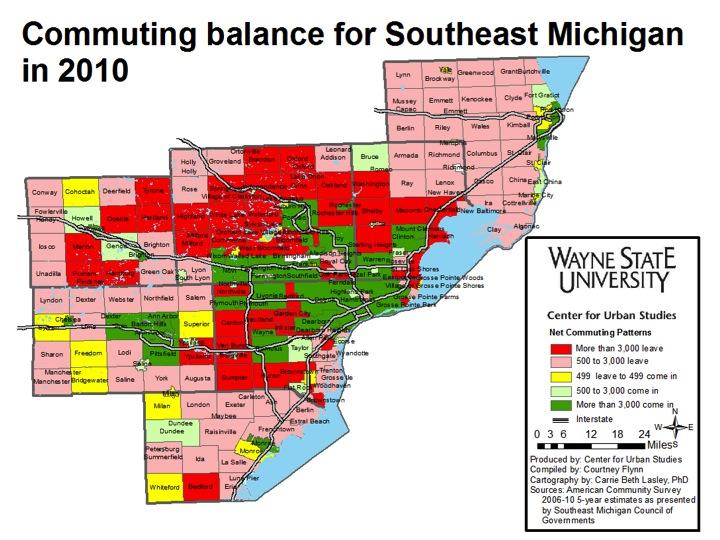

This post examines work-related, commuting patterns for Southeastern Michigan. In 2010, the majority of the commuting within the region was either to or from the city of Detroit or the area directly around it. Interestingly, 228,000 commuters left the city of Detroit each work day to work in another jurisdiction, but at the same time, 277,000 commuters from the suburbs also traveled to the city to work, according to data provided by the Southeastern Michigan Council of Governments and the American Community Survey. A deeper dive into the data shows that the city of Southfield received the highest number of commuters (12,600) from Detroit, but it also sent the highest number of commuters to Detroit (8,800).

