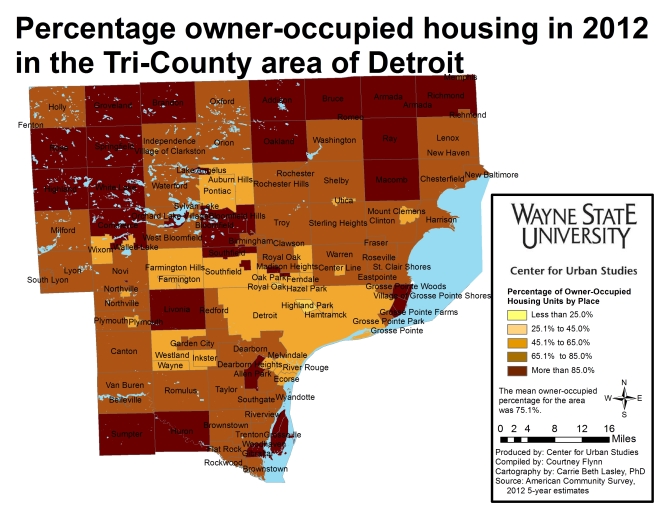

Detroit has embarked on one of the largest scattered site demolition projects in the world. This task is reflective of the city’s vacancy rate, which is considered one the highest in the nation (Kolko, 2013). Property values are still on the decline in Detroit, as can be seen by a more than 10 percent decrease in the city’s state equalized value (SEV) in the past year (Liu, 2014). Property values are very sensitive to such vacancies, impacting the potential for revenue generation in a city just emerging from bankruptcy. Thus, the blight demolition projects have taken center stage as the city tries to revitalize itself. Here we take a closer look at the various sources of statistics that show discrepancies in just how many structures are considered blighted and ready for demolition. We consider the policies surrounding this issue.

The first step to determining how many, and which, houses to tear down includes a complete inventory of the residential structures within the city, including an analysis of how many of those are vacant. For those structures that are determined vacant, it must then be determined how many are in such a state of disrepair and decay that they are unlikely to attract interest from someone willing to renovate and move in.

There are stark differences in the extimates of the number of vacant homes. Data Driven Detroit’s Motor City Mapping project (www.motorcitymapping.com), deployed over 100 data collectors throughout the city to survey every city lot and to rate the condition of the remaining structures including vacancy and fire damage. They identified 261,275 total structures in Detroit in 2013, and identified 48,327 as unoccupied, for a vacancy rate of 18.5 percent.[i] In 2012, which is the most recent data, the American Community Survey for the U.S. Census Bureau, estimated in its 5-year estimates that 104,143 of 363,010 housing units (not just structures) were vacant, for a rate of 28.7 percent. The Blight Removal Task Force, which was formed by the Obama administration in 2013 to recommend a course to deal with the massive amount of blight in Detroit, estimated that Detroit had 78,506 vacant structures of 380,000 for a rate of 20.7 percent; this data was collected from December 2013 to January 2014. Additionally, the U.S. Postal Service recognized 87,731 vacant addresses out of 363,045 for a rate of 21.6 percent in December of 2013. Below is a table that summarizes these figures:

|

Data Driven Detroit

(2013) |

Blight Removal Task Force

(2013) |

USPS

(2013) |

American Community Survey (5 yr estimate 2012) |

Total Average |

| Detroit Vacancy Rate

|

18.5 |

20.7 |

21.6 |

28.7 |

22.5 |

The estimates of the number of structures that should be removed is just as variable. The Motor City Mapping platform states that the need for two major repairs results in the structure as being deemed in “poor condition.” For a structure to be deemed for “suggested demolition” by Motor City Mapping it must “not appear to be structurally sound, may pose safety risks, and is generally uninhabitable. The building may be buckling, caved in, or otherwise severely compromised.” With this definition, Motor City Mapping determined 4,431 properties were rated for demolition, a rate of 1.7 percent of structures. In the same study, Motor City Mapping indicated that 6,873 structures, or 2.6 percent, had fire damage in 2013; 5,979 (2.3 percent) had become obvious dumping sites and that 27,640 (10.6 percent) structures needed boarding from intruders and the elements. By contrast, the Blight Removal Task Force recommended 40,777 structures for immediate removal, or 10.7 percent of the housing stock. The task force determines if a structure should be removed if it meets the definition of blight and where the estimated cost of rehabilitation (to code) will exceed market value or create positive economic opportunities for the neighborhood,” (Detroit Blight Removal Task Force Plan, pg.125). The Detroit Blight Task Force considers a property blighted if it is: a public and/or attractive nuisance; fire damaged or otherwise dangerous; has code violations posing a severe or immediate health or safety threat; is open to the elements and trespassing; is already on the city of Detroit’s demolition list; is owned or under the control of the land bank; has had utilities, plumbing, heating or sewage disconnected, destroyed, removed, or is otherwise ineffective; is a tax reverted property; has been vacant for five consecutive years and is not maintained to code (timetoendblight.com).

