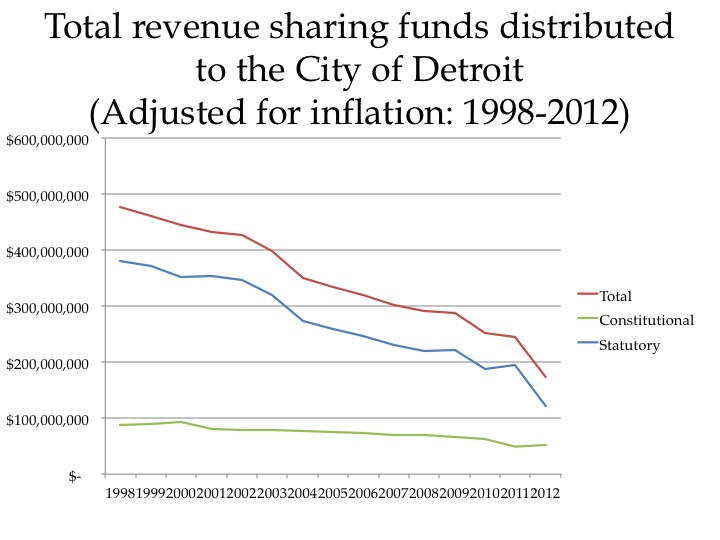

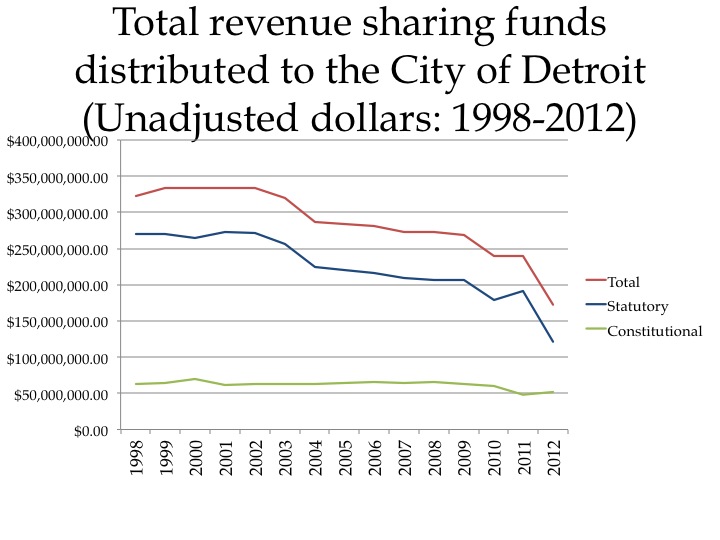

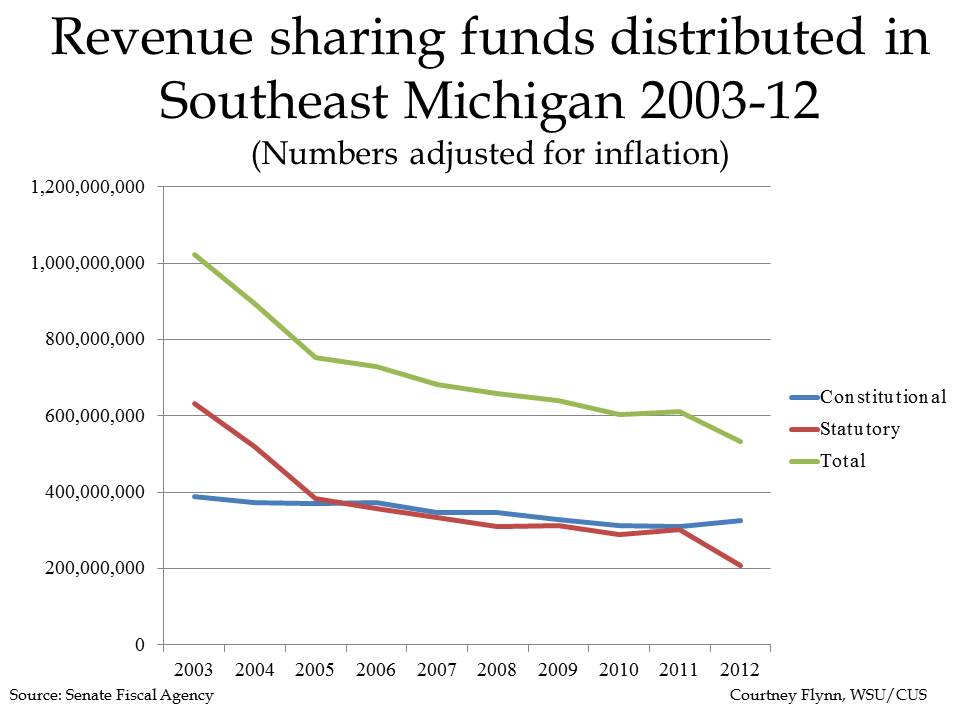

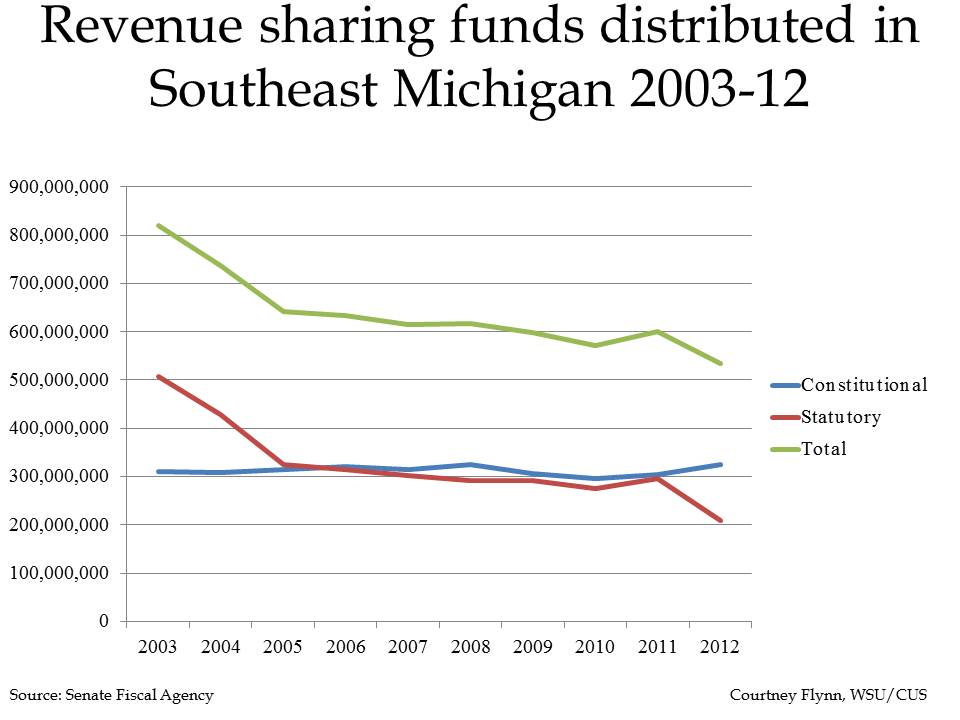

In this post, we provide examples of two communities’ constitutional and statutory revenue sharing allocations over time. The first community is Detroit, which saw a 56.8 percent decline in total revenue sharing from FY 2002 to FY 2012, adjusted for inflation. The second community is Macomb Township, which was one of just 13 communities–and an illustrative example–to see an increase in its total revenue sharing payment (14.5 percent). While Macomb Township has experienced a population increase, the city of Detroit has experienced a decrease. We examine these communities’ revenue sharing allocations for five fiscal years: 2002, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2012. For a look at the total change between 2002 and 2012, look at our previous post.

We noted in our preceding post that Michigan provides two types of revenue-sharing payments to its local governments: constitutional and statutory. Constitutional revenue sharing is authorized and defined in the state constitution while statutory revenue sharing is authorized by legislative statute. A key difference between these two sources is their susceptibility to change. Only constitutional amendments can change constitutional revenue-sharing formulas, whereas the state legislature can alter statutory revenue-sharing formulas at any time.

Constitutional Revenue Sharing

The chart below shows the calculation of Detroit and Macomb Township’s constitutional revenue-sharing payments for the five selected fiscal years during the 2002-2012 decade.