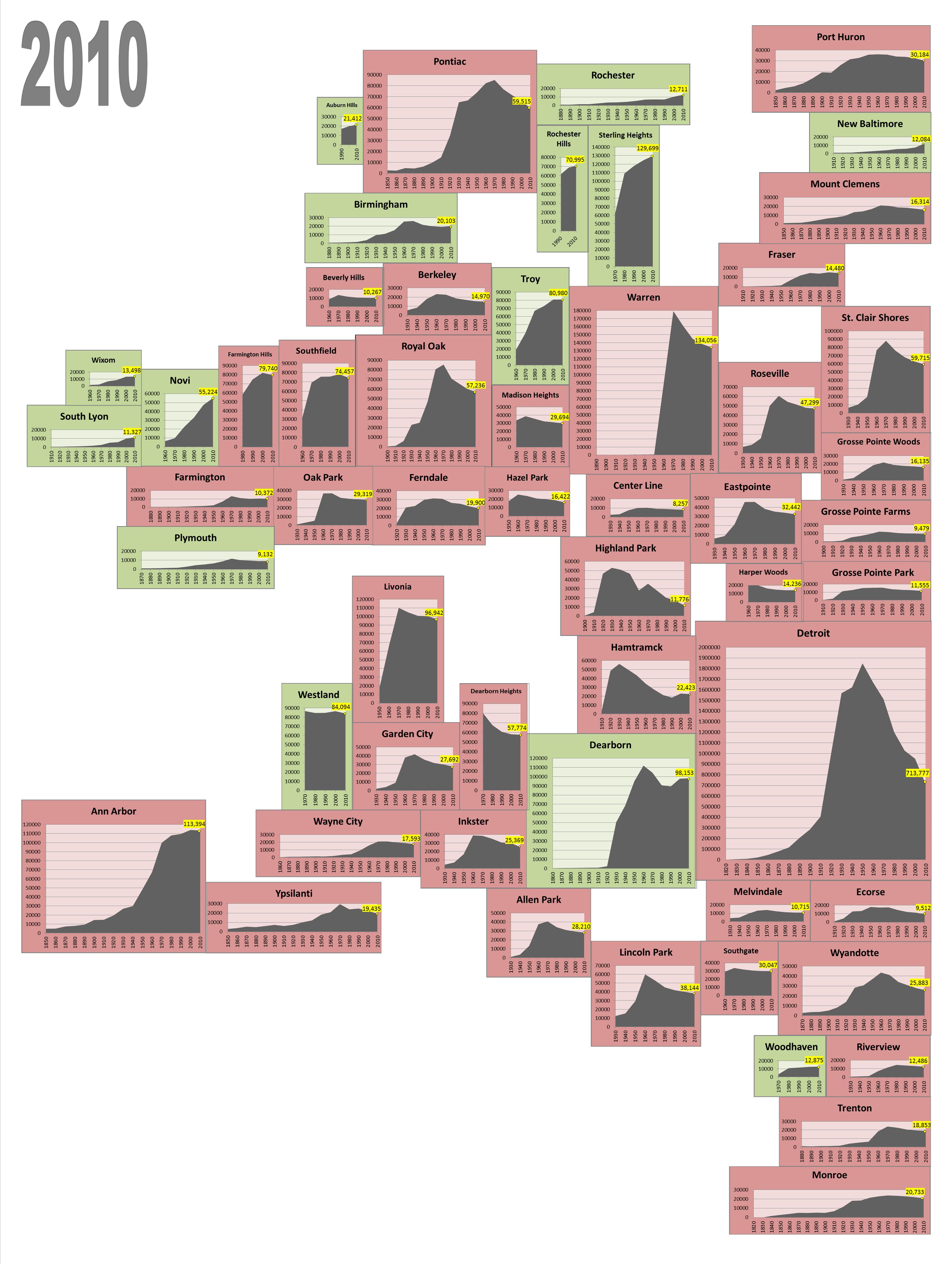

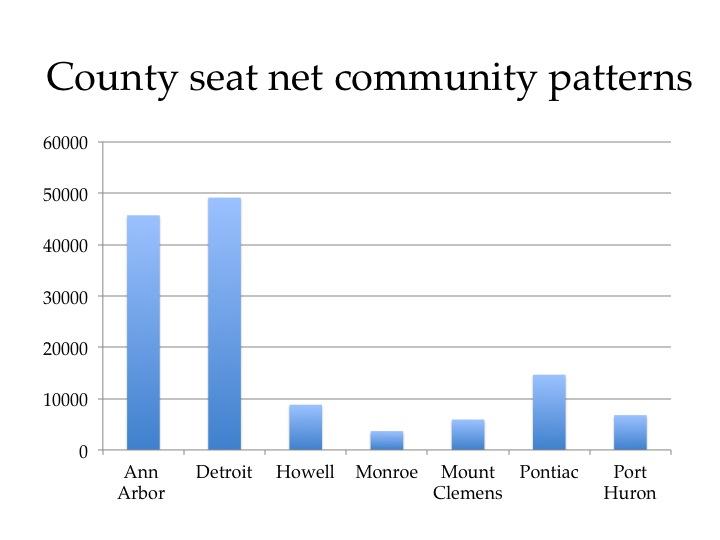

The above map shows the net commuting patterns for the region in 2010 and we see that the county seats in each county (Howell, Mount Clemens, Pontiac, Port Huron, Ann Arbor, Detroit and Monroe) all have net positive commuting patterns of more than 3,000. This means that more individuals are coming into that that city than leaving.

A few of the inner ring suburbs of Detroit, like Dearborn, Warren, and Southfield also have net positive commuting patterns of more than 3,000 commuters, along with other communities like Troy, Romulus (which is where the Detroit Metropolitan Airport is located), Livonia, and Novi.

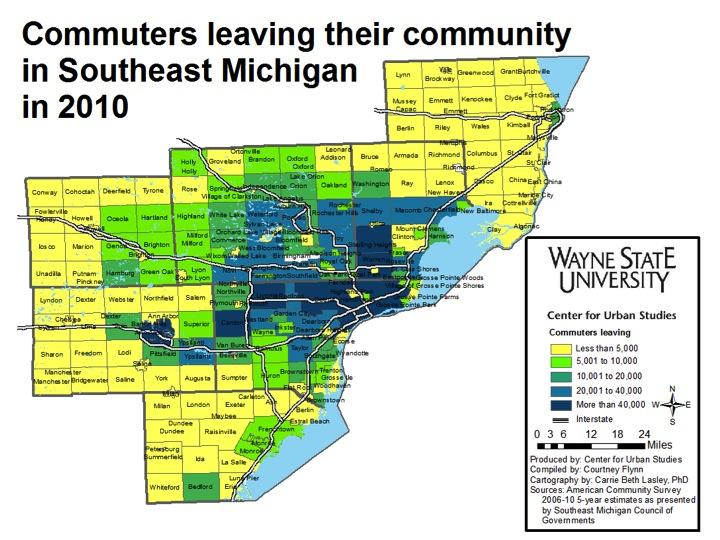

On the other side of the spectrum, we see that there are about two dozen communities where 3,000 or more commuters leave their place of residence to commute elsewhere (a net negative). Particularly in Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties, we see that the communities with a higher loss of commuters surrounds the communities that receive upwards of 3,000 daily commuters.