|

Data Driven Detroit |

Blight Removal Task Force |

| Recommended for demolition in 2014 |

4,431 |

40,777 |

| Percent of housing stock |

1.7% |

10.7% |

According to the federal, state and city government, removing these structures is essential for “neighborhood stabilization” (City of Detroit Planning and Development Department 2011, Michigan Foreclosure Task Force 2013, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2010). Demolition of of several thousand homes will be completed through the use of $52.3 million in Hardest Hit Funding. These funds, allocated by the U.S. Treasury from the Troubled Assessed Relief Problems (TARP) funds for those states hardest hit by the mortgage foreclosure crisis, must be spent by April 30, 2015 or it will be lost (Detroit Building Authority 2014). An additional investment of approximately $250 million may be awarded toward the same goal in a short period. While each state helps to tailor the local allocation of Hardest Hit Funding, most communities in Michigan and other states have elected programs that help homeowners facing foreclosure to make payments while they look for work (U.S. Department of Treasury, 2013). Other uses of this funding, besides demolitions, include property auctions and loans for renovation. More information about these programs can be found at www.buildingdetroit.com.

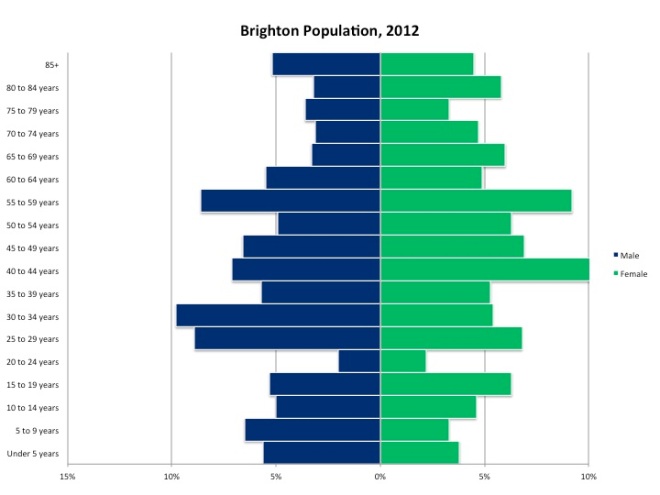

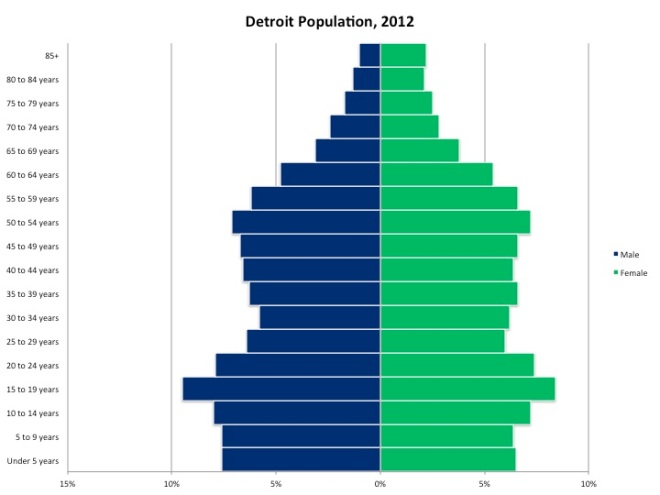

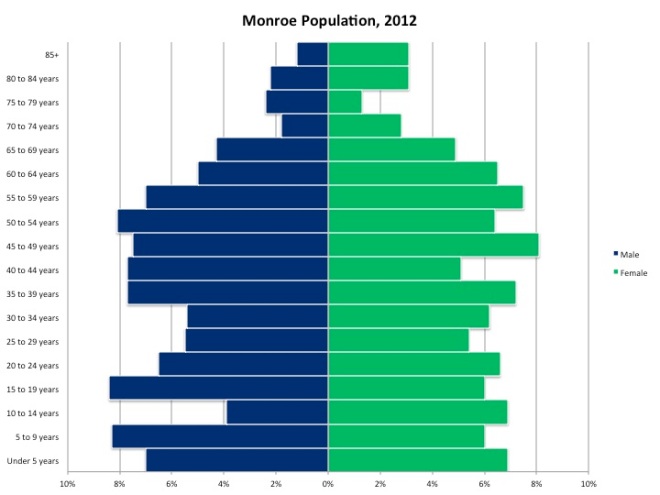

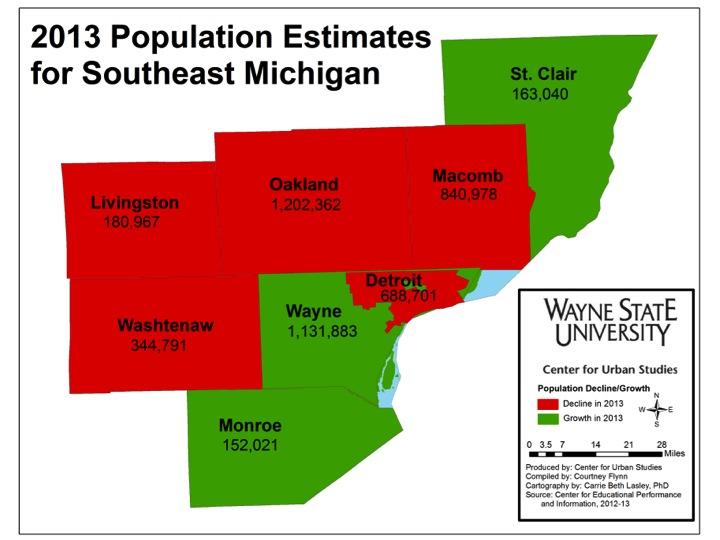