This chart illustrates the two primary components of Michigan’s constitutional revenue sharing: residential population and the constitutional distribution rate. The state determines the constitutional rate using 15 percent of gross 4-percent sales-tax collections (The other 2 percent of Michigan’s gross sales-tax collections are designated for educational purposes.). As described in a previous post, this means 15 percent of state sales tax revenue will be distributed to Michigan’s municipalities. Lower gross sales tax collections from FY 2002 from FY 2009 caused a decline in Detroit’s constitutional revenue sharing during that period. However the decline, initially due to lower gross sales tax collections (FY 2002 – FY 2009,) preceded the much steeper decline in FY 2012 due to considerable population decline reported in the 2010 Census.

The chart above also shows that Macomb Township experienced similar declines due to lower constitutional rates. But unlike Detroit, Macomb Township’s FY 2012 constitutional revenue sharing payment was much higher (57.9 percent) than its FY 2009 payment, due to its population growth reported in the 2010 Census. Despite the differences between the two communities, these constitutional payments changed from year to year because of population and economic changes, rather than policy changes.

The constitutional distribution rates are estimates based on dividing the total constitutional payment by the population. For FY 2009, it is not mathematically possible for the distribution rate to be the same for Detroit and Macomb Township given their population and reported payments, which is why they are calculated estimates.

