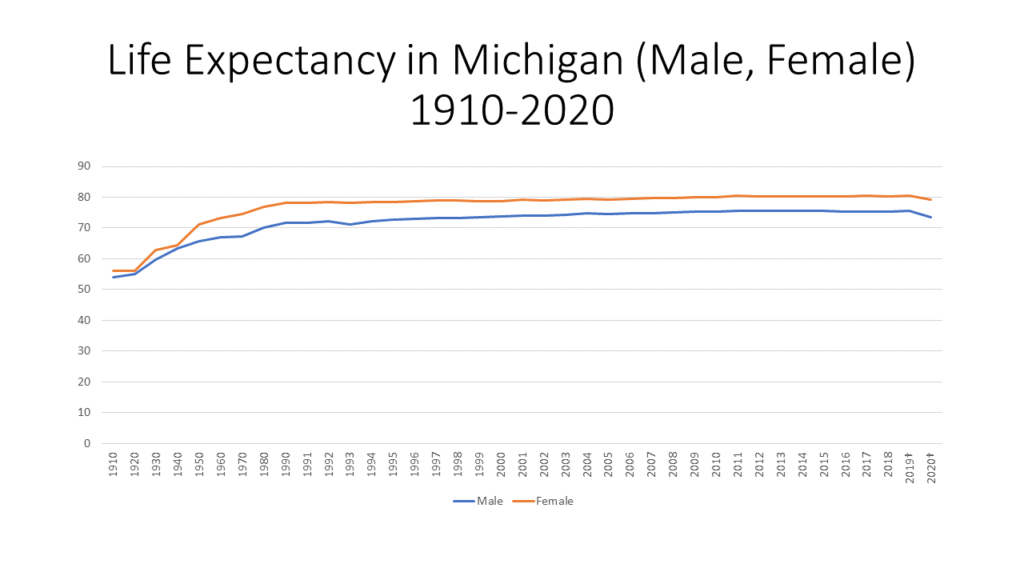

The average life expectancy for Americans decreased in 2020, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, and the same goes for Michiganders.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, which is run by the Centers for Disease Control, the average life expectancy of an American in 2019 was 79 years of age and by 2020 that decreased 77 years of age. In 2021, the National Center for Health Statistics reported the average life expectancy of an American decreased to 76 years of age. For Michigan, the Michigan Department of Community Health did not have data for 2021, but for 2020 the average life expectancy of males and females, both white and black, declined.

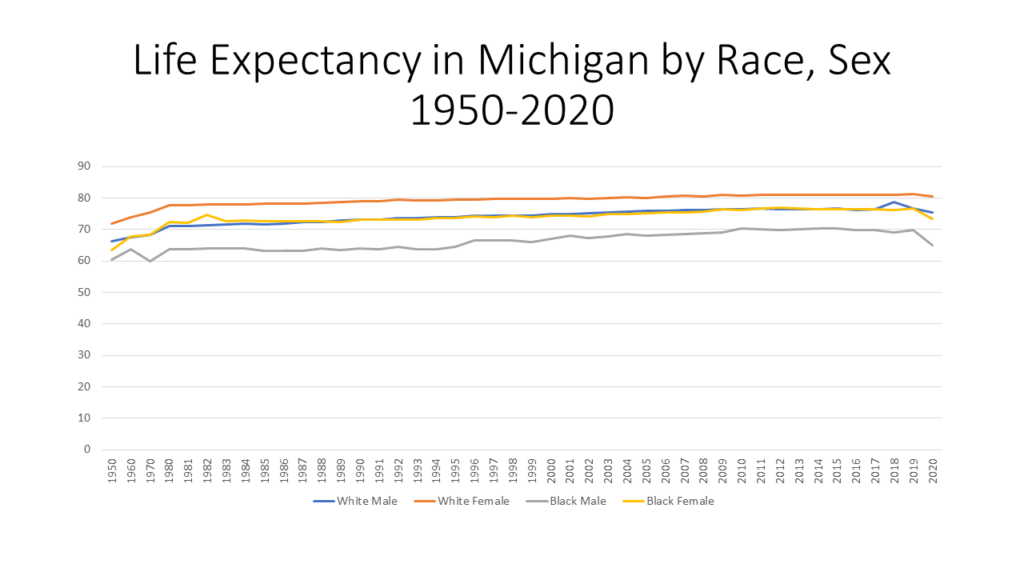

The first chart below shows that between 2019 and 2020 the life expectancy for females declined from 80.6 years of age to 79.2; for males the average life expectancy declined from 75.7 years of age to 73.6. Prior to the reported 2022 average life expectancy ages, the last times they were as low was in 2002 for females (79 years of age) and 1999 for males (73.4 years of age).

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the top 10 contributing factors to death for those who live in Michigan in 2020 were:

•Heart Disease (117,087 deaths)

•Cancer (21,118)

•COVID-19 (11,362)

•Accidents (6,044)

•Stroke (5,873)

•Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (5,644)

•Alzheimer’s Disease (4,860)

•Diabetes (3,408)

•Kidney Disease (1,940)

•And Influenza, Pneumonia (1,880)

So, while the numbers above help frame the story as to why Michigan’s average life expectancy is decreasing, digging into the data another way also tells another story.

The Michigan Department of Community Health publicly presents data on the average life expectancy broken down by both sex and race. As shown above, overall, females have long had a higher life expectancy over males. However, when further breaking down the data, we see that black females and white males in Michigan have had nearly the same life expectancy since 1910. In 2020, the average life expectancy for black females in Michigan was 73.3 years of age, a decrease of 3.3 years from 2019. The average life expectancy of white men in Michigan was 75.3 years of age in 2020, a decrease of 1.3 years from 2019. White females in Michigan experienced a 0.9 decrease in average life expectancy, which was the smallest decrease of the four groups. It was black males who had the largest decrease in life expectancy between 2019 and 2020 in Michigan at 4.8 years; in 2020 the average life expectancy for black males in Michigan was reported at 64.9 years of age. The last time the average life expectancy for black males was that low, or lower, was in 1995 when it was reported to be 64.4 years of age.

According to the Michigan Department of Community Health, the top leading causes of death for black males in Michigan in 2020 were:

•Heart Disease (2,430 deaths)

•COVID-19 (1,610)

•Malignant neoplasms (1,272)

•Accidents (799)

•Assault ( 512)

Note that assault is not even among the overall the top 10 causes for Michigan citizens overall.

Overall, decline in life expectancy for all sexes and races is concerning as it means people are dying earlier than they should be.