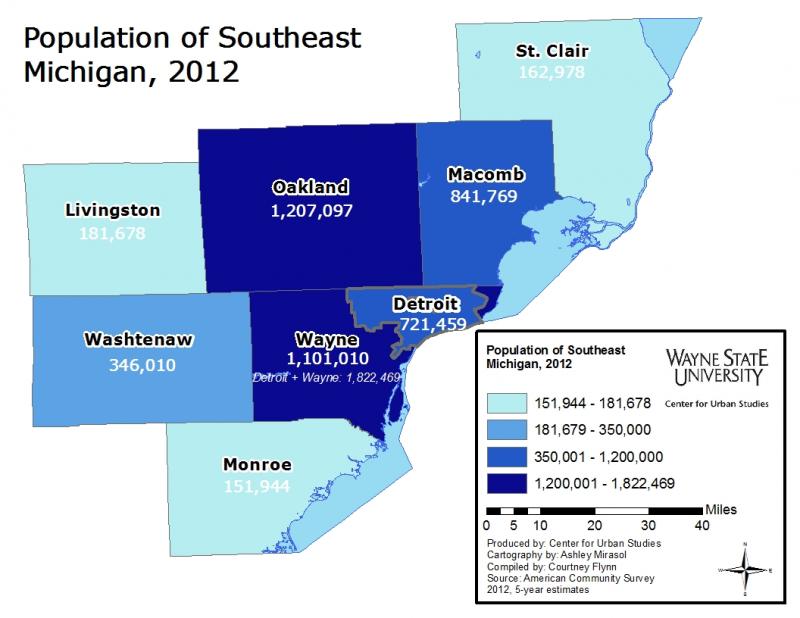

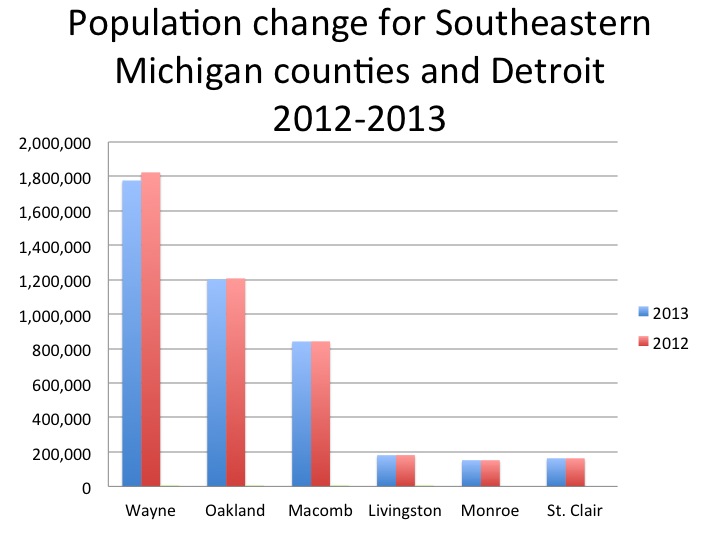

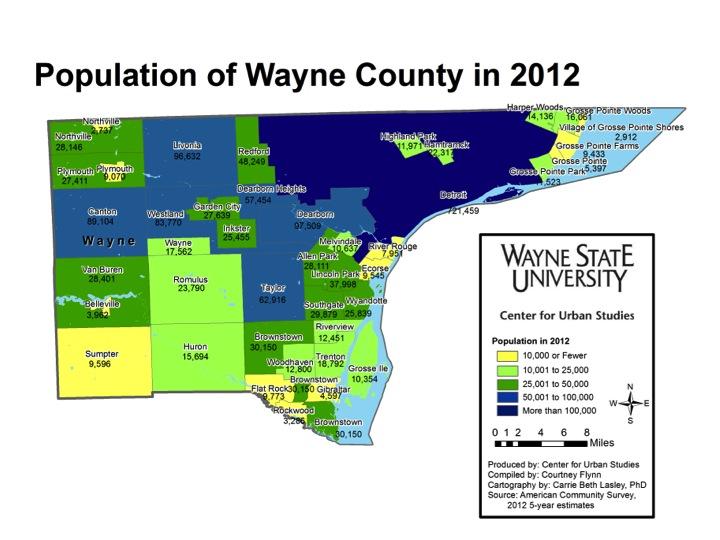

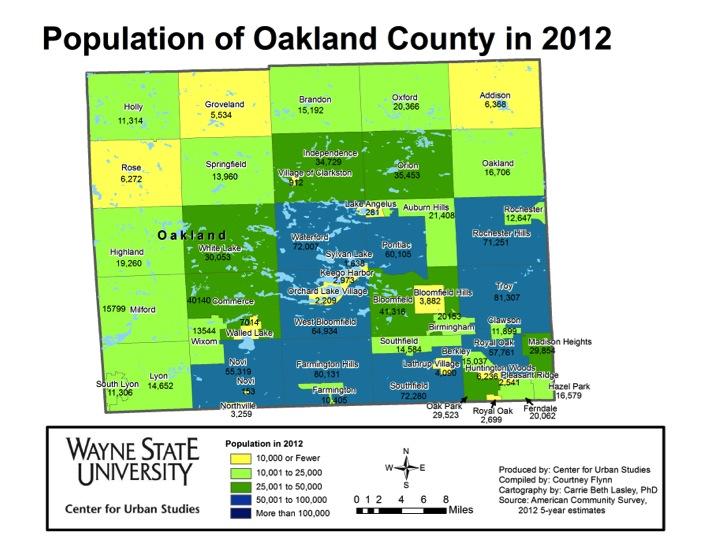

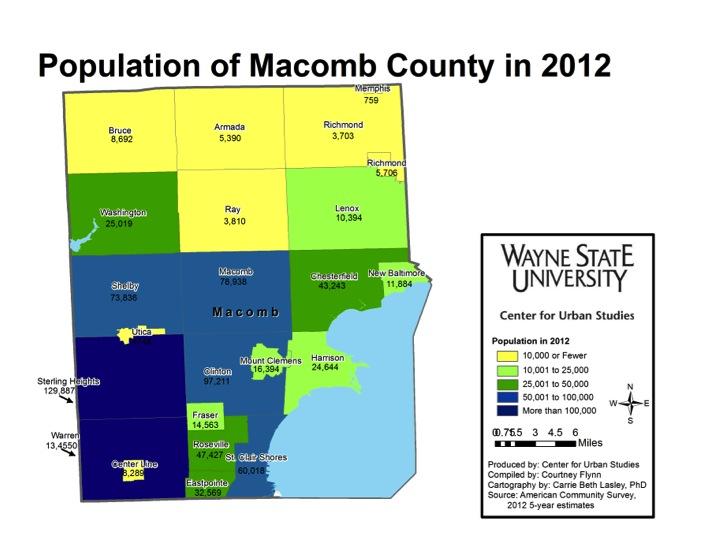

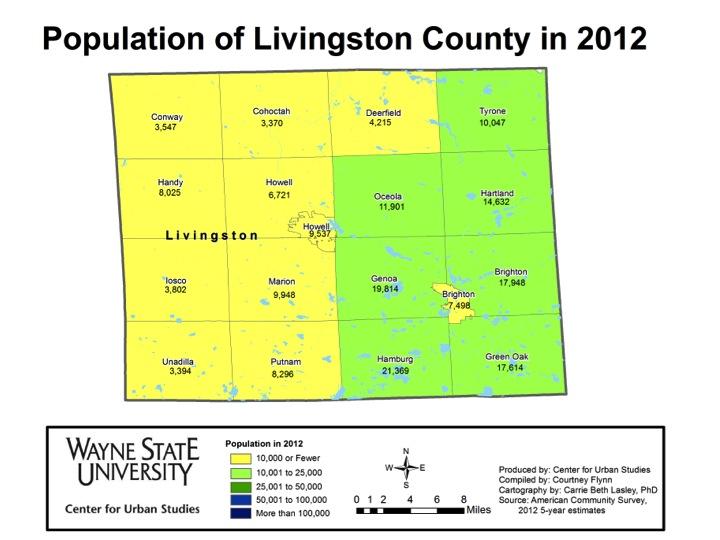

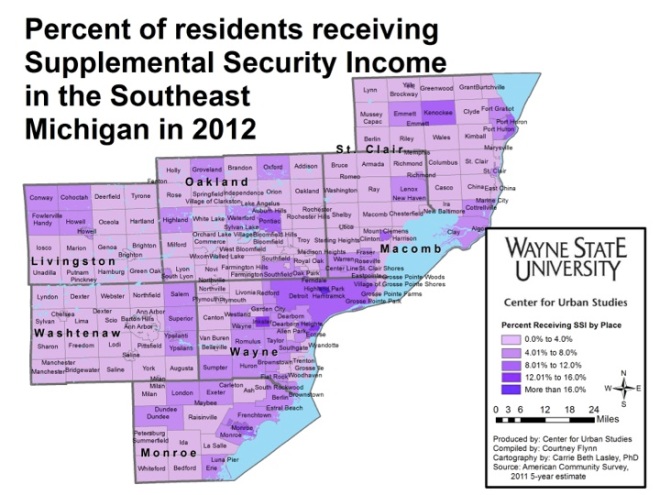

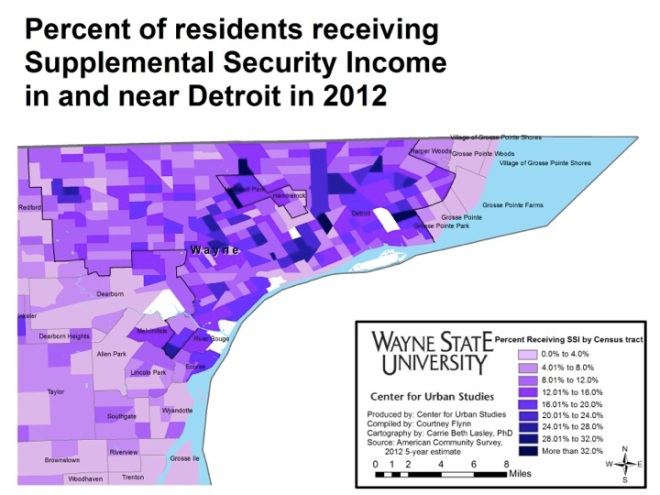

While the decision-makers engaged in this process appear unified on the need to use demolition to spur redevelopment, these decisions are being made in an unstable urban environment. In the short run population is still in decline, having not yet reached its nadir. Nearly 120,000 residents have left Detroit since 2008 (U.S. Census Bureau 2014). As Detroit’s population dwindles homes likely will continue to be left vacant, as the number of people moving back to Detroit is unlikely to come close to equaling the number of those who have left.

High-profile urban institutes, including the Brookings Institute, have identified Detroit’s vacant homes as an economic handicap, citing the need for demolition to equalize supply and demand in the housing market and thus stabilize property values; to resolve expensive nuisance issues related to maintaining abandoned properties; and to reduce disincentives to revitalization (Mallach 2012). Other potential benefits of a demolition policy include removal of sites of criminal activity and removal of pests such as rats, roaches and stray animals (Detroit Blight Removal Task Force Plan 2014, Institute of Population Health 2014).

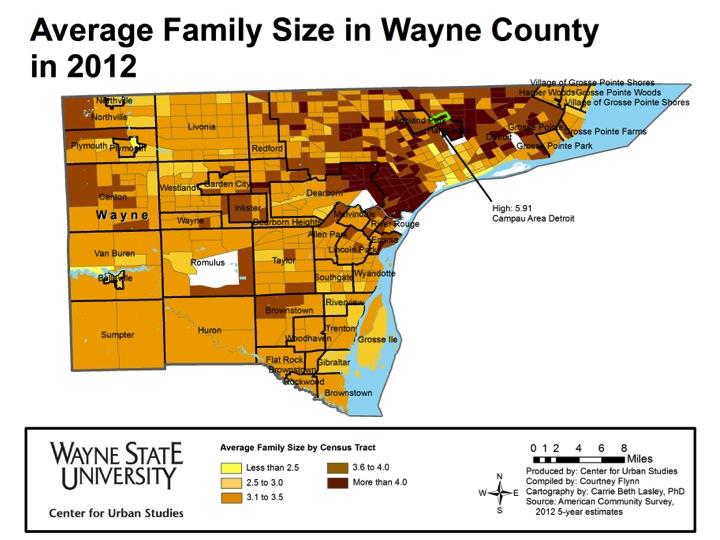

However there are major potential downsides to this massive program of demolition. The large-scale demolition in a small area of Detroit in a short time is likely to exacerbate health problems that may be unconcerning for a single demolition. This is the case according to the Blight Removal Task Force’s own plan as well as the Health Impact Assessment funded by the National Association of County and City Health Officials and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Health Initiative (Detroit Blight Removal Task Force Plan 2014, Institute of Population Health 2014). Lead and other heavy metals and toxic chemicals from the demolition will create toxic dust and aerosols that may impact neighbors by causing or triggering conditions such as lead poisoning or asthma. Lead can be ingested through dust and can also contaminate soil, especially around older buildings with flaking external paintwork, or near industrial buildings. The most prevalent risk from lead exposure is IQ deficiency in children – even with relatively low lead levels in blood, there are indications it negatively affects children’s IQ. The most vulnerable age group is children under 3 years old because of potential effects on neurological development, and because young children’s bodies more readily take up lead. Other risk groups include pregnant women and fetuses. For asthma, which is a chronic disease characterized by the swelling and narrowing of the airways to the lungs, it can be triggered by, dust, mold and volatile organic compounds (among other things), which have the potential to be emitted into the environment following demolitions. Those who experience symptoms of asthma often wheeze, have shortness of breath, a sensation of a tight chest, and cough.

In addition to the potential health risks related to mass demolitions, there is also no guarantee that if you demolish a structure, a new home will take its place. After the building has been removed, there are limited investment incentives currently in place to encourage investors to redevelop these vacant parcels, leaving the city pocked with large swaths of vacant and open land between homes in some areas. Aside from the Detroit Land Bank, where structures and vacant lands in the city are auctioned off, land will be city-owned, meaning maintenance of these vacant parcels will be the obligation of the city. This has caused problems historically for other cities, especially financially insecure cities like Detroit. After Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans and neighboring communities that lost significant tax bases encountered similar issues of having a substantial number of abandoned properties turned over to the municipality. The problem became how to redistribute this property to other agencies or investors to reduce the maintenance burden on a city incapable of significantly expanding its staff to meet the maintenance needs.

What would be an improvement is a strategy that reduces demolitions, while tightening the dust suppression by implementing protocols similar to those in Baltimore that call for increased deconstruction and the use of temporary barriers during demolition. This would cost more, but reduce the consequences for this generation of Detroit’s children.

In addition, more housing should be boarded so it could be rehabilitated as the city’s housing market improves. Third, housing rehabilitation should be targeted for neighborhoods that are already starting to improve as directed patrol, CompStat and other public safety interventions reduce crime and increase public safety. Within these targeted neighborhoods, home improvement would targeted around schools where safe routes have been established and educational improvement is underway. Together these measures are likely to produce an improving market as we are beginning to see in Midtown, North End, Corktown and along some stretches of East Jefferson.

[i] This is an on-going endeavor. Right now DDD is deploying data gatherers to update its data in several neighborhoods where change is particularly fast.