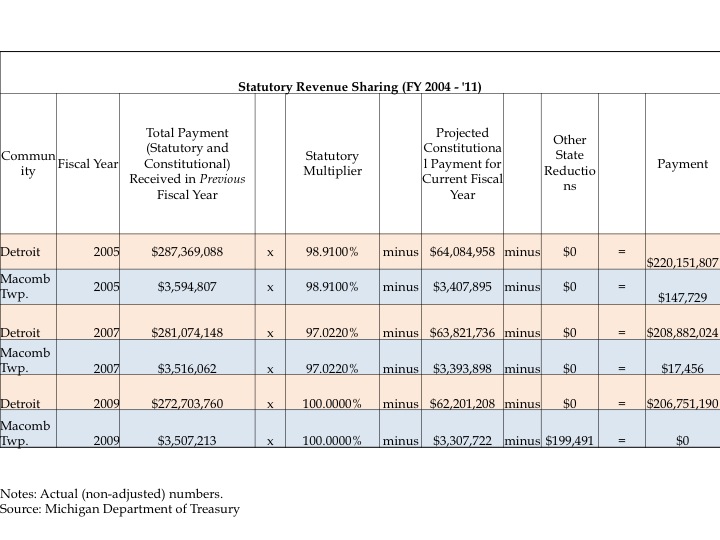

Statutory Revenue Sharing

Unlike Michigan’s constitutional revenue sharing, statutory revenue sharing formulas are subject to regular legislative modification. As we described in our last post, the Michigan Legislature outlined a complex set of criteria to determine statutory revenue-sharing payments through 1998 PA 532. The chart below shows how these formulas were used to determine Detroit and Macomb Township’s statutory payment in FY 2002.

The chart reveals that Detroit’s FY 2002 statutory revenue sharing payment came exclusively from the “Percent Share of FY 98” component of the FY 1998 funding formula. Macomb Township received its greatest statutory funding allotment under the weighted population factor distribution. Neither community received statutory funding under the “yield equalization” component.

According to the Michigan Municipal League, the 1998 formulas were not fully implemented due to statewide budget cuts. The House Fiscal Agency notes that the legislature made various statutory changes that superseded the 1998 formulas before they officially expired in 2007. Key examples of these changes include statutes 2004 PA 355, 2005 PA 196, 2006 PA 437, 2007 PA 127, and 2008 PA 261; each of which prevented the respective fiscal year’s total revenue-sharing payment from exceeding the previous fiscal year’s total payment. Furthermore, Statute 2004 PA 356 suspended revenue-sharing payments to counties. According to the Michigan Department of Treasury, these changes required new allocation formulas for much of the period spanning FY 2004 and FY 2011. Examples of these calculations for Detroit and Macomb Township, for three selected fiscal years, are shown below.

The chart above shows two key components of the new allocation formulas: the previous fiscal year’s total revenue sharing payment (including the constitutional payment,) and the statutory multiplier. Since most statutory language during this time prevented a statutory payment increase, communities whose statutory payments declined to zero were not eligible for a statutory payment the following year. This was the case for Macomb Township, which did not receive a statutory payment in FY 2008 and therefore received no payment in FY 2009. The chart reveals that this requirement resulted in an effective loss of $199,491 in statutory payments for the township, as it would have received that amount otherwise. Also, although not reflected in these charts, it is worth noting that Executive Orders 2002-22 and 2009-22 further reduced FY 2003 and FY 2010 statutory revenue sharing payments throughout the state.

The most recent change to Michigan’s statutory revenue sharing formula is the Economic Vitality Initiative Program (EVIP). Promulgated in Public Act 63 of 2011, EVIP replaced statutory revenue sharing and required eligible recipients to comply with certain requirements. According to MDT, local governments that received more than $4,500 in statutory revenue sharing payments in FY 2010 become eligible for EVIP payments. Eligible units were required to submit evidence and documentation for meeting designated requirements in the realms of: (1) accountability and transparency, (2) consolidation of services, and (3) employee compensation. Each category represents one third of the total EVIP amount available, and it is possible for a local government to receive some funds for just meeting one or two EVIP category requirements The FY 2012 EVIP payments for Detroit and Macomb Township are shown below.

The chart illustrates how the total amount available is calculated by multiplying the FY 2010 statutory payment by the fiscal year’s statutory EVIP distribution rate. In FY 2012, Detroit met all three EVIP categories and received the full EVIP payment. Macomb Township received no EVIP payments because it received no statutory payment in FY 2010, rendering it ineligible. According to the MDT, EVIP’s enabling legislation ties EVIP eligibility to FY 2010 statutory payments. This means communities like Macomb Township that did not receive a statutory payment in FY 2010 will continue to be ineligible for EVIP unless changes are made to the current legislation.

As a result of a general decline in property taxes and of these changes in revenue sharing, especially in statutory revenue sharing, many municipalities in Michigan are cutting essential services and operating with budget deficits. The state government itself is, however, operating with a surplus. In other states, where local governments are given more latitude in adopting and adjusting local taxes, the fiscal challenges of local cities are often resolved by local increases in sales or other taxes. Given Michigan’s approach of limiting local taxes, municipal governments can do little other than cut back to resolve the revenue shortfalls resulting from declines in property taxes and state action to cut revenue sharing. This, in effect, enforces a fiscal austerity regime analogous to those enforced by international institutions on some countries such as Greece. Politically, it reinforces the classic doctrine that local governments are “creatures of the state,” as opposed to operating in a context “home rule.” State action has, in effect, forced a class of cities into the equivalence of bankruptcy.