In addition to the dark red signifying the loss of 3,000 or more commuters a day, the lighter red shows that the more rural outskirts of the region (which are also less populated) tend to lose between 500 and 3,000 commuters a day. This shows that, overall, a majority of the communities within the Southeast Michigan region are losing commuters, rather than gaining them.

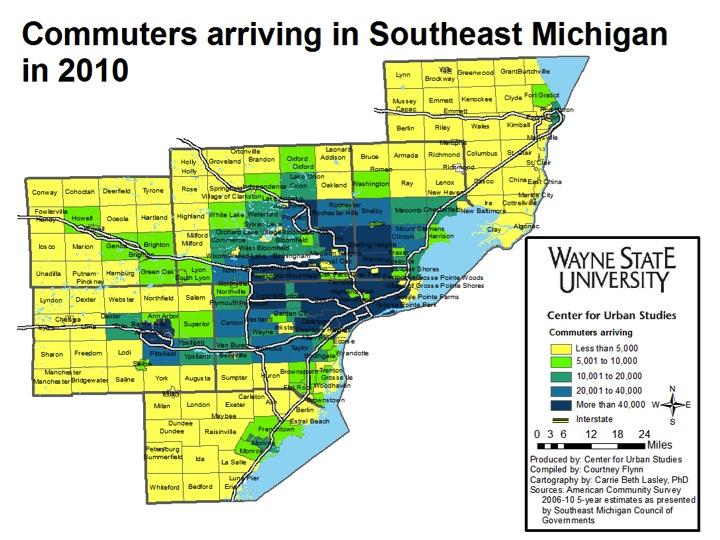

As already noted, in 2010, a large number of motorists from the region commuted to Detroit each day for work. From the first map, we know that the city gained more commuters than it lost. The second map shows it received substantially more than 40,000 commuters each work day (277,145 total). Other Detroit suburbs that received 40,000 or more commuters are Southfield (82,643), Sterling Heights (55,097), Warren (82,442), Troy (87,193), Livonia (72,663), and Dearborn (83,005). But, as noted in the map below, Sterling Heights also loses more than 40,000 commuters (58,998), which is why their net commuting pattern shows a loss in the first map (net loss of about 4,000).

Additionally, in looking at all three of the above maps, we see that the communities that tend to gain and/or lose the most are located around the interstates. For example, in following I-96 out of Novi through Livingston County we see that communities like Genoa, Green Oak, and Lyon Township both gained and lost between 500 and 3,000 commuters.

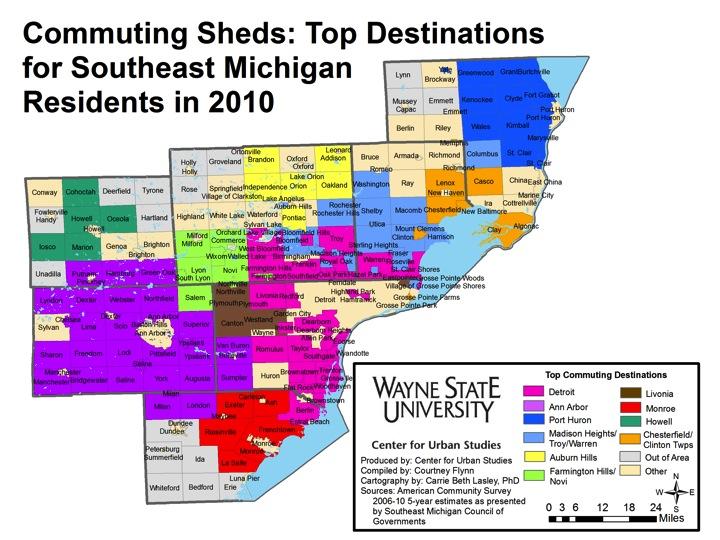

The above map shows the top commuting destination for each community. For example, all of the Downriver area and most of the inner-ring suburbs have a majority of their residents commuting to Detroit for work. However, in Washtenaw County, a the majority of the residents commute to Ann Arbor, and in St. Clair County, most of the commuters who live within the county travel to Port Huron. These patterns again reflect that county seats tend to be a common destination for those commuting to work.