Michigan’s charter school system is widely becoming known as a for-profit business venture as well as another option for students to receive high quality education. With over 30 charter school authorizers and management companies throughout the state of Michigan, there is no question that the choice to send students to charter schools is there. However, there are questions over whether or not the academic foundations students need to in order to become successful are also there.

This is a two part post, and this week we will lay the foundation on charter schools in Southeastern Michigan, by showing where they were located in the 2013-14 academic year and detailing where and why others closed. Next week we will look further into the overall academic progress of some of Michigan’s charter school authorizers.

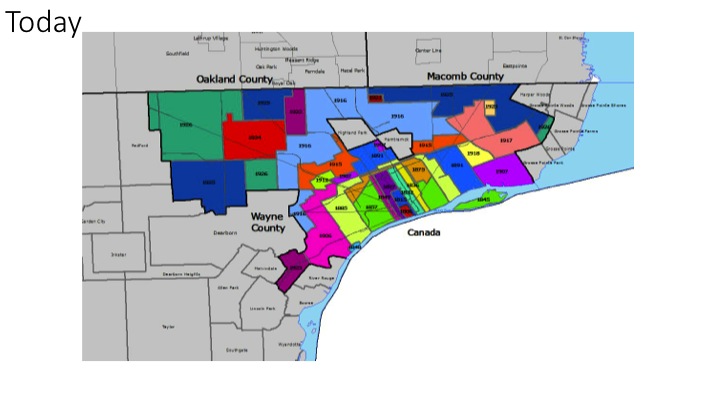

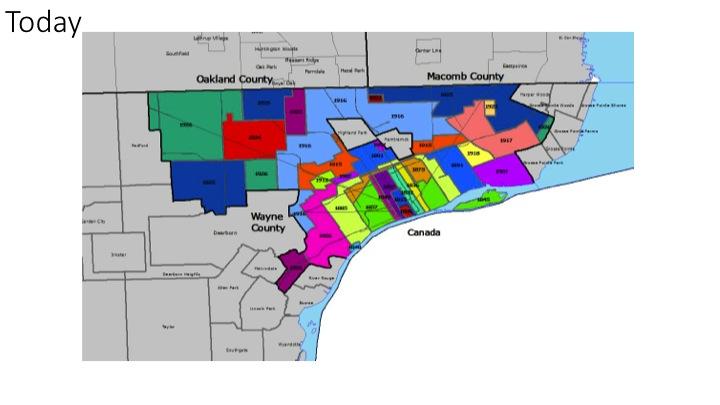

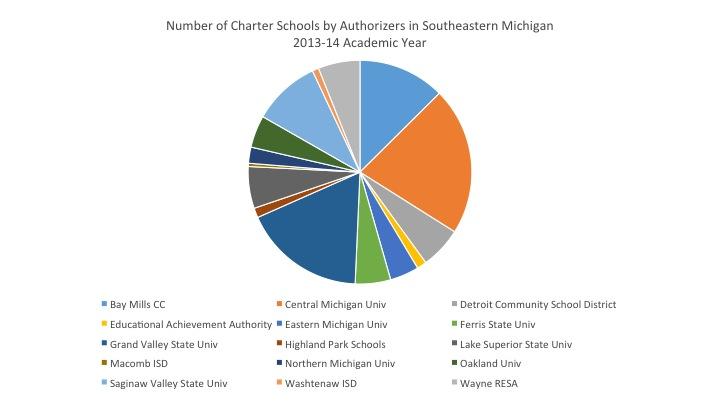

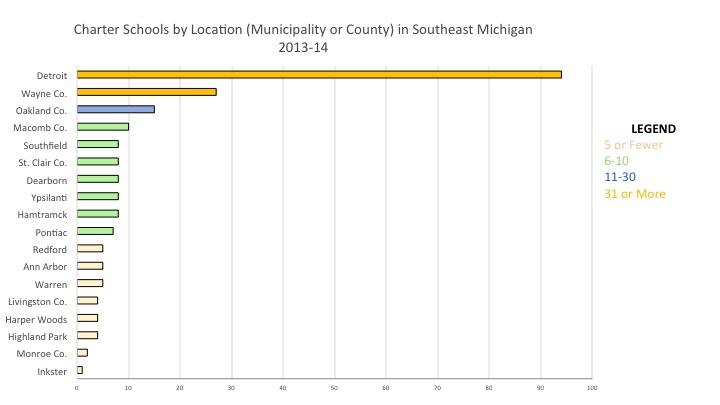

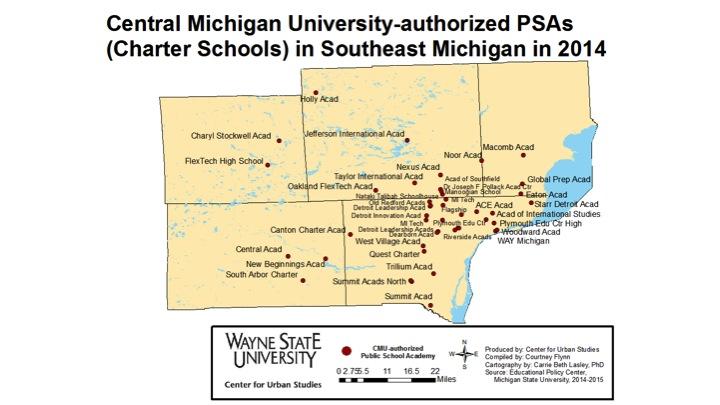

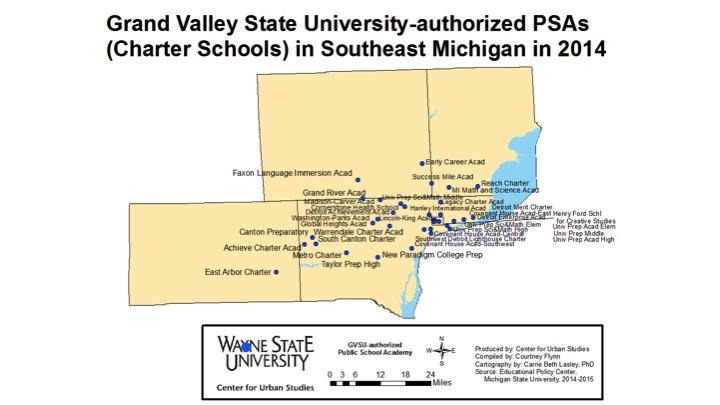

Of the 298 charter schools in Michigan during the 2013-14 academic school year. In total, there were 223 charter schools in the region during the 2013-14 school year. Of all the charters in the state, 31.5 percent (94 schools) were located in the city of Detroit, according to information from the State of Michigan and the Michigan Association of Public School Academies. Within Detroit itself, the majority of these schools were authorized by Grand Valley State University. Throughout the state of Michigan, the most common charter school authorizers are universities; regionally Central Michigan University operates the largest number of charter schools. As the oldest charter school authorizer in the state, CMU oversaw 46 charter schools in 2013-14, according to Michigan’s Charter School Authorizer Report from November 2014. Grand Valley State University had the second highest number at 38.

It wasn’t until 2012, the year following the state’s decision to remove the cap on the number of charter schools a university could authorize was removed, when several local school districts, intermediate school districts and community colleges also opened charter schools, according to Michigan’s Charter School Authorizer Report.

The for-profit and non-profit organizations that operate charter schools are known as Education Management Organizations (EMOs). Although exact information on the number of charter school management companies for the 2013-14 school year wasn’t available, we do know that there were more than 35 during the 2011-12 academic year, according to a 2013 report (link) by the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado. In this report, it states that Michigan had 33 for-profit EMOs operating charter schools, which operated 79 percent of Michigan’s charter schools. Non-profit organizations can also manage schools, as can the authorizers themselves. In July of 2014, former Michigan State Superintendent Mike Flanagan took a stance against charter school authorizers, stating he would exercise his authority to suspend them if they did not live up to the mission originally intended for charter schools, which is “to provide high quality education options and cultivate better outcomes, especially for low income children.”

Flanagan’s statement against charter school authorizers was prompted by the 2014 Detroit Free Press series that took a look at the state’s charter school authorizers, management companies and the way in which both utilize public tax dollars and educate children. The series showed that charter schools lack accountability, despite their use of public funds. This series was published following the 2012-13 academic year, and this post reflects on data from the 2013-14 academic year. However, the Free Press series was used for background purpose.

Below is a breakdown of the number of charter school authorizers in the region for the 2013-14.

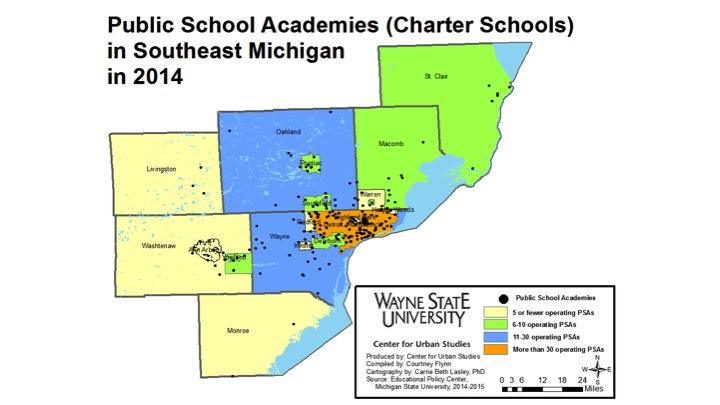

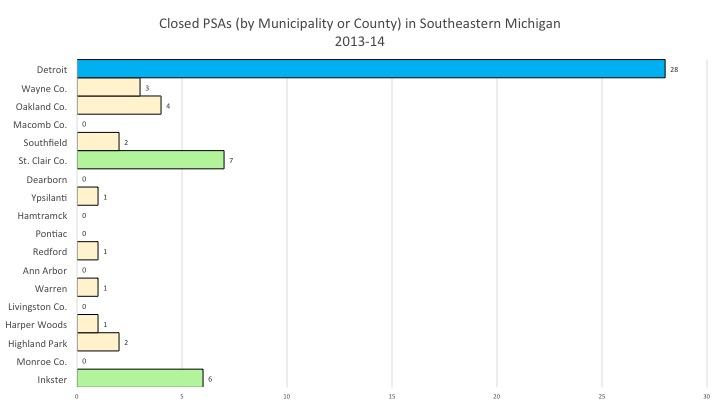

As noted, in Southeastern Michigan, the city of Detroit had the highest concentration of charter schools, with 94 (31.5%) operating in the city during the 2013-14 academic year. That year, 24 charter schools closed in Detroit, the highest number for any municipality in the state. Overall, 24.4 percent of all closed charter schools in the state of Michigan were located in the Detroit. Regionally, 42 percent of all charter schools in the state were located in Southeastern Michigan during the 2013-14 academic year, while 57.1 percent of the closed charter schools were from the region.

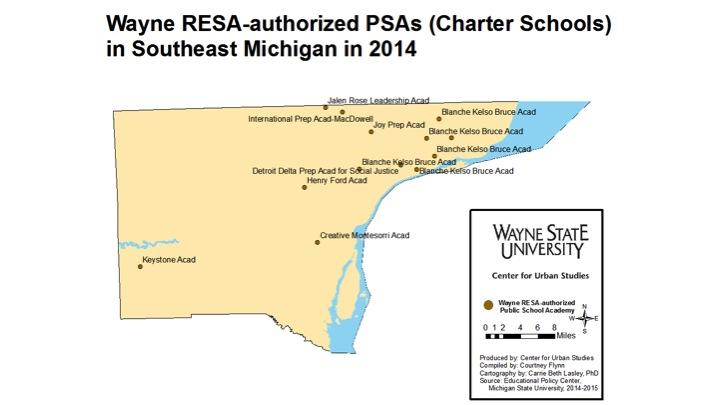

Just as the city of Detroit had the highest concentration of charter schools during the 2013-14 school year, it also had the highest number of closed charter schools at 28. Of the closed charter schools, Central Michigan University was the largest authorizer with 13 of its charter schools being shuttered in Southeastern Michigan for the 2013-14 school year. When looking at authorizers for just the city of Detroit though, Wayne RESA had the largest number of closed charters at 8. The reasons charter schools close ranges from lack of financial stability and enrollment to poor academics. For example, following the 2013-14 school year the closure of the Catherine Ferguson Academy, authorized by Wayne RESA, made headlines (add MI Public Radio link) because the academy, as the city’s dedicated high school to pregnant teens and moms, was closing because of lack of enrollment and funding. When examining a document produced by the state of Michigan listing all closed charters in the state, other reasons for charter schools closing include: poor academics, reorganization, lack of governance, leadership viability, the contract not being renewed, or the authority of an authorizer being revoked.

Despite charter schools closing for a variety of reasons, the 2014 Detroit Free Press report on charter schools shows that many authorizers leave poor performing schools open for a number of years. The focus of the DFP’s particular report was on schools authorized by Central Michigan University, and it highlighted how during a spot check of seven different charter schools during the 2012-13 academic year five were reauthorized despite a history of poor academic progress.

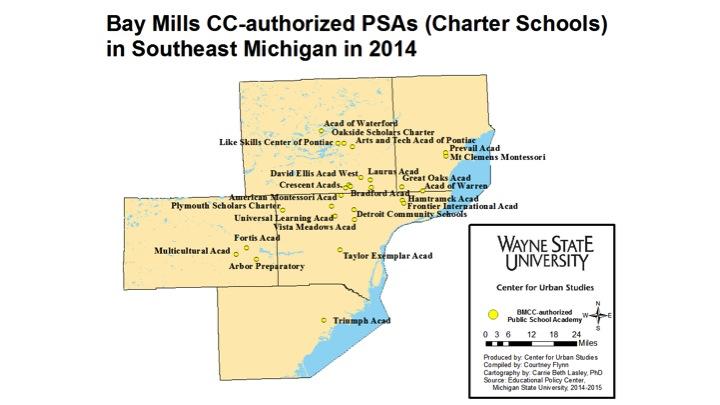

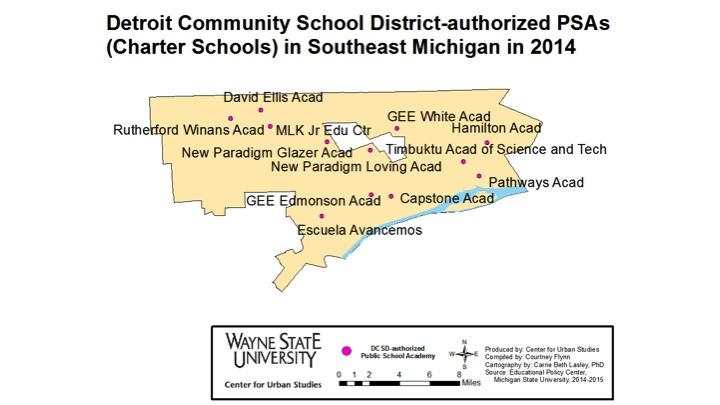

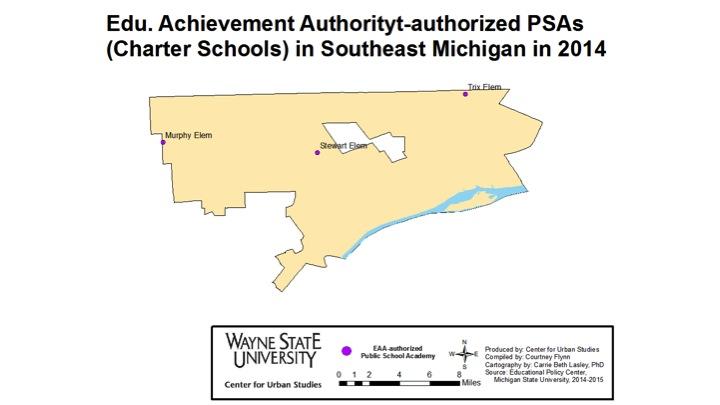

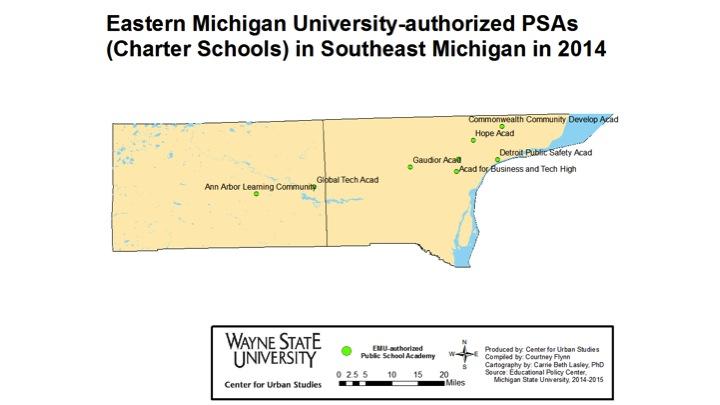

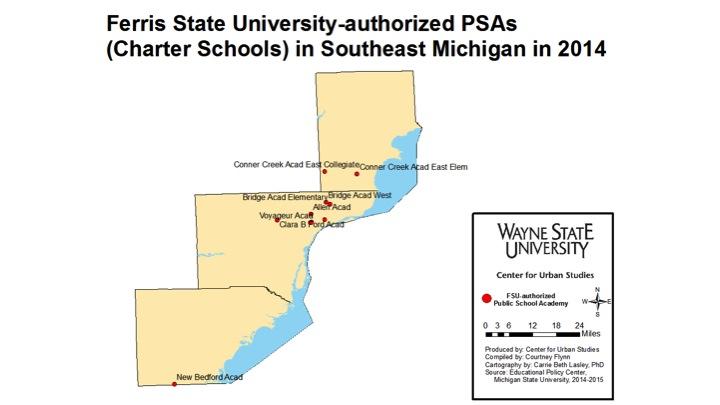

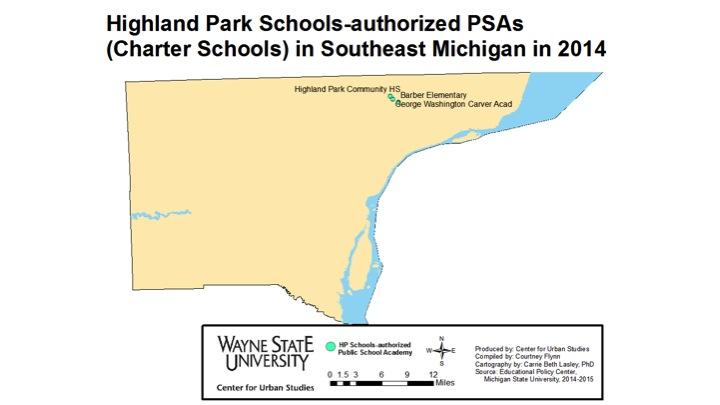

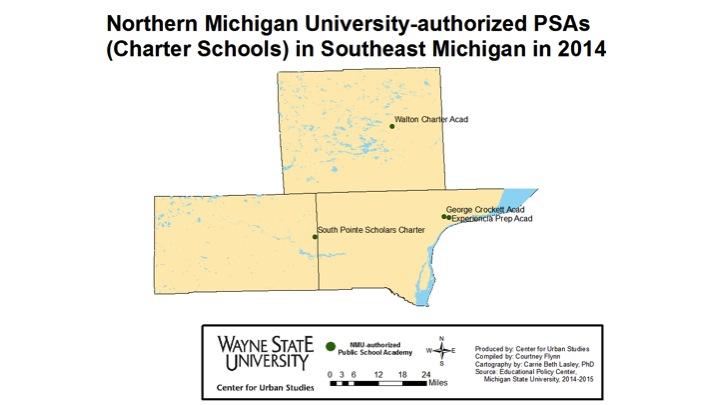

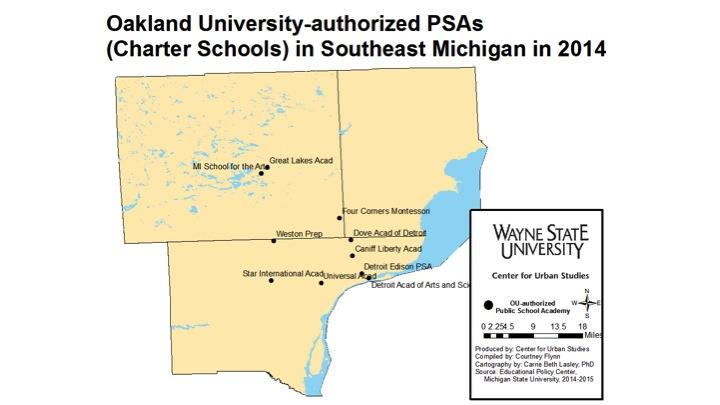

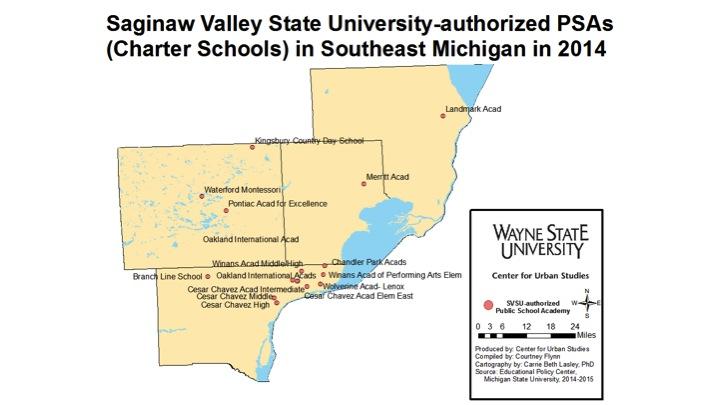

Below are individual maps for each charter school authorizer in the state that had schools operating during the 2013-14 academic year in Southeastern Michigan. As noted early on in this post, majority of the charter schools in the region were concentrated in Detroit, with Grand Valley State University being the largest authorizer in the Detroit.

Central Michigan University was the largest authorizer regionally, and throughout the state. Charter schools authorized by regional education services authorities (Wayne County) , an intermediate school district (Macomb and Washtenaw counties) or a city based educational authority (Highland Park, Detroit) remain only in that particular county/municipality. The charter schools authorized by public universities and community colleges, however, can stretch across counties.

Charter schools were created as a means to provide additional educational choices to students. While the number of charter schools has increasingly grown throughout the state of Michigan and regionally (particularly after the cap for the number of charter schools a university can authorize was removed in 2011) the question on what type of choice these charter schools bring remains. Throughout this post we already saw schools are both shut down and kept open, despite poor academic performances. The Detroit Free Press series referenced in this post discusses charter schools’ lack of accountability, despite the fact they use public dollars to operate. Next week, we will look into the academic performances of Southeastern Michigan’s charter school authorizers and how these performances are associated with certain socioeconomic backgrounds.