded status of a retirement plan. There are also thresholds that determine if a local government entity has an underfunded retiree health care system, an issue we will explore next week.

Currently, in the State of Michigan local government entities are facing, in total, over $18 billion in unfunded liabilities for retirement and retiree healthcare funds, according to the Reason Foundation. This foundation worked with the State of Michigan to develop the Protecting Local Government Retirement and Benefits Act and the reporting system that goes along with it.

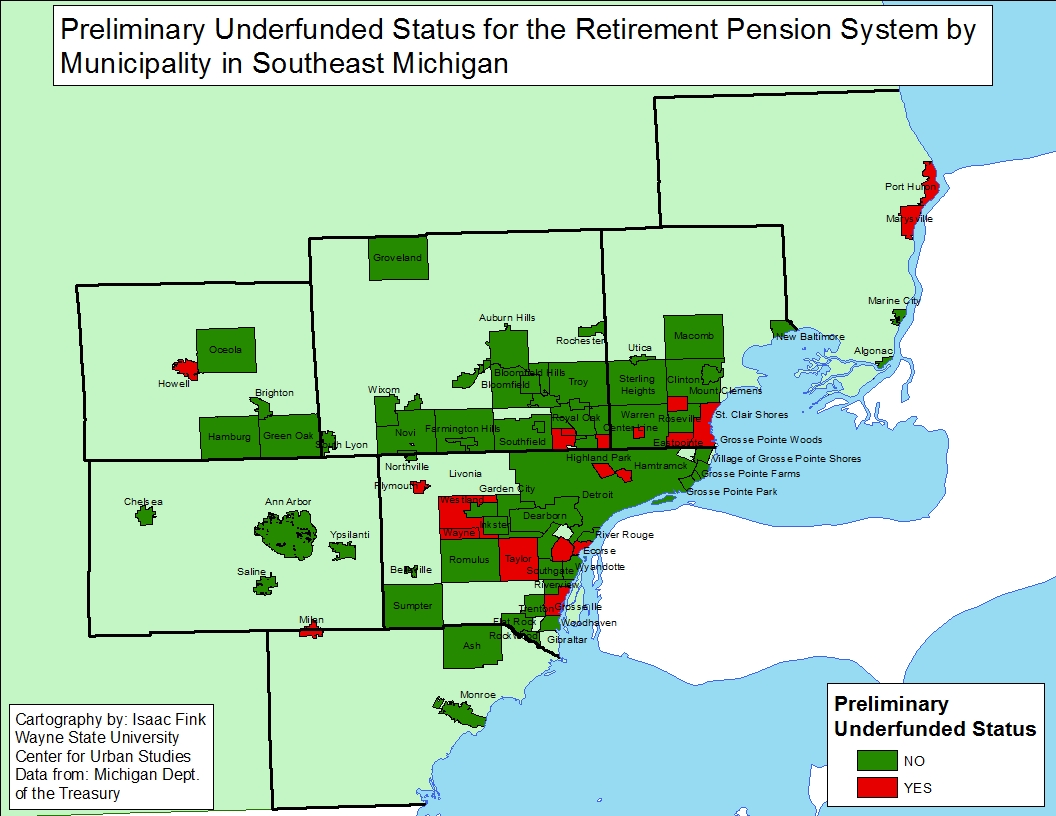

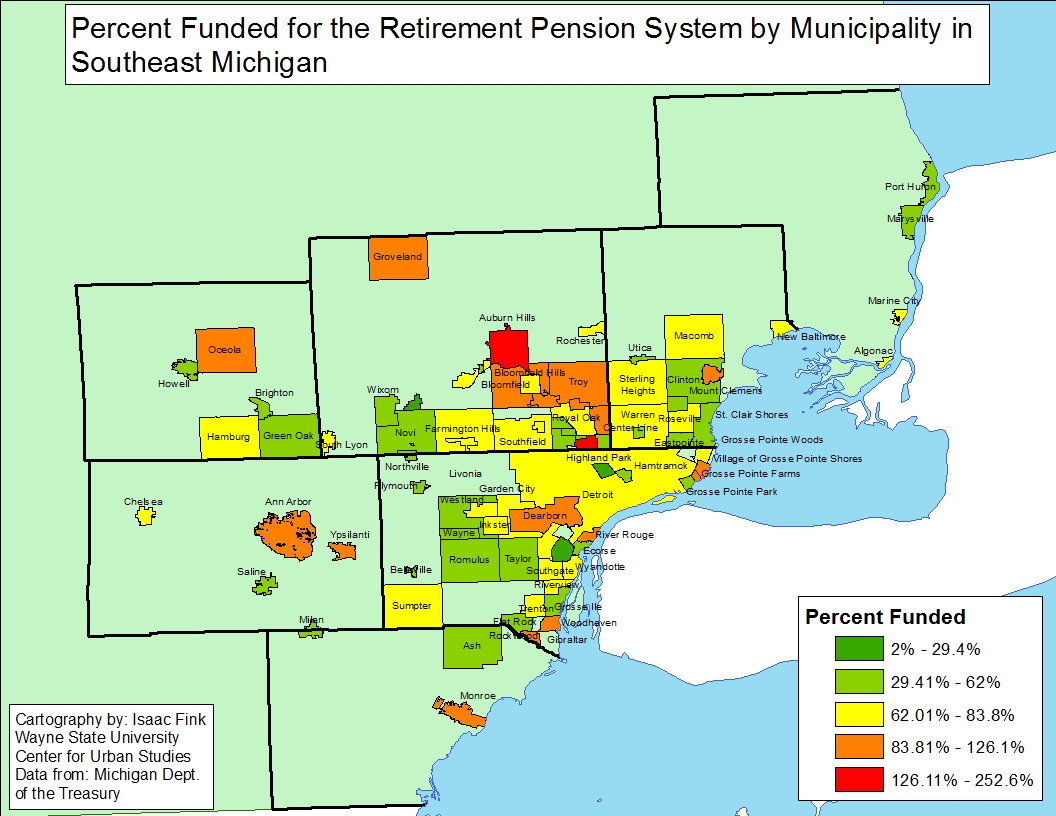

The maps below provide details on what local government retirement plans are preliminary funded or underfunded in Southeastern Michigan, as determined by the Michigan Department of Treasury through implementation of the Protecting Local Government Retirement and Benefits Act. These are deemed preliminary due to the fact the new oversight body for determining funded, unfunded and waiver status must still review information submitted. Note, information is not displayed for all local government units in the region because not all units had provided their funding as of June 9, 2018. Additionally, some local government units beyond cities and townships are included in the data provided by the State, such as public safety retirement funds.

Of the 183 local government entities (this includes multiple funds for one municipality) that submitted their retirement funding information to the State for the Southeastern Michigan region, 37 of them were reported as having an underfunded status, or less than 60 percent of the retirement fund being funded. Of those that were reported as being underfunded, the majority of them had 45 percent or more the entity’s retirement system funded. However, there were five entities with 25 percent or less of the retirement system funded. These entities were:

- Capac (St. Clair County): 24.2%

- Highland Park General Employee fund: 2%

- Highland Park Public Safety Fund: 3.7%

- Highland Park Police and Fire Fund: 6.8%

- Taylor City Housing Commission Authority: 0%

It should be noted that while the City of Taylor’s Housing Commission Authority retirement fund is underfunded, the City of Taylor’s general employee and police and fire retirement funds met State guidelines to be determined funded.

As part of the newly adopted State legislation related to retirement and retiree health care plans a Municipal Stability Board was created to review the corrective plans that underfunded entities must create and submit to the State. This board is housed under the Michigan Department of Treasury is made up of three individuals appointed by the governor. Corrective plans must be developed and submitted within 180 days of the State determining an entity’s retirement system is underfunded.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, while there were far more local government entities that were determined have funded retirement systems, than not, there were several that were more than 100 percent funded. The entities with the highest percentage of funding for their retirement funds were:

- City of Ferndale (General Employees): 253%

- City of Dearborn (Chapter 24): 239%

- City of Pontiac (General Employees); 176%

- City of Ypsilanti (General Employees) 126%

- City of Grosse Pointe: 119%

- City of Troy: 117%

- Lima Township: 112%

- City of Grosse Pointe Farms: 111%

- City of Gibraltar (General Employees): 106%

- City of Dearborn (General Employees): 104.3%

- City of Mt. Clemens: 103%

- Oakland County: 103%

- City of Gibraltar (Public Safety): 102%

- Groveland Township: 101%

Funding of retirement plans is vital for all local government entities as underfunded plans can lead to long-term financial troubles for a government entity, not excluding bankruptcy. Additionally, underfunded plans can also affect recruitment and retention of